Make Useful Documents

The Plan As A Document

Over the decades several types of planning documents have dominated the planning profession. The names change slightly but the contents stay fairly constant. For example, the “comprehensive plan” (also called a “master plan” or “general plan”) has been the historic mainstay of American city panning. Equally frequent have been special area plans for downtowns, city centers, campuses, neighborhoods, and major streets and corridors. More recently, but still gaining in frequency, have been special purpose plans for distinct types of use or programs such as park systems, bicycle and pedestrian plans, climate impact and energy plans, and economic development. While these plans have different names there are certain commonalities which new planners entering the profession need to understand. Mel Scott’s book American city Planning since 1890 contains a great analysis and critique of how planning in the U.S.A. began and evolved over time into a robust diverse profession.

Almost all plans become documents. They vary in length, but they all have substantial graphic content. Burnham and Bennett’s Plan of Chicago was much more than a simple document. It was an influential statement that, by force of its thoughtfulness and communication techniques, changed the shape and future of Chicago (and many other cities). A brief look through the history of planning since the 1892 Columbian Exposition will show critical documents created by planners as the basic output of the planning process.

Plan documents vary in terms of organization and emphasis, but they usually contain some common elements:

• An executive summary

• Images, text, and tables of problems and solutions

• Implementation

• Analysis of existing conditions

• Projections of future issues that will impact the community

• Relevant examples from other places and communities

• Acknowledgement of the people and organizations instrumental in creating the plan

Comprehensive (Long Term) Plans

The comprehensive plan (sometimes called a master plan or general plan) has become the most significant concept in American urban planning. Every professional planner should know and understand this type of plan and its variations. The simple idea is that communities should prescribe their desired outcomes for physical, social, economic and environmental future over 10 or more years. Each comprehensive plan will vary in its anticipated length and the emphasis placed on different issues. These plans usually become official, legal documents adopted by elected officials and intended to be used as a template for making decisions. Each community varies in the degree of authority they use to mandate the recommendations of the plan.

In recent decades states and local governments have adopted specific guidelines for the contents of such plans. Initially, in 1962, T. J. Kent’s The Urban General Plan, created a template that many communities and planners adopted. Over time, other templates have emerged from practitioners, state governments, and national organizations. Some states have very strict guidelines in which comprehensive plans are enforced in great detail while other states allow the plans to be used in a flexible manner, even ignoring them completely when short-term political priorities require contradicting the plan.

In some communities the basic organization of the plan follows the structure of administrative departments (such as transportation, parks, utilities, and so forth). This mode of organization is relatively easy to prepare, especially since much of the supporting data often comes from different departments within local government. This second mode of organization – by type of place – may be more difficult but it is usually more useful and easier to understand for the general public and key stakeholders.

The content of comprehensive plans usually includes specific recommendations for dimensions and geography of the critical places, public services, programs and policies. In addition, most comprehensive plans address questions of visual character, preserving local history, preserving or improving environmental quality, maintaining desirable social and economic activities, all modes of circulation, and the long-term operation and sustainability of the community’s infrastructure of services and institutions.

Land use plans can reflect simultaneously both (a) the visual grain and texture of an urban pattern with precise building footprints, streets, rivers, and landscape and (b) the land uses shown in color codes that reflect both single use and multiple-use buildings. Excerpts from the Comprehensive Plan, Glenview, Illinois, 2003.

A never-ending debate surrounds the development and use of comprehensive plans. Some planners believe that the conditions surrounding cities and their future are far too uncertain to support highly specific long term plans. Others suggest that community’s need to establish precise long term visions in order to move in the right direction. Balancing these two viewpoints frames the professional attitude towards long term planning. One way to achieve this balance is to view long-term aspirations as ideas only for “visioning” not “doing”, while short-term catalytic actions are needed for “doing” and not long-term “visions”. A good way to test a comprehensive plan is to examine the section or elements aimed at implementation:

• Long term visions should be used for education, not short-term resource allocations

• Front end catalytic projects should be linked to specific resources and lead to longer term goals

• Roles and responsibilities should fit the capacity of local staff and agencies

• Outcomes should be monitored and used to update strategies and tactics

Another major area of debate concerns comprehensive plans in communities where all land is “fully developed” versus communities that have large unbuilt areas (often farms, woodlands, and wetlands) that can be developed for new subdivisions. Usually. local owners of open land want to sell their property (for a high value) to developers who will build new homes or businesses. Local residents want the open land to remain as such and do not want any “newcomers”. These debates lead to issues regarding property ownership, extensions of public services, social justice, racial segregation, class segregation, and many other highly contentious public policies. In these circumstances the planner’s role is to include, in the plan, the representative facts and figures, along with changes that embody basic ethical standards for community change. Even when the plan is balanced, legal battles and political actions emerge. For planners, this is a necessary part of their job.

Area Plans: City Centers, Neighborhoods, And Corridors

Perhaps the most prevalent form of special area plan is the downtown or central business district (CBD) plan. At one time such plans were found only in larger cities. Today a downtown plan can be found in many populous suburbs as well as smaller villages outside of metropolitan centers. Downtown areas provide the social and economic heart of the community. The way in which these areas are planned becomes a community-wide issue. At the same time, the allocation of resources to a downtown area often engenders “pushback” from officials and citizens who believe the balance of resources should shift further into residential neighborhoods.

Today the planning profession faces challenges not just in downtown, but in neighborhoods and corridors throughout the community. As downtown plans became more popular, so too did plans for neighborhoods surrounding a downtown. Many traditional urban neighborhoods, like downtowns, need a fresh look and analysis to see what issues (like gentrification or social/economic justice) might need improvement. The same is true of neighborhood business districts. As suburban shopping malls became more popular many neighborhood main streets suffered. In the last decade, many malls have become less successful and new attention is being given to local business corridors. The shift from retail purchases to online shopping has also impacted main streets and malls. Today the impact of the recent pandemic has further complicated the creation of area plans.

The organization of special area plan usually addresses some of the critical variable for public places noted previously as a sub-component of the comprehensive plan:

1. The visual form and character of the area: the grain and texture of the buildings, massing, street activation, public places, and composition

2. The history of the place: including traditional buildings, environmental conditions, and development patterns that should be maintained and extended

3. Circulation systems (all modes): vehicles, pedestrian, bicycles, transit, parking, intersections, prioritization, safety, and operation

4. Social and economic activity (going beyond land use): current and future value, social activity and diversity in public places, distribution of economic costs and benefits, capital and operating costs

5. Environmental features and critical conditions: climate change, natural and native plantings, microclimate, water and stormwater management, appearance and activity

6. Long term operation and sustainability of the area: costs and benefits for different groups as well as local government, task management.

7. Implementation: regulatory issues, economic subsidies, public/private partnerships, land assembly and control, incentives for change, and phasing.

For many years, a standard outcome of special area plans was the assembly of large tracts of land, demolition of buildings, the associated by displacement of families and businesses, and completely new development. Much of this was accomplished under the banner of urban renewal. However, this practice of broad area demolition (regardless of its name) has been used for decades. For example, New York City’s Central Park, which has become the much-lauded signature legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted, involved the social injustice of acquiring and demolishing Seneca Village – a community occupied by Africa Americans. Today, however, attitudes have shifted in response to the failure of many urban renewal efforts. Instead, communities recognize that revitalization of older neighborhoods and districts represents a more just and effective social and economic approach.

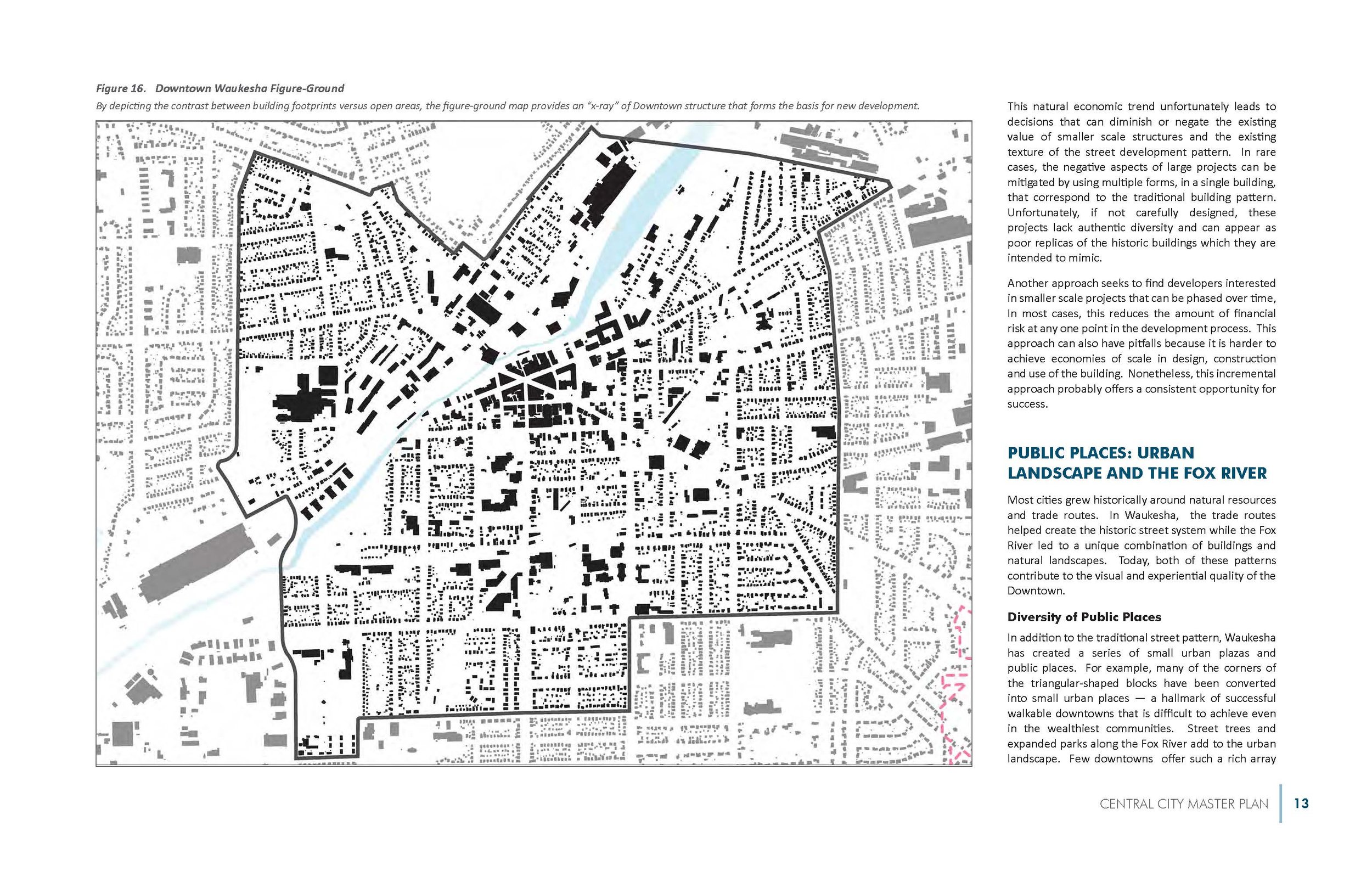

Urban designs and district plans should show both the pattern of new development integrated with the surrounding context. These pages from the Waukesha Central City Master Plan, show a variety of mapping and drawing techniques that allow the users of the plan to see both physical pattern as well as social and economic implications for the districts and neighborhoods of the community. Waukesha, WI, 2012.

As with downtown plans, local occupants of a neighborhood must become actively engaged in the planning process. Special area plans should always include provisions for different forms of community engagement. Sometimes this process is mandated by law, along with the specific methods and techniques to be used. More recently, however, use of digital communication technologies provides new tools which allow community engagement to be widespread, more in-depth, and aimed at a broad cross section of the community (not just those who can attend meetings or who have been energized by a single-purpose agenda).

The issue of gentrification and so-called neighborhood succession has induced many debates that echo the controversies in undeveloped greenfields. Here too, plans for neighborhood change should be balanced, fair and equitable. As noted, lack of fairness and social equity in land development is not, by any means, a new social phenomenon. Issues regarding the fairness of property development extend back millennia, even to biblical times. Each planner needs to find a way to address these moral dilemmas.

The proliferation of area plans in many cities has also led to another trend in which comprehensive community-wide plans are combined with local neighborhood, district and corridor plans. That is, local governments and agencies view plans as systems of critical thinking which evolve over time rather than a fixed set of recommendations at one moment.

Special Purpose Plans

At times, the lines between different types of plans become less clear. For example, a neighborhood built around a major college campus or healthcare institution can become both a special area plan (the neighborhood) as well as a special purpose plan (the institution). This overlap among different types of plans represents a positive trend. For example, in some communities, the geometry and geography separating residential and business areas from university buildings becomes blurred and plans for both types of arts should be merged (along with the difference in their higher-level missions). Examples of missions and visions which lead to creation of special purpose plans include:

• Create an entertainment center

• Increase local business

• Preserve the natural environmental

• Mitigate climate change

• Improve long term resilience and sustainability

• Generate alternative energy and manage energy demand

There plans include substantial information about the unique mission or purpose they address. Understanding the uniqueness of specific mission also requires including data regarding facilities, places, services, programs, and policies that are relevant. In addition, each type of special purpose plan usually involves an organization or agency that has authority over some of the critical resources and decision-making procedures that impact the plan.

The Sustainable Development Guide for Drexel Town Square represents a special purpose plan intended to implement specific sustainable development practices in a new city center development. Unlike many other guidebooks on sustainability that focus on broad general principles and, this guidebook identified specific site locations for implementation of each action along with a table of expected costs and benefits. Oak Creek, WI, 2014

Special plans can also focus on very small sites as part of a “placemaking” plan. In recent years, several trends have led communities to appreciate small gestures in urban design and landscape architecture which can enliven a local street or small public place. Such place-making interventions can become symbolic of a neighborhood’s resurgence, increase in business, and/or simply a celebration of public life. Placemaking plans do not usually involve major documents but rather a few simple illustrations and, on occasion, the drawings needed to construct the proposed design.

Plans for “Undeveloped” Land

Although included in many comprehensive plans, future development of open land – usually farms, woodlands, and wetlands – requires special attention from professional planners. Whether the use of undeveloped land is intended to be a simple residential subdivision or an entire new town, a responsive plan document needs to include substantial technical information about the land. This includes issues such as soil conditions, topography, environmental contamination, plant life, animal life, water flows, as so forth.

If the undeveloped land will support a larger population – perhaps enough households to be considered a new neighborhood – then the plan also needs to address a full range of public services from basic utilities to larger social issues such as education and health care. Typically, these types of plans focus on the issue of capacity of existing systems – both natural environmental systems as well as local social, cultural, and economic systems. Questions arise over how such systems will be provided, what they will cost, and who will pay for them. For example, if new housing brings more schoolchildren, the plan needs to address how that increase will impact local schools.

Historically, some plans for undeveloped land have included completely new towns. In the U.S.A. new towns include the greenbelt communities from the New Deal (such as Greendale, Wisconsin) as well as private sector communities including Kohler Wisconsin, Pullman Illinois, Columbia, Maryland and Reston, Virginia. More recently, some private sector “new urbanist” communities such as Seaside and Celebration have become well-known models. All of these new towns, as well as many throughout history, have involved the use of professional planners. Those plans represent a powerful record of planning outcomes some of which worked well and some of which did not survive.

Entitlement Reviews And Regulatory Documents

Perhaps the most common, but uncelebrated, document prepared by professional planners is the simple “planning review” of proposals brought before plan commissions, zoning boards, and other regulatory agencies overseeing applications from owners to change their property. Does a new proposal fit local plans? Does the change meet zoning codes, building codes, land division rules, environmental conditions, access and circulation rights, easements, conditional uses and many other regulatory issues? Often there is confusion over the distinction between zoning (which usually defines the owner’s current property rights) and the local plans (which usually define the community’s rights to guide change). Planners usually prepare the documents for the review by public and elected officials. When the answers are not clear, the planner needs to provide the recommended direction for the local governing body.

Often the answer is complicated. A plan review might recommend approval of an application “subject to” meeting certain conditions. Alternatively, the planner might recommend the opposite approach that the application should be rejected “unless certain conditions” are met. The plan review process can also be costly for an investor who wishes to gain approval quickly and an “entitlement” to build. A delay of one or two months in order to meet certain procedural rules might prevent a project from moving forward.

The planner must craft application reviews in a way which is fair to both the applicant and the community. The process becomes more complicated if the proposal from the applicant is viewed unfavorably by local neighbors. A common occurrence, for example, is the objections by owners who live in a recently constructed subdivision to a brand-new subdivision across the road which will bock their view of farmland. It is the planner’s responsibility to prepare a plan review document which is fair and equitable and facilitates the decision by local officials.

When public debates become overheated planners often face major lawsuits – either as a spokesperson for one of the parties in a lawsuit or as an outside expert witness offering a legal opinion. In these circumstances the planner needs to render an objective opinion, based on the reading and interpretation of regulations. Often these legal opinions may contradict the work and opinions of other planners. While this process seems far afield from notion of a planner seeking balance between different outcomes, it is, in fact, a critical role for planners to advocate opinions that lead to better planning and better planning judgements by communities and the general public.

The planned demolition of the highway corridor in Milwaukee, known as the Park East freeway, required highly detailed and precise polices and regulations for new development to be implemented over a 20 year build-out These excerpts illustrate how such regulations were planned on a block-by-block pattern (using a customized form-based code) which regulated visual character and intended social and economic activities. The plan has become a model for the revitalization of freeway corridors. Milwaukee, 2003

Topic summary

The Plan As A Document

Comprehensive (Long Term) Plans

Area Plans: City Centers, Neighborhoods, And Corridors

Special Purpose Plans

Plans for “Undeveloped” Land

Entitlement Reviews And Regulatory Documents