Appreciate The Value Of Failure

All good plans fail. But not all failed plans are good. Or, more precisely, all good plans have parts that fail. If a planner has never created a plan in which part of all of the plan failed, they need help – they are either delusional, in that they believe every part of the plan was a success, or their plans were so superficial that they are insignificant.

I have personally experienced all of the failures noted in these essays. Some resulted directly from my actions but many more resulted from the actions of others and from unpredictable events. It does not matter how we feel about the failure, but it does matter if anything was learned that could help avoid such failures in future.

When failures occur, we must learn why. By “what degree” did the plan fail? How can the failure be avoided for the next plan? In fact, a plan in which nothing fails is probably a bad plan because the plan does not aim high enough, far enough, or long enough. This is like students who are so concerned about getting all “A’s” they never take a hard course or a course in which they genuinely know nothing about the subject. Accordingly, as a senior faculty member, when I reviewed student transcripts for program admissions and scholarships, I always looked for a student who got lots of A’a and 1 or 2 F’s.

City planners do not plan to fail. Yet their plans may fail in the sense that the plan leads to poor or even negative results. We can spot the failures by looking at the actual outcomes. Sometimes it takes a few years to actually understand how a plan impacted a community. Evaluation of the plan outcomes may come from outsiders and professional critics. Jane Jacob’s, for example, provided valid and insightful analyses of planning failures in the “Death and Life of Great American Cities”. Her observations ring true after half a century.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s hero, Sherlock Holmes, says, “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” Perhaps professional planners might consider a comparable admonition that when you have eliminated all the roads to failure, whatever decision pathways remain, however improbable, might be successful.

Since my first professional planning work in 1968 I have probably been involved as a decision-maker in 500 projects — as a leader, colleague or subordinate. I have worked for every level of government, for the private sector and non-profit, for wealthy communities and poor. This set of essays discusses many of the planning problems which, based on my field experience, have failed in part. This line of investigation does not come from any theory or belief system – just work. Conclusions based on this line of critical thinking do not always lead to pragmatic planning solutions but do provide a productive place to avoid failure and hopefully find some success.

These essays begin with accepting that there are failed outcomes and then exploring the dynamics of the problem solving process from the viewpoint of the planner. If our plans led to a good outcome do, we still need to evaluate the process or just copy it again? If the results were poor what went wrong – a weakness in our work, an outside event that we could not avoid? Were the outcomes, good or bad? Were good outcomes just the result of luck?

This 2007 plan for Josey Heights in Milwaukee failed. It was a good plan – it fit into the neighborhood, it provided affordable housing, it uses design concepts for the homes and the facades that were visually appealing. It failed at that time because the market evaporated due to the Great Recession. For me, it is a simple lesson – good plans use long-term concepts which fail because we cannot foresee long term trends and assume short term conditions will last. Today, almost 20 years later some homes have been built. Did the long-term plan fail or just the short-term plan?

Planners should understand all the challenges to their plans – all the things that have to go right, all the pitfalls and barriers to great outcomes. Then they must try to overcome those challenges. It is the “trying” that separates strong plans from weak ones. The essays in this section reflect on almost all of the types of barriers we encounter as professional planners and how we can try not to fail.

In 1967, during my first month of graduate school at Cornell, Barclay Jones (our professor later mentor to many of my fellow doctoral students) opined to the class that in the field of medicine, prior to the discovery of penicillin, a sick person who heeded the advice of a physician had better than a 50% chance of a negative outcome. Yikes! The patient would have a better chance of improvement by not seeking professional medical advice. After the invention of penicillin, Professor Jones claimed, the odds of improvement for the patient rose above 50%. In his opinion, however, the planning profession had yet to reach a 50% benchmark for professional success in decision-making. Today, half a century later, I suspect the planning profession has passed that 50% milestone but not by a lot.

Can we discern clear differences between plans that succeed and those that fail? How do we make such judgments for long term problem solving? Do you know of plans that seemed to fail for a few years and then succeeded? Or do you know the opposite pattern – plans that succeed and then fail? Just saying “let’s do our best” is no comfort to future generations if the “best” has been the “worst”.

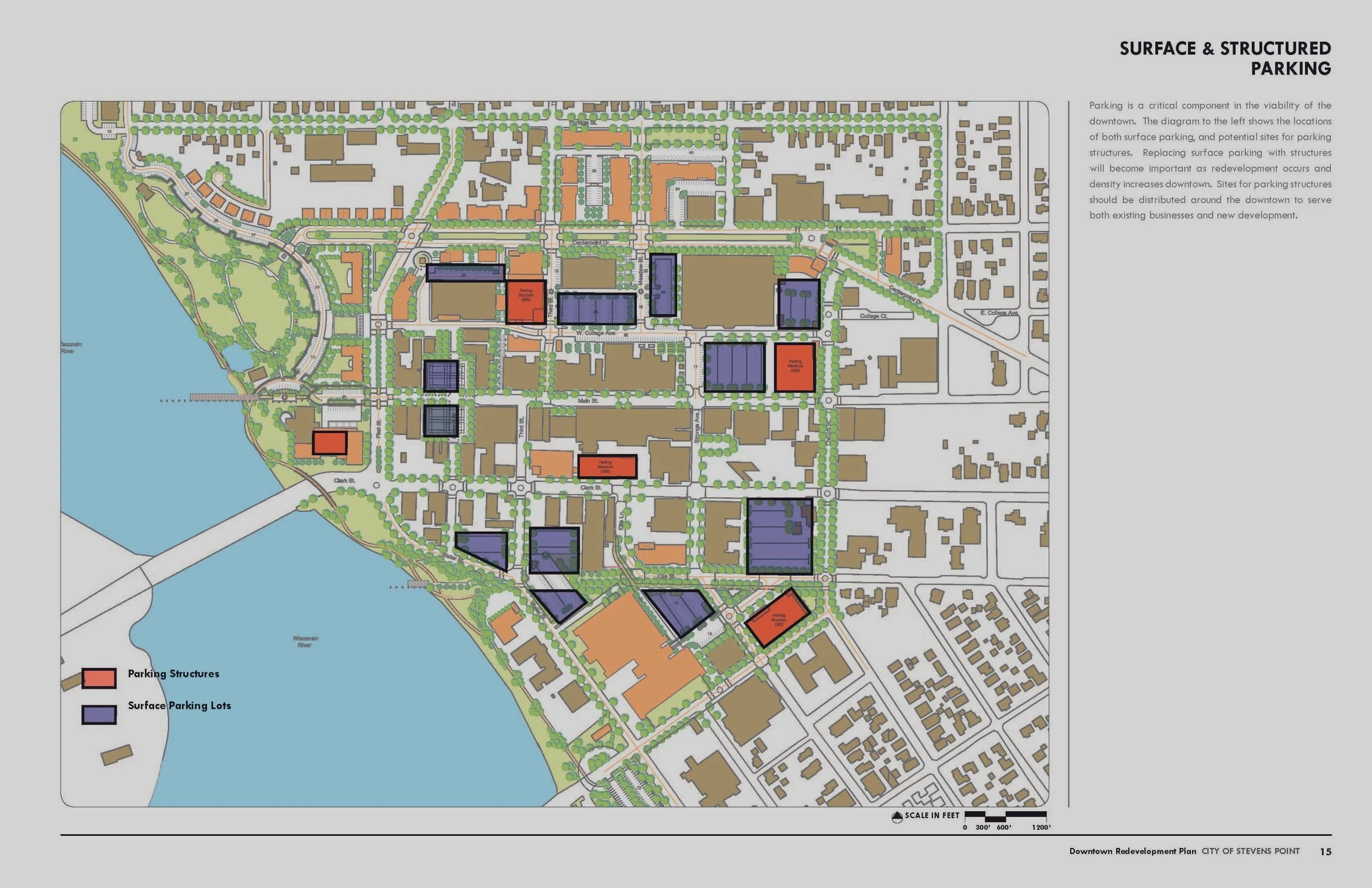

How do we define success and failure? All four of these plans failed , completely or in part. The top two plans were not built. (a) The plan on the upper left was a concept for Pabst Farms in Oconomowoc that was proposed to replace an approved plan. This proposal doubled the density, doubled the open space, and cut infrastructure in half, but it was not in keeping with market projections of the developer. Today, half the land sits vacant. (b) The plan on the upper right received full approval from the community and the developer but, like other concepts, fell victim to the Great Recession. Later, as the community leadership changed the plan was disregarded. The bottom two plans achieved partial success. (c) The lower left plan for downtown Stevens Point was used for some changes but not all. Some, but not all ideas, were implemented. (d) The lower right plan for the City of West Bend proposed for our developer/client was rejected. A few years later, the infrastructure of roads and public places was actually implemented and opened up the River to public use and a new museum. Three planning efforts later we were rehired to add additional improvements which are being implemented. The plan details failed but the impetus for change remained, and good outcomes were achieved.

Find Wisdom (and Foolishness) in Places & Traditions

Until I wrote this essay, I did not realize that many of the lessons I learned about the failure of planning probably started when, as a young boy, I read folk tales about the “Wise People of Chelm”. These stories go back 2 or 3 centuries in Yiddish, Polish and German culture, long before there was an American Planning Association, professional licensure, zoning, comprehensive plans, and numerous other specializations in economics, politics and design. There is, in fact, a real City of Chelm whose growth and development has little to do with these folk stories.

The folk tales regarding the foolish decisions made by fictitious leaders of Chelm have gained validity. These humorous outcomes do not represent the decisions of just one small village but communities around the world. These stories, like many that last for centuries, reveal common truths. As these fictitious decision makers act foolishly, they always convince themselves of their wisdom, collective insight, forward thinking, and uncanny ability to find ways to fail again forever.

Do the Chelmites ever blame themselves for anything which has gone wrong? No! “It’s just that foolish things are always happening to us.”

I have always remembered one story where the Villagers wished to build a water mill as a symbol of their community’s wisdom and foresight (in economic development). They also realized that such a functional facility should also become a destination symbol – a true landmark of a forward-looking community. They would place the water mill atop the biggest hill where it would be visible for miles to all who visited the town and a reminder to all who lived there of the prowess of local leaders. The absence of the river needed to turn the water wheel was mentioned only by the town fool known as Gimpel who, the leaders knew, just did not “get it.” His passive attempt to suggest a location by the river was ignored. Instead, the community solved the problem brilliantly by carrying buckets of water to the top of the hill to run the water wheel. The solution not only failed, but it also got worse as they tried to remediate the situation. This story has all the earmarks of many of our planning attempts including the planner as fool.

You can discover how the Chelmites parlayed this initial, but unacknowledged foolishness, into an interminable series of bigger errors: the community followed the wrong leaders: found bad solutions at the outset"; adopted the wrong mission; followed the wrong beliefs and theories; used misguided methods; designed the wrong places; worked without talent; misused their resources; and, at the end, were convinced they acted appropriately. Does this sound familiar? It should. If it does not sound familiar you have to think again.

The foolishness of Chelm’s leaders comes from broad cultural traditions. When writing this essay I began to look back at what I had read about Chelm as a youth. I never imagined I would see it as a cautionary tale applicable to my chosen profession. Many volumes have been written about the traditions underlying the humor of foolishness. Yet Chelm today bears little resemblance to these stories. Chelm is a real city that has sustained itself for more than a millennium under the rule of many regimes — some good and some evil. Ruth Von Bernuth’s book entitled “How the Wise Men Got to Chelm: The Life and Times of a Yiddish Folk Tradition” offers a superb lesson on the history of discussing foolishness as a way to think about wisdom.

Several years ago I read another account about the first years of activity in Celebration Florida. This new town came with many planners and Disney’s Imagineers. The Plan included a walkable main street that did not, at one time, have enough business because the population was too low. So, they bussed in tourists in proverbial buckets from Disneyland.

Find “Right” Clients & “Right” Places

For decades planning schools have taught their students how to help those segments of society that are poor, disadvantaged, or otherwise at the bottom of the ladder of social stratification. Often these issues become mired in corresponding political or partisan debates about the best way to help persons or groups who fall into these categories.

One view of social stratification views persons at the top of the ladder as a resource to be taxed or regulated for the benefit of those at the other end of the ladder. Both sides of the political spectrum show evidence of this view and vary only in the degree. That is, no one argues that the rich should pay nothing, but they always argue about how much. However, as the debate continues, our cities become increasingly segregated.

There is another view of stratification, probably less popular, which I first understood in an essay by J.B. Jackson in which he described the public life of the baroque city. In his description he notes that most baroque cities had an extremely rich, diverse, and exuberant public realm because rich and poor mixed freely in the street and public places. There was little need to segregate society geographically in order to distinguish social class because it was self-evident as to who the prince was and who was the pauper. In that culture, spatial segregation was diminished because other cultural conditions helped people express their relative social standing.

These illustrations all come from the creation of the Luxembourg-American Cultural Center (LACC) in Belgium, Wisconsin. The ideas underling this project came from multiple sources including historical architecture and development in Luxembourg from prior centuries, current economic and social conditions in Wisconsin, and numerous planners, designers, and cultural leaders. This is an excellent example of how plans, when implemented, encounter circumstances in which some ideas are implemented, and others must be set aside. The LACC today is thriving and growing. The overall intent and mission were a great success while the details were adjusted as needed during implementation.

Today, most planners do not want to encourage that type of class system. However, it might be useful to look at some of the attributes of Jackson’s view of the baroque city which could be used in a positive way – not unlike the process of extracting useful medical materials from venomous snakes or poisonous plants. Put simply, it seems that the more clearly, we can avoid the need for geographic segregation as a means to represent social status, the more we can begin to create the social diversity within places (not between them) that brings people together from different social strata.

This approach requires a different way of looking at wealth and those who possess wealth. Rather than view such persons as targets for taxes or regulations (regardless of partisan politics) we can view such persons as people who can implement the types of communities we want. This is not a call to remove greater taxation of people with wealth, but rather to add another planning tool of creating programs and incentives that leverage wealth for mutual benefit of both those that have it and those that do not.

J.B. Jackson also notes that in earlier centuries – during feudal periods – person with wealth often felt a responsibility to the communities over which they ruled and created resources for the common good of such communities. He notes further that today corporations that have replaced feudal lords. However, many corporations create “autonomous” places that do not benefit the local public but, instead, become highly neutral, inauthentic places (think of the shopping malls that were created in identical fashion across multiple regions and nations). Two notable exceptions that illustrate the rule of customizing corporate places to local culture are Rockefeller Center and Paley Plaza – both wonderful public places, near each other, created by organizations and people with wealth that would never have been created otherwise. Were these “right” places made by the “right” clients?

Within this myriad of belief systems and conventional practices we still need a direction to follow. If planners should not pursue a perfect city, but at least make it better, we still need a clearer sense of our mission.

Here are four examples of different patterns of success and failure. The three plans at the top were all implemented, in part, but with different details – the North End housing development (upper left) along the Park East corridor in (Milwaukee), the larger area plan (top row center) for the Luxembourg American Cultural Center (Belgium, WI), and the river edge housing and commercial development (upper right, (Milwaukee). The bottom plan, displaying multiple land uses in a Comprehensive plan for Glenview Illinois was not followed in any detail, but the concepts that were not used in that project have been implemented successfully in many other projects. The point is that planning, as a process, creates a sequence of successes and failure. The professional lesson is to follow that sequence as it unfolds.