Cityland Essays

Fix Your Freeway

Fix Your City

Introduction: 50 Years of Back Seat Planning

Cities face chronic struggles with the planning, implementation, and deconstruction/reconstruction of urban freeways. Most planners have watched the way cities replace freeways amidst local controversy — with new streets, blocks, parks, buildings, and urban places. This set of three essays recognizes the importance of such political conflict but focuses more on how urban planners, in response to freeways, have evolved their approach to such issues over 50 years in one city – Milwaukee.

As a planner I have taught and practiced in Milwaukee since 1972. During this time numerous freeway-related transportation plans came forward, each with different potential impacts on urban conditions, opportunities and outcomes. These plans were initiated and largely formalized prior to significant urban planning work aimed at surrounding neighborhoods. Put another way, work as an urban planners was a bit like backseat driving since the transportation plans always came first. Now, in 2025, new plans have arrived for new major freeway transportation changes that will also involve surrounding urban places. This three-part look at both past and current plans for freeway system modification could help Milwaukee make wiser decisions that will impact future generations.

The first essay (Part 1) looks at five projects that occurred prior to 2025. (Locust Street, Park West, O’Donnell Park, and two projects for Park East). The second essay (Part 2) examines a case study, currently underway – the replacement of HWY 175. In the WIS 175 plan, three alternatives (two with a boulevard) replace the expressway within a complex set of neighborhoods and parks. The last essay (Part 3) examines a much bigger, strategic, and more transformational opportunity of replacing the 1.5-mile “keystone” section of I-794 as it traverses Milwaukee’s downtown. Collectively these essays may offer an urban planning analysis that can help improve our urban freeways, one place at a time.

Part 1: Accumulate Past Lessons

Understand How Urban Barriers Evolve

To begin an analysis of urban freeways and their impact on the city, we first have to understand how freeways have impacted urban areas by becoming embedded barriers which, in turn, have negative consequences. Some embedded urban barriers fit the essential form of the city like rivers, lakes, and major topographic changes. Over centuries planners found ways to transform natural barriers into assets that add value like desirable views, access to shorelines, and related features. Ancient aqueducts can add a sense of romance to a pastoral view, but transmission lines, pipelines, and similar structures have not yet become appealing.

In many cities, potentially negative barriers, go underground like subways, steam tunnels, sewer and water systems, and even some freeways. The large added cost of hiding infrastructure implies that, for many cities, the cost of avoiding harmful visual barriers deserves large expenditure. Boston’s Big Dig is a spectacular example of how the harm caused by freeway barriers was presumably cured by placing the freeway below ground (at great cost to all levels of government). In most cities, however, planners face infrastructure barriers with few redeeming opportunities.

Before Freeways: Railroads & Canals

The first signs of barriers in most cities appear with when railroad systems arrive. Many cities understood the problematic nature railroads and promptly built expensive tunnels or elevated tracks. Even those elevated tracks became problematic but, unlike freeways, they elevated rail systems allow for fully functioning at-grade streets. In response to new railroads new structures were built adjacent to the tracks. While freeways demand major interchanges, railroads use sidings and railyards that spawned large industrial and commercial facilities. Home built near railroad-based industries were well positioned for employees to walk to work.

Over time, visual and functional uses near railroads languished. Disinvestment settled in. Upgrades stopped. Other transportation systems (like freeways) gained value as a more efficient alternative. Today, century-old railroad conditions remain as part of the challenge to reconnect the communities. While “rails to trails” have given the older railroad rights-of-way new life, many railroad systems still debilitate urban areas. Mitigation of railroad barriers (especially urban railyards) occurs in many cities but rarely erases the decades-long legacy of negative urban impacts.

Some of the early railroad barriers have transformed from liabilities to assets. Perhaps the most well-known examples New York’s High Line. While not as prominent Milwaukee has several rails-to-trail projects demonstrating transformations of older rail systems into new assets (such as the Oak Leaf Trail and Hank Aaron trail). Milwaukee and other communities know that there must be a balance between the efficiency of urban, suburban and rural transportation systems.

Before the railroads, canal systems emerged echoing canal networks in European regions. Unlike railroads or freeways, when canals lose their industrial and commercial value, they retain their visual and cultural value. Adjacencies to canal can provide some of the highest and best real estate. The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal clearly adds value to Georgetown. Freeways, however, have yet to be perceived as inspiring aesthetic cultural objects, a condition confounds effective urban planning.

Split Neighborhoods & Disconnection

Freeways came with much larger structure than railroads as well as larger land areas for ramps and the needed arterial networks for traffic distribution. More importantly freeways also dominated the street level. While early elevated freeways allowed the local street system to continue at grade, eventually the logistics of maintaining and operating above grade structures exacerbated freeway barriers with dead or dormant street levels.

Areas around interchanges soon developed large auto-oriented structures with surface lots. Such development did not fit cities but became praiseworthy as it echoed newer suburbs. Over time, the edges of freeway barriers expanded and became either dormant or less attractive or both. Urban connectivity became more difficult, and loss of value rippled into surrounding neighborhoods. As freeways and railroads grew separated neighborhoods became more isolated.

Some separated neighborhoods grew stronger built upon their inherent, well-sustained structure of harmonious buildings organized on simple streets and blocks with small parcels and robust landscape patterns. Other neighborhoods with similar structure (perhaps on the “wrong side of the tracks”) grew weaker. In recent years, the dichotomies between neighborhoods have yielded issues of gentrification, segregation, and partisanship. Planners have yet to find ways to mitigate barriers and restore healthy patterns of integrated growth and revitalization.

Mitigate Barriers – Freeways And Neighborhoods Are One Entity

Developing freeways and developing neighborhoods both require the highest talents and skills. enormous levels of coordination, and major resources for financing, operations and innovation. You cannot “keep it simple”. Persons less familiar with freeways and neighborhoods, including professional designers in all fields, often fail (or refuse) to grasp the enormity of both challenges as independent problems. Now the challenge of integrating solutions to both sets of issues has become an even more “wicked” problem.

Decades of trial and error, success and failure, must be understood in order to co-develop major highways and neighborhoods. We cannot do one without the other. If we characterize the essence of freeways as “systems” and the essence of neighborhoods as “places” we may have a chance. At least, that seems to be the accumulated lesson from decades of such projects in Milwaukee.

Amongst our federal, state, and local governments we face chronic turbulence. Seeking at least partial rationality in this milieu seems Quixotic. Perhaps we are “tilting” at freeways, failing to see them as what they are, as well as what they could be. The decision-making quandaries regarding freeways and neighborhood places will not diminish. So, what can practice planners do?

Mediate City/Suburb Conflicts

Freeways must help, or at least not harm, urban, suburban and rural areas. This requires balanced planning for each type of community. Initially freeways created a great value by providing fast access across long distances. Such traffic movement required roadways with “limited access” that allow vehicles to move faster and safer. This was, and still is, an incredibly valuable service. Intercity and commuter train systems, for example, have been constantly improving. So too have freeway, but not always in a way that helps the neighborhoods that traverse. Any resolution will require viewing such systems and places in their full social, economic, and physical context.

Recognize How Urban Freeways Diminish Cities

Characteristics of limited access urban freeways conflict with the types of the circulation systems needed in urban areas. Urban areas do not require faster traffic and access, but better safer, comfortable access for more people to engage in more diverse activities. Higher density places, thrive on multiple modes of access to multiple places as opposed to freeways that thrive on singular access to separated interchanges. They both have their place.

Urban freeways reconfigure effective non-hierarchical patterns of access in neighborhoods into stricter, less flexible hierarchical patterns for regions. The freeway-based hierarchical model of traffic, ultimately trickles down within cities supporting segregated land uses, aided by zoning, and embedded by a legacy of property valuations. It has taken decades for planners to help reassert mixed use, multi-income neighborhoods, diverse social and cultural activities, and all of the other attributes that help urban areas thrive.

Freeways in suburban and rural areas exhibit the opposite traits. They provide the primary means of interconnecting distant areas and subareas to facilitate daily life. Suburban areas with segregated land uses, restrictive access, and less diversity are anathema in cities, but quite desirable in suburban districts. So why must we make suburbs be like cities or cities like suburbs? How can we accommodate both? How can they coexist? Too often our communities feel threatened by exaggerated warnings of change, xenophobia, and a loss of control. In the case of freeway changes, planners need to acknowledge such anxieties, address them fairly and directly. Wherever possible planners should emphasize clear examples of likely outcomes as opposed to alarmist doom and gloom scenarios. Many suburbs, in the long run, are much better off if their urban centers have higher value, more jobs, more interesting and desirable activities, and more revenue to support themselves.

Replace Urban Freeways with Good Boulevards

Freeways of course maximize one single variable – how fast you can drive safely from Point A to Point B. Other factors seem secondary including the cost of the vehicle and the fuel, aesthetics of the experience, impacts on the natural environment, and – especially important for urban areas – the social, economic, and political value of activity abutting the freeway. Detached urban freeways become impregnable barriers with their legitimate need for separated lanes, fences, guardrails, shoulders, and sound walls. The same freeway that does not help property owners in urban places will help the values in suburbs and rural areas where freeways make sense. In short, the key to mitigation becomes the transitions from city to suburb or, in this essay, the transition from freeway to boulevard.

When drivers reach the city and leave the urban freeway, they travel on a local arterial – a type of mini-freeway designed for fast traffic and vehicular movement. Effective arterials (with grassy medians and turn lanes) facilitate traffic but they should not be mistaken for urban boulevards. Most arterials lack the higher quality landscape, attractive facades, walkable features, slower speed and increased cross access that is essential to great boulevards. It may be hard to define the detailed different between a traffic oriented arterial and an urban boulevard, but most people know it when they see it.

Good boulevards offer maximum access to surrounding areas. They are designed for a high-quality aesthetic impact, slow speeds to ensure pedestrian comfort and safety, as well as integrated use of other vehicles like scooters and bicycles. In some ways boulevards are the direct opposite of freeways. Boulevards add neighborhood value with activated wide sidewalks, heavily treelined edges and harmonious (not identical) building facades.

Boulevards are clearly the roadway of choice for major traffic movements in urban areas while freeways are clearly the roadway of choice for major traffic movements in suburbs and rural communities – neither one mode nor the other is better, but they must be used in their appropriate setting. Freeways in cities are harmful just as boulevards on rural areas would be wasteful.

Balance Combined Value for City and Suburb

The ability to integrate both freeways and boulevards does not require a whole new skill set or volumes of analysis. It does require merging urban and suburban mindsets which, if left unbalanced and disconnected produces dysfunctional outcomes. This merger of dichotomous belief systems only occurs if planners emphasize long term costs and benefits that can create win-win scenarios.

Over time, improving the value of denser urban areas improves the value of surrounding suburbs. The central business district of each major city is, in practice, the economic and cultural heart of the metropolitan region. The more the central city “heart” thrives, the more the suburbs thrive. When central city areas become less valuable and less attractive, the primary option for growth quickly moves to the suburbs, adding more subdivisions, adding more traffic and exponentially higher infrastructure costs (especially on a per capita basis). Suburbs want short term property value but not long-term infrastructure costs that usually lurk a decade or two ahead of annual budgets. Many post-war suburbs that began in the second half of the 20th century, already have fallen prey to this predicament. Suburbs today, just like city centers, need to rethink their long-term futures.

Look Back To Look Forward

Sometimes hindsight shows us a way to move forward. Hausmann’s Paris provides, perhaps, one of the best benchmark for comprehensive streets. His boulevards have everything from the right technical engineering, enormous social and economic value, and new facades that make truly complete and beautiful streets. When Olmsted created Hausmann-like boulevards in the United States, he fashioned well-functioning boulevards (before cars) that still operate today at high levels of value as well as transportation efficiency (such as Eastern Parkway, Ocean Parkway and others). If these urban boulevards have worked for almost two centuries, then why cannot they work now? Why are good urban boulevards not replicated more often? Did we fail to recognize our older boulevards as good solutions because they lacked speed, because they supported transit, because they were not suburb-oriented, because they do not follow the most recent “best practice” guideline, or because they just seemed old-fashioned at a time when anything more recent must be better?

Freeways Interrupted — Milwaukee’s Accumulated Projects

This essay does not focus on why ‘freeway’ advocacy triumphed politically – planners have little authority to make such decisions. But if, and when, urban freeways enter a remission phase, planning questions become paramount. How does freeway remission actually work at grade? What issues should be addressed? What are the variations in context and conditions? How should freeway transformation be implemented?

Since the 1970s freeway-related projects have been modified to mitigate negative impacts in and around Milwaukee. Each of these projects faced varied conditions in which a freeway (or expressway) has been replaced or reconfigured. Typically, it is not the freeway changes that are ill-defined, but the surrounding urban conditions that account for the problem complexity. These complexities of urban areas surrounding freeways usually exhibit a much broader array of social and economic issues when compared to changes surrounding suburban and rural freeway. Each of the projects discussed here required wide-ranging talent and resources from planners representing different disciplines, skill sets, public missions and levels of government. Alos, the project time frames overlap but they are presented here roughly in the order in which they were initialized.

Recognize Neighborhood Preservation - Locust Street & The Growth Of Riverwest

In 1973, there were Department of Transportation (DOT) plans to widen Locust Street to facilitates its functionality as a freeway arterial that would connect the I-43 freeway interchange around 8th Street, eastward, on Locust Street, across the Milwaukee River, and through the wealthier university-based eastside neighborhood all the way to the lakefront (where the arterial might connect to a planned but never-built freeway system along the lakefront). The planned Locust Street arterial had already led to the demolition of several blocks of street frontage from 8th Street to Holton Avenue.

The demolished street frontage harmed, as might be expected, the largely black neighborhood abutting Locust Street. No redevelopment plans for the demolished area were put forward. The land stayed vacant and unsightly. East of Holton the Locust Street was still intact. An intense political battle ensued between the neighborhood group ESHAC and the City’s leadership over the potential future of the area. As a planner working for ESHAC we were tasked in demonstrating the potential value of the neighborhood both south and north of Locust streets and the need to treat the neighborhood as an integrated area with strong value. Two planning studies were produced: “Futures for Locust Street” and “The Riverwest Neighborhood Plan”. Eventually the City leadership relented, relabeled the area as a “special” neighborhood and allowed it to chart its destiny in a more independent, but integrated manner. Over the years Riverwest grew in value as one diverse neighborhood. Locust Street and Riverwest represent a clear success story in preventing a freeway arterial from extending its damaging influence. Most recently new development on Locust, west of Holton has begun more than 50 years after the initial arterial demolition.

Was there a unique planning issue underlying the strategy for saving Locust Street? In hindsight it seems the simple, critical issues was urban neighborhood preservation focused. This was not historic or architectural preservation – it was simply the social and economic preservation of Locust street as the unifying seam in a pedestrian friendly neighborhood. Not only has the neighborhood prospered, but Locust Street, and now Humboldt and Holton are also seeing signs of revitalization which can be expected to continue. Without the preservation of Locust Street activity, the story would not have ended successfully.

Overcome Disbelief - Park West Freeway 1974-1980

The Locust Street arterial dilemma did not involve new development. The potential for new growth to replace cleared land first occurred as part of efforts of the Park West Redevelopment Task Force. When the freeway system expansion was abandoned, several miles of cleared land became dormant and left vacant. The demolition process had occurred in increments but left an obvious swath of cleared land from Sherman Boulevard on the west to the lakefront on the east. The west half of this land (west of I-43) was labeled “Park West”.

The Park West land became the subject of a major neighborhood revitalization effort under the direction a consortium of local groups called the Park West Redevelopment Task Force. This Task Force undertook initiatives that were successful as well as some that were stopped. Today unused and underused land remains, but several key investments have occurred. Some of the positive outcomes included:

Forging coordination and cooperation amongst several disparate community groups that helped support better local services and policies

Creating a new County Park (Johnson Park) which remains a key community feature

Preparing the conceptual design and program for the Fondy Market which initially stalled due to a lack of City support but ultimately became a thriving community asset

Obtaining $2 million from the Economic Development Administration to start new business

Supporting the expansion of Washington High School on its existing land rather than demolishing additional neighborhood housing.

Stopping the demolition and widening of Fond du Lac Avenue as a proposed high-speed arterial to link to I-41 and reinvesting Fond du Lac as a key urban street.

The greatest difficulty was simply overcoming the disbelief of the general public that redevelopment of the area was feasible and that the homes that had been demolished could be replaced. The difficulty, however, was revitalizing the housing market without strong governmental support. Many of the investment successes noted above occurred because of public actions from the County, State, or Federal government – while City support was missing for a variety of political reasons. The best way to view these efforts from a planning perspective is to credit the Task Force for stopping the negative impacts of the planned freeway, creating several positive neighborhood changes, and setting the stage for future groups to improve the area.

Emphasize Opportunities – O’Donnell Park & The Downtown Lakefront

A primary hope for the planned freeway system was the continuation of the freeway from the north end of the Hoan Bridge along the downtown lakefront, turning west just north of the War Memorial parking lot. This would have created an enormous barrier separating the lakefront and the shoreline from the city. Access from the downtown bluff overlooking Lake Michigan had never been considered significant – such access was not diminished since it did not exist. Fortunately, the absence of a strong lakefront connection (visual and physical) was so overwhelming that all audiences knew that continuation of freeway construction would become the ultimate barrier killing connection from downtown to the lakefront.

In the late 1970s the City, County, and State conducted an international design competition to propose alternative visions for the lakefront. The competition winners were well received but no changes were made. A group of local citizens created an organization called the North Harbor Network to push forward some of the ideas from the competition. With assistance from designers from UWM (including myself and Harry Van Oudenallen) an alternative, award-winning, plan was put forward, promoted, and ultimately accepted by the County as the first key step in shelving the freeway plan and creating a large public park and cultural facility

While the initial design, called Lake Terrace, was changed substantially it was revised and renamed as O’Donnell Park in recognition of the leadership of County Executive O’Donnell. This project was the first domino which created a much larger series of lakefront transformation including the Milwaukee Art Museum expansion, Discovery World, Betty Brinn Children’s Museum, the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial, outdoor gardens, public art, and a much higher-level of public use.

This location on the Milwaukee lakefront still faces challenges to achieve higher levels of coordination and harmony amongst all the users. Put another way, the downtown lakefront improved immensely once the expanded freeway system was halted but it now faces constraints and opportunities to create a new integrated system for traffic and land use.

Find The Vision - The First Park East (Reuse Dormant Land)

As part of the freeway system the federal government purchased a cleared land from the lakefront to the I-43 freeway, referred to as the Park East extension. About half of the land (from Jefferson Street east to Lake Michigan) was cleared and sat vacant for many years. The vacant land was “demapped”, taken off the freeway system plan, and placed under local government control. The land further west (from Jefferson Street to I-43) became the subject of the much larger and significant freeway replacement project called “Park East” and discussed in the next section of this essay.

The right-of-way for this eastern section of I-194 was cleared, but nothing was built pending the fate of the freeway along the lakefront. When plans for the lakefront freeway were set aside, this land became one of the most valuable downtown opportunities for new development. The opportunities seemed simple but were still controversial. For several years the UWM School of Architecture and Urban planning repeatedly used the vacant land as a basis for studio projects for new housing and neighborhood development. I was one of several faculty members who promoted and disseminated the concepts.

One of the local developers, Mandell and Associates, clearly recognized the potential promise of the land and implemented several successful new developments. The full plan used the land for a variety of housing types (townhomes, apartment rentals, condominiums), a retail core, and well-planned parks and garden areas. Most importantly the vacant land was transformed from a barrier (between the downtown and the lower east side) into a harmonious fabric which knitted the different areas together. It also became a model for future development of the demolished I-194 freeway in the next decade.

Unlike the prior study of Park West, and the work on Locust Street, this area was ripe for market-based development. The area was already improving with new townhomes and retail activity. The downtown decline had stopped, and new investment was imminent. Several different types of housing and retail projects emerged. For most newcomers to Milwaukee there is no obvious separation between the development of the vacant land and the prior development in the surrounding neighborhood. It is a seamless transition. The complete absence of the freeway allowed this land to become a high-value, easily accessible, visually attractive, urban place. This outcome proves that the response to the marketplace may require effective long-term market evaluation rather than short-term “impulses” that respond to the immediate market.

Invest In The Next Generation - The Second Park East (Remove & Replace)

By the year 2000 the strong property market became evident in the downtown adjacent to the freeway (I-194). Nevertheless, the freeway removal and replacement required strong political leadership. Once approved, over 30 blocks became available including both the demapped right-of-way for the Park East corridor in addition to nearby parcels. This became the most complex freeway project at the time. The urban planning and design strategy needed to create good urban places through a regulating plan and a form-based code. Components of those documents, mentioned in two other essays on this website, are repeated here.

Enormous public opposition arose about the rationality of removing and replacing the freeway with local property development. Here are three of the major position arguments and outcomes:

Opponents predicted that the large volume (40,000 cars per day) would not be able to enter and leave the downtown effectively. In practice McKinley Boulevard handles the 40,000 cars per day which are actually dispersed more easily than the prior freeway.

Opponents stated that new property would never be developed and, if it was, it would not be high value. New development exceeded everyone’s expectations and even produced a surplus of TIF funds used to support other downtown projects.

Once it was clear that development would occur, naysayers said it would take too long -- that is it would take more than a year or two. Immediate short-erm redevelopment was never planned nor would it be a good strategy. Redevelopment was planned to occur over a twenty-year time frame so it could be phased and adjusted as needed. It began in 2003, and outlasted the pandemic, the Great Recession, bitter partisan fights, and ultimately achieved a 90% build out by 2023.

Essentially the redevelopment plan required a block-by-block analysis of market potential and capacity. The planning team created and evaluated several street and block plans as well as building a large scale 3-D model to facilitate collective discussion and workshop-style decision making. Here are some key issues in the planning effort.

Accommodate high speed traffic exiting and entering the freeway.

Preserve older historic buildings part of the old brewery neighborhood.

Assume that hillside transitioning will occur later, from downtown to the highly segregated neighborhood to the north

Avoid numerous urban renewal projects that had destroyed much of the historic value.

Make sure the new district that could accommodate the old sports arena.

Promote old and new riverfront buildings on both sides of the Milwaukee River.

Create geometries that fit a mix of both grids and curvilinear streets to accommodate the needed complex street and block geometries.

Incorporate transition areas to the local campus of the Milwaukee School of Engineering.

Harmonize with smaller scale residential housing that was part of the Brady Street neighborhood.

After the plan was adopted, The first project (the Flat Iron apartments) became “proof of concept” and soon other parcels were in planning stages. As noted, the expected twenty-year build-out actually occurred in a slightly shorter time frame. Perhaps the most interesting outcome has been recognition that the poorer, largely black areas north of new development were also impacted positively with reinvestment and value without gentrification.

What Cumulative Lessons Were Learned?

All of the projects noted above contributed to the detailed learning process for local planning practitioners and designers. The key lesson is that each freeway has a unique neighborhood with different constraints and opportunities for making effective urban places. Unlike engineering design for the freeway itself, which using standardized design principles (to ensure drivers will have a predictable and safe driving experience) urban places usually require customized dimensions and geometries to fit the undue context of each block and local street. Based on this approach here are the critical lessons:

Respect & Respond To The Urban Form Of Streets, Blocks & Buildings

Urban form and geometry grow accretive, over time, to create the street, block, parcel, lot and building forms that become neighborhoods and districts. When planning for revitalized areas around freeways the first step requires evaluating these patterns, historical and contemporary, and understanding the constraints and opportunities for improving urban places. Creating entirely new discontinuous forms does not make places “innovative”. Instead “new” forms usually worsen the barriers and separations among places and neighborhoods. With effective talent and skill Innovation can occur harmoniously, respect and respond to existing urban patterns and avoid making existing problems even worse.

Evaluate How Freeways Impact Social And Economic Conditions

As freeways grew and expended, their surrounding context changed with negative impacts on local demographic, social and economic conditions. Community planners must understand this history, evaluate the relative values of these changes and identify conditions that should be preserved, diminished, modified, and/or improved.

Focus On Long-Term Impact, Outlast Markets

Although the plans for addressing neighborhood impacts usually focus on the immediate and short-term outcomes, in practice, plans should focus, instead, on long-term impacts and leverage opportunities for broader positive changes. Market conditions at the time plans are crafted have a major influence on public perception and investor reaction. In practice, however, the neighborhood impacts of fluctuate through a longer time frame. Consequently, the plans should be designed to fit different market trends over time (not just in the initial years of post-freeway investment).

Include Leapfrog Opportunities

Neighborhood impacts aim primarily at the immediate areas surrounding freeways or adjacent parcels. In practice, positive impacts can often leapfrog to nearby, non-adjacent sites. As neighborhood awareness and potential values increase and leapfrog impacts can reach a broader area. The most successful leapfrog impacts respond to specific contextual features.

Engage multiple communities and stakeholders

Every change brings community controversy. Communication strategies based on effective community engagement can change such circumstances into less negative and more valuable and balanced outcomes.

Part 2: Reconnect Neighbohoods

WIS175 and the Search for Critical Places

In 2021 the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) initiated the “Reconnecting Communities Program” to fix freeways in urban areas:

“the purpose of the [Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program] is to reconnect communities by removing, retrofitting, or mitigating transportation facilities like highways or rail lines that create barriers to community connectivity, including to mobility, access, or economic development. The program provides technical assistance and grant funding for planning and capital construction to address infrastructure barriers, reconnect communities, and improve peoples’ lives.”

This program funded a feasibility study for the WIS 175 expressway over a two-mile segment spans across a highly diverse set of neighborhoods, districts, and subareas. The places in the overall study area have been “disconnected” – pulled apart over decades by the freeway, railroad, topography and public policies. The reconnection strategy for this area began by understanding the historic circumstances and acknowledging, from the outset, that there is no single or simple method for reconnection. Foremost, the pattern of urban from surrounding WIS 175 was evaluated and the pattern of urban form was viewed through the lens of social and economic conditions which have impacted reconnection.

Social & Economic Condtions

Volumes of data measure the social, economic, and political facts of the WIS 175 area. Not all data, however, bears relevance to evaluating feasible strategies for reconnection. Relevant data comes from viewing the issues of disconnection in an historic and geographic context. These data lead to the following useful knowledge about Washington Park, the character of neighborhoods and housings, and the legacy of social and economic inequities.

Washington Park – The Nucleus for Reconnection

WIS 175 borders the entire west edge of Washington Park. In addition, arterial links from WIS 175 extend along both the north and south edges. In sum, WIS 175 and its linkages surround the park and impact its use and value. Conversations among planners, engineers, government agencies, and local community groups routinely emphasize the significance of Washington Park as the heart of the community.

The landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, envisioned a park that was central to the whole city (like Central Park in New York City, albeit much smaller). Olmsted believed that city residents from all backgrounds should have a place to come together in nature. Washington Park was intended to appeal to a wide variety of people, economic classes, and population groups. The park is, a place to socialize, relax, and enjoy the rejuvenating powers of a natural setting.

Many still see Washington Park as a “jewel in the crown” of Milwaukee’s. park system. Since the 1890’s, however, some of the park’s vitality has been lost. On the other hand, the park still has potential to restore some of its urban prominence, continue to integrate nature into the everyday life of the City, serve ongoing community needs and, importantly, catalyze opportunities for urban reconnection.

New or expanded activities and facilities should increase socialization. Such an objective does not rely so much on better traffic engineering, but it does intertwine almost entirely with neighborhood reconnection. Olmsted planned places to meet with friends and to be enjoyed across class boundaries. He emphasized lagoons in many of his parks as social centers for boating and ice skating. Today’s Urban Ecology Center may not duplicate his plans exactly, but it clearly echoes his aspirations in a contemporary manner. The zoo and racetrack are gone but the park still draws visitors and fosters a sense of wonder in nature. The bandshell and music events have remained strong. Picnics may have diminished, but barbecues and tailgating have emerged. The playgrounds, ball fields and a hopefully renewed swimming facility are all consistent with his vision.

Neighborhoods & Housing

Multiple neighborhoods surround Washington Park and abut WIS 175. These neighborhoods contain a wide range of strengths and weaknesses and offer major opportunities for improvements. The housing options in local neighborhoods serve people at different stages of life and different socioeconomic backgrounds. Several housing pockets in these neighborhoods are culturally distinct and have a unique look and feel – an historic condition worthy of preservation. A diverse housing stock helps drive economic resilience to the periodic shifts in the housing market. At the same time, weaknesses in housing economics include lower household incomes, lower home ownership rates, and higher numbers of vacant properties. It will be important to maintain economic diversity, improve value, retain affordability, but avoid gentrification.

Housing types in the study area include single-family homes, upper/lower duplexes, and multi-family buildings ranging from a few units to 20 or more units. Nearby multifamily developments include even larger numbers of units. This housing stock supports multiple lifestyles. Unit sizes also vary which further supports income diversity. However, east of Washington Park and north of Lloyd Street the vacancy rates, property value, and the home ownership rates, are much lower. AS might be expected these areas exhibit with higher poverty rates and levels of racial segregation. In neighborhoods west and south of Washington Park the economic metrics are stronger, especially the Washington Heights neighborhood.

Proximity to job centers can help drive economic development provided local transit systems can be strengthened. For example, the neighbors are reasonably close to Downtown Milwaukee, Marquette University, Harley-Davidson, Molson Coors, the Milwaukee Regional Medical Center (MRMC), and the Veterans Administration Medical Center. Here, the key to “reconnection” includes broader, more convenient transit.

A Legacy Of Generational Inequities

A long-term legacy of social and economic injustice overshadows the diverse milieu of people in the project area. While social and economic inequities may not be a first-order impact caused by freeways, they do create secondary impacts which, over time, can be far more damaging and lead to permanent inequities in local neighborhoods. These inequities do not impact all residents at all times, but they add up over decades to create a legacy of long-term inequitable impacts. Some examples:

In the 1930’s, the federal Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) mapped neighborhoods on a scale of investment risk (high risk areas were shaded red). Areas labeled high risk were colored red. In became increasingly difficult to obtain mortgages at reasonable rates in these “red-lined” blocks. Over years initial inequity has embedded a chronic cycle of reduced ownership, lower maintenance and physical deterioration. When combined with other social inequities it can still be an overwhelming obstacle to families wanting to buy homes.

Energy burden is also an equity issue. As building insulation and home appliances age they require more energy, especially when measured as a percentage of household income. Over time the scope of work needed for energy efficiency exceeds the resources of occupants and incentivizes absentee owners to avoid improvements.

People who live, work, or attend school near major roads also have an increased incidence and severity of health problems associated with air pollution (asthma, cardiovascular development, disease, impaired lung pre-term and low-birthweight infants, childhood leukemia, premature death). Again, this may not impact everyone every day, but collectively over time this chronic condition creates clear inequities.

These inequities need to be recognized as part of the reconnection problem. New development should not only avoid such inequities but also remediate the legacy that still exists.

Build for Development Capacity & Long-Term Markets

The weakened real estate market conditions in specific subareas of these neighborhood may not be insurmountable. Many local conditions are susceptible to positive change over the long-term, especially investors see game-changing improvements in Washington Park and the WIS 175 redevelopment. Several other conditions also should be considered as positive features supporting local market capacity:

City Homes (17th and Walnut Streets) succeeded despite negative market expectations. The key was using local brokers to sell homes, subsidizing units, and creating strong visual appeal.

The Housing Authority of the City of Milwaukee (HACM) has successfully implemented small scale projects (10-20 units) in multiple neighborhoods that work well and offer housing options priced for affordability.

HACM also helped create the award-winning Westlawn neighborhood with strong visual appeal and a diversity of housing types across a large area.

The Community Development Alliance (CDA) established a program for affordable housing ownership that is feasible and should be used in this project.

The Park West area (noted previously) was weak, but still produced net improvements in surrounding areas, including the Fondy Market, Johnson Park, new industrial development and modest housing along Sherman Boulevard.

The Park East (east of Jefferson St. to Lake Michigan) filled in at a steady pace and today is fully reconnected linking downtown up to Brady Street.

The MRMC has created a major economic boom over the last 25 years in Wauwatosa. Some of this wealth has migrated to less than a half of a mile from the study area.

National Avenue is envisioned as a complete street corridor with multi-modal access for pedestrians, bikes, transit, and personal vehicles and offers a good example for the business development that can occur along WIS 175

The legacy of Washington Heights can be used as a major appeal for developers.

Urban Form / Urban Design

The physical foundation for “reconnection” rests on the integrated geometry of the streets, blocks, parcels, lots, built forms, architectural styles, landscape, and parking systems. This variable – urban form – combines with the social and economic conditions noted previously. All merge to create the urban “texture” or “fabric” that weaves neighborhoods together. These patterns, when analyzed and integrated, can create community reconnection. The analysis of the patterns of urban form surrounding WIS 175 yields five distinct types of places delineated in a diagram and described in more detail along with the accompanying evaluation of the reconnection issues:

Place 1. The Washington Park Perimeter (Public Perception)

Washington Park became the heart of this community before the freeway and still remains the living symbol of the area. If the park goes downhill and loses its value, reconnection becomes impossible. The exterior appearance, along the perimeter, determines general public’s view of the park. If public perception improves, other improvements will gain political support, Three physical features need to be addressed to improve:

The curb appeal on the private property across from the park. Private property must be maintained and improved included building facades and landscaping.

The public right-of-way must look orderly, well maintained, and safer with improved sidewalks, streetlights, furnishings, paving patterns, street parking, and signage. Pedestrian crossing at key intersections (especially at the four corners of the park) must be prioritized.

The landscaped edge of the parkland should be more interesting and attractive. with repaired walkways, trails, lighting and related features.

Place 2. The Washington Park Interior (Social Activation)

While it has not direct link to WIS 175 traffic, the park’s interior design and activities also determine the value as judged general public. If the public value park activities they will value the neighborhoods which, in turn, will improve reconnection. Currently activities must be sustained including music in the bandshell, the urban ecology center, senior center, playgrounds athletic fields, The swimming pool must be reopened and improved. Other activities should be considered including a farmers’ market pilot facility; and or a family-oriented food and beverage facility

Place 3. West Side of Washington Park (Value and Revenue)

The land west of Washington Park within the current WIS 175 right-of-way should be redeveloped to add value and revenue. New development can reinforce the traditional neighborhood design, increase multiple access points and add value at all economic levels with:

Small-scale townhomes (facing neighborhood homes)

Moderate-scale apartment buildings with 3-5 stories (facing the park and businesses)

Safe and easy pedestrian crossings

Garden areas (with access)

Place 4. Neighborhood Crossroads & Main Streets (Goods and Services)

Long-term social and economic reconnection requires revitalization of robust business activities along neighborhood main streets and hubs focused around:

Lisbon Avenue and Lloyd Street

Vliet Street

State Street

Wisconsin Avenue and Bluemound Road

Place 5. Underused Hillside Land (A New Neighborhood)

The dramatic topographic change from Vliet Street down the hillside to State Street defines a unique geographic area for both new natural areas and development. A new right-of-way configuration from Vliet Street to State Street may offer opportunities for unique development, environmental preservation and for connecting natural areas:

New housing with spectacular views as well as direct access to natural amenities.

Environmental conservation and community access to trails and wooded areas.

Connections to Hawthorne Glenn to the west and environmental corridors to the Menomonee River Valley

Urban Design for Reconnection

Urban design solutions should address reconnection in all of the places noted above. Proposals must also accommodate a transportation and traffic alternative that meets the needs and services as defined by WisDOT. This type of combined problem solving – transportation and urban design – has become increasingly important in the last decade as infrastructure problems get worse.

On linear corridors of multiple urban blocks, the market for new development shift incrementally with each block. The area around WIS 175 evidences a high variation in market conditions. It is essential to provide clear flexibility in the types of developments that can be created. The alternative discussed in this essay focus on residential development but include retail goods and services as well as cultural and non-profit activities. These alternatives assume growth will reach development capacity over time, using building forms and concepts consistent with both traditional neighborhood character and modest growth trend. As development unfolds, new TIF revenue will accumulate, some of which can aid affordable housing and risk reduction strategies.

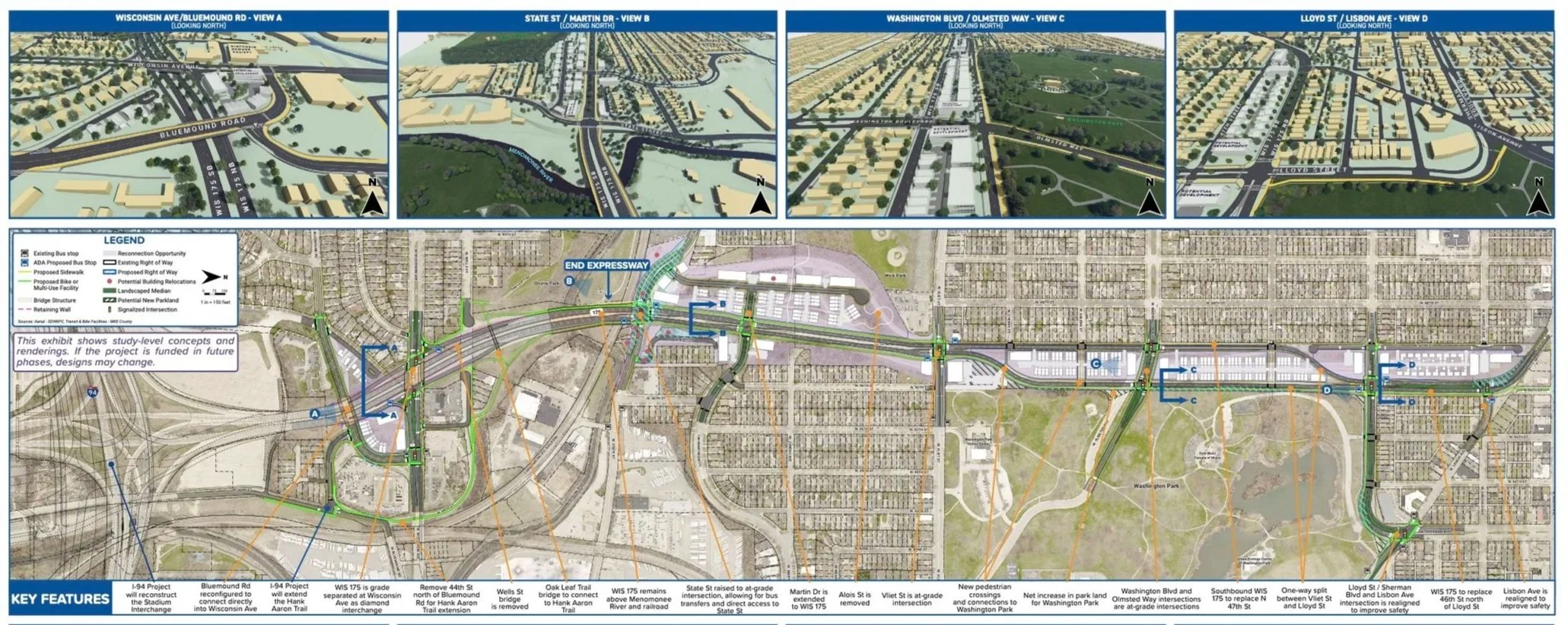

This essay presents only two of the three plans put forth by WisDOT. Those three options were labeled according to transportation planning concepts as follows: (1) end the freeway at North Avenue, (2) end the freeway at the midpoint, and (3) end the freeway to the south. From the perspective of reconnection (the focus of this essay) only the last two options address reconnection effectively. Consequently, for this essay these last two plans are presented and renamed “partial reconnection” and “full reconnection”. Readers are encouraged to view more details of all three options online.

In these two plans, “reconnecting” neighborhoods does not equate to the “highest and best use” principle in the field of property development. In the past the highest and best use speaks to the short-term return on investment for the property owner – not the long-term community wide value. Both views are valid, but only the latter view supports reconnection.

In this project, two viewpoints were combined: planning for (1) the best transportation solutions and (2) the best community-wide reconnection. This way of thinking yields two reasonable plans as follows:

Preferred Plan for Full Reconnection

The boulevard and an improved street grid begin near Wells and State streets. This alternative provides reconnection opportunities for almost the entire corridor and dramatically increases the probability of long-term reconnection. A more robust urban design is illustrated in this full reconnection alternative with lots of opportunities for incremental changes as development markets shift over time. This option reconnects the areas east and west of WIS 175 and along the entire north/south corridor (from North Avenue to Bluemound Road).

Moderate Plan for Partial Reconnection

The boulevard and improved street grid begin near the middle of the corridor, between State Street and Martin Drive. This alternative provides significant reconnection for about half of the length of the WIS 175 corridor included in the study. This urban design envisions a less valuable pattern of built form compared to the “full reconnection” plan. Nonetheless it offers discrete segments of development clusters, while still allowing for the street grid to continue through key location to Wahington Park. A wider boulevard replaces part of the expressway and uses a curvilinear alignment along the west edge of the park to slow traffic but still express an urban image. Unfortunately, north-south reconnection is diminished where the expressway remains south of Vliet Street where it transitions to a boulevard

These data are approximations and reflect the work the author undertook while he was working at Graef, Inc. They reflect his opinions and judgements. New data from Graef and/or WisDOT may change these estimates.

Plan for the Washington Park Perimeter

Moderate Plan: A new “garden walk” with a modest landscape borders the west side of the new boulevard to enhance the value and image of the housing clusters. This garden walk, when combined with improvements around the other three edges of the park will help residents view the park as reconnected along all four sides. The north and west edges of the park are also enhanced with a continuation of the Hank Aaron trail. Improved park edges will boost the values along the south, east, and north edges. This requires investment in streetscaping, improved park landscaping adjacent to the right-of-way, street resurfacing, and owner-based property improvements such as façade repairs, painting, and siding. Collectively, these will boost the perceived value and marketability of housing in the area in both the short and long term.

Preferred Plan: In the full reconnection preferred option, there is a much stronger and valuable edge condition on the west side of Washington Park because of a wider garden walk, more connections to housing, and a narrower street between the housing and the park. This added improvement will reinforce developer interest in investment, especially if the remaining perimeter of Washington Park is also improved. In addition, the Hank Aaron trail continues along the park perimeter. Other improvements are similar to the “partial reconnection” option including streetscaping, improved adjacent park land, street resurfacing, and owner-based property improvements such as façade repairs, painting/siding, and continuation of the historic character. Collectively this design will boost the perceived value and marketability of housing in the area in the short and long term.

Plan for the Washington Park Interior

Moderate Plan: The reconnection to all neighborhoods requires improvement to the park interior. Current park activities, including Urban Ecology Center, senior center, and bandshell, help sustain the perceived value of the park and boost the appeal of the surrounding area. Other improvements should include:

Expansion of the senior center

A farmers’ market (as a source of nutritious food, as well as a social meeting place)

Reinvestment in the pool (repairs or rebuild)

A family-oriented restaurant

Collectively such new and continued functions demonstrate the public’s commitment to the park, reduce the perceived risks and increase the perceived rewards from new development.

Preferred Plan: As in the “moderate plan”, new park improvements should include the pool, a farmers’ market, and family restaurant. It is worth emphasizing that a refurbished or new pool will also help restore confidence for both local and new investors. Along with the Urban Ecology Center, senior center and bandshell, this will dramatically increase the perceived value of the park and boost the appeal of the surrounding area. This design option also allows for expansion and or relocation of the senior center.

Plan for Redevelopment of the West Side of the Park

Moderate Plan: The moderate plan option locates new residential units in the expressway’s current right-of-way. These residences have views and easy access to/from the park. Direct, at-grade connections on Lloyd and Vine streets, Washington Boulevard, Galena, Cherry, and Vliet streets are critical to the social and economic value of each block. The built forms harmonize with the buildings and streets of the neighborhood. Market appeal can be improved by emphasizing the “garden walk” (emphasized more effectively in the preferred design option). The plan also includes small-scale semi-public places with quiet, intimate gardens that, from a market perspective, are more likely to attract higher value-creating investors. A diversity of housing types and built forms includes 2-3-story townhomes and 3-5-story apartment buildings along the north and south ends of each block. This will facilitate mixed-income housing, avoid the appearance of a single project, and match the visual diversity in the neighborhood.

Preferred Plan: This urban design offers many more options for the design and diversity of residential units on the former expressway right-of-way. Appealing housing locations are linked to views of the park as well as safe, comfortable and enjoyable access. The diversity of building opportunities allows for more visual diversity and therefor greater harmony with Washington Heights. The garden walk links housing not only to the park but also to activities further south and into the valley. A direct, at grade connection on Lloyd, Vine, Washington Boulevard, Galena, Cherry, and Vliet streets is also critical to the market value for each block. There is greater diversity of possible housing development plans in the preferred option with both 2-3 story town homes as well as 3-5 story apartment buildings along the north and south ends of each block. This can ensure market options for mixed income housing stock within each block and along each street edge. The areas where the parcel geometry does not favor marketable buildings can be used for small-scale public places that are quiet, intimate gardens that, from a market perspective, are more likely to attract higher value-seeking occupants.

Plan for Crossroads & Main Streets

Moderate Plan: The four at-grade intersections at North Avenue, Lisbon Avenue, Lloyd Street and Vliet Street all establish a sustainable market opportunity for nonresidential community-oriented investments. At first, they may focus on small businesses that are oriented towards the local population, but, if they include new types of uses, they will create a strong sense of reconnection. The degree to which these intersections promote reconnection and increase the perceived market value will depend largely on (a) creating pedestrian connections that are safe, appealing, and encouraging and (b) convenient access for local parking and bicycle movement. The hubs along Wisconsin Avenue (near the BRT) and State Street are isolated but may experience increase in value. In this alternative the development pattern is largely self-contained and may appeal to investors independent of the other areas.

Preferred Plan: The four at grade intersections at North, Lisbon, Lloyd and Vliet streets all establish a much stronger long-term, market opportunity for nonresidential community-oriented investments. They too will focus on small businesses that are oriented to the local population and will create a strong sense of reconnection. As with the moderate design option, the degree promotion of reconnection depends on creating good pedestrian connections and convenient access for local parking and bicycle movement. The major difference when compared the moderate design option is the new at-grade intersection at State Street. This is a powerful opportunity to boost the market value of the overall project. This design concept requires some relocations which can be mitigated but, in return, it creates an entirely new development opportunity. This option creates an economic gateway to the area by integrating the growing development potential east-west on State with the potential growth north-south on WIS 175. The hub along Wisconsin Avenue may be perceived as highly isolated and but can still increase in value in the long term assuming the BRT succeeds. The development pattern is largely self-contained but, if viewed in conjunction with the economic opportunity at State Street can increase the perceived value of the boulevard and this location.

Plan for Underused Hillside Land

Moderate Plan: The hillside is an especially high value area for potential development. These units will be perceived as a relatively independent enclave of housing. It can include both smaller scale townhomes as well as large apartments along the edge of the boulevard. Over time, this enclave will be perceived as a natural neighborhood extension of development along the northern sections of WIS 175 to Lisbon Avenue. Housing in this are also includes potentially attractive park and environmental features to the west (Wick Field), other nearby environmental features and appealing “long views” over the valley.

Preferred Plan: In this urban design concept, the hillside is a stronger, more cohesive high value area for potential development. These units will be perceived as a stronger independent enclave. It too can include both smaller scale townhomes as well as large apartments along the edge of the boulevard. The at-grade intersection at State Street is especially critical to the market value of the overall project. This can boost market opportunities for non-residential uses at this location. Housing in this area includes potentially attractive park space to the west (Wick Field) as well as current environmental areas. As with the moderate plan option, this enclave will be perceived as a natural neighborhood extension of development along the northern sections of WIS 175 to Lisbon Avenue. Collectively this will create a strong market perception, especially if the development is designed and planned with continuity.

Plan For Reducing Ineqities & Builidng Equitable Wealth

In any plans the risk for new private development needs to be mitigated though support from other public agencies. Achieving risk reduction is always a controversial subject but it is also necessary. The urban design concepts in these proposals offer a variety of ways to reduce market risk. At the same time, reduction of market risks should be paired with reductions in inequities. Agreements or policies can be proposed for effective affordable housing along with TIF financing and subsidies.

While WIS 175 replacement needed to resolve inequities, it is only one part of the answer. Other urban policies and programs – both public and private – must contribute to overcoming the historic economic and social inequities in the study area. Two of the most important conditions to overcome are the lack of landownership opportunities and the lack of available financing for historically marginalized population groups in the study area.

Urban policies must on community wealth building programs. Specifically, in the case of reconnecting the neighborhoods surrounding WIS 175, remediation of the negative socioeconomic outcomes of the last several decades requires neighborhood wealth building. Neighborhood wealth building builds on the principle of property ownership and emphasizes the importance of community-backed development. In this model, cities should be major landowners while establishing reconnection programs and policies. Put simply, cities must exercise much greater control over urban development.

Cities as corporate entities can own and develop land. While they can always regulate the value of land through zoning, as owners they can regulate outcomes, property management, buy/sell agreements, deed restrictions, etc. As noted elsewhere, the City of Milwaukee can build and rent units, lease land to other owners, or establish direct developer agreements with new owners to enable and require reconnection outcomes. Developer agreements between the owner/seller and a new lease or deed restrictions can specify uses and policies in terms of parking, view corridors, building heights, rent structure, and sales structure.

While the state and WisDOT do not need to participate in this approach, they can assist directly by eliminating compensation for land disposition to mitigate the historic impact of inequities. If the City establishes a program for neighborhood wealth building (or, in terms of this project, “neighborhood wealth reconnection”), WisDOT could forgo payments for the transaction as compensation for decades of neighborhood wealth debilitation.

The Road Forward

At this time, fall 2025, the planning process has not been completed. Additional analysis may prevent adoption of the two plans described above for any or all of the following reasons:

Higher Level Jurisdictional Shifts To Shelve the Project

State or federal level policies or funding might reduce or eliminate the goal of “reconnection” thereby decreasing the degree of reconnection, the redevelopment potential, the funding for improvements, or related matters. This type of major shift in the implementation process occurs in many cases, especially due to changes in political leadership or local economic conditions. IN some cases, for example (like the Park West project), local government completely shelves the project in favor of other priorities.

Changes In Project Goals To Ignore the Reconnection Mission

Local community priorities always change and, in cases like reimagining Wis 175, can change pans significantly. For example:

It may be decided not to include any new residential development (this might dramatically reduce the opportunities to generate public revenue for related neighborhood improvements)

Conduct the project in phases such that the most significant changes (in and around Washington Park) are postponed indefinitely

Change the funding for internal Washington Park Improvements

The City or County may decide to transfer and ownership to other private organizations (both for-profit and/or not-for-profit) who, in turn, might change the goals for redevelopment from neighborhood reconnection to other community goals. For example, a private sector developer might choose to build 5 story buildings at one end of the corridor and then await market shifts before developing a subsequent parcel. Alternatively, a developer or not-for-profit agency might wish to build affordable housing units for large areas of land and avoid the complexity multi-income housing.

Plan Adoption To Implement Reconnection

The most difficult andmost appropriate challenge will be adopting either of the plans (moderate reconnection or preferred reconnection). Both versions will require:

A regulatory framework (like form-based code or regulating plan) to ensure that all opportunities remain open for effective reconnection

A funding agreement among the various levels of government involved in the project success (State, County, and City) which, in turn, might include some shared funding investments.

A not-for-profit agency that can manage a complex development scenario inclusive of both market-rate housing as well as affordable housing.

A redevelopment plan, adopted by the City, inclusive of options for community wealth building (such as a “land development trust” or equivalent group that can specific detailed development t concepts that fit the neighbors)

While this last pathway forward may be closest to the initial project goas, past experience hit freeway projects has taught us that implementation only occurs with continued perseverance on the part of the local community and leadership.

Mixed Futures – The Long Term For 2035

All of the freeway projects noted in these essays unfold over a longer time period, often with many ups and downs along the way. The future change of neighborhoods around WIS 175 is just starting. The plans shown here are good starting points, but it will take another 10 years at least to get a sense of the ultimate direction.

The implementation scenarios described here represent just a few possible directions. In practice every freeway project leads to some sort of change often incorporating some of the proposed recommendations. Readers interested in the process might wish to follow future changes in the WIS 175 neighborhoods over the next decade.

Part 3: Generational Shift From Freeways To Boulevards and Neighborhoods

End Our Senior Affair With Freeways — Fix Freeways For Future Generations

As a Boomer, I was born into the wonder of freeways. As an architect, I still view freeways as the awesome Roman aqueducts of our time. But as a Milwaukee resident since 1972, I have outgrown my Boomer freeway crush. it’s time for my generation to respond to changing values for the next generations and plan our city for their future. This matters more than ever, as we design the future of I-794.

What type of freeway fits older generations of 2025? We want low stress driving, no traffic jams, plentiful parking, and – when we reach our destination – familiar stores and restaurants. These preferences are habit forming, even addictive. Some believe that high-speed lanes, short commutes, and convenient parking lots should be desired by, and paid for by everyone.

For younger generations it’s a different story. Many (not all) seem to prefer riding bikes and scooters – safely – to their destinations. They want affordable and comfortable public transit along with new food and entertainment options that are walkable. And when they do use a car, they like someone else to drive: an Uber driver. They would rather save money on not building freeways and instead invest in public transit, public places, and an active street life. My generation raised great kids and grandkids, but they don’t love freeways.

When we replaced the Park East freeway the sky did not fall. In fact, everything got better. When we discuss replacing I-794 with a boulevard, many boomers say, “this is very different than Park East – it won’t work this time”. I think they are half right – I-794 is different than Park East, but it won’t be less likely to “work”. The sky will not fall – it will get brighter. Yes, some parts of the freeway network will experience ripple effects, but it is not new. Traffic on freeway shas always increased. The question is how we respond. Replacement of I-794 with a boulevard and street grid system will be a quantum leap better than Park East.

So, what do we do? WisDOT has given Milwaukee freeway choices for “fixing” the short one-mile link between the Marquette Interchange and the lakefront ramps to the Hoan Bridge. The choices range from “doing nothing “to replace in-kind” (meaning the same function but slightly improved), to partial removal with replacement, to full removal.

The best option, in my view, called “removal”, implies, unfortunately, that we would be left with nothing. This is a misleading title. It means full removal of the federally funded concrete travel lanes above grade, but it also means full replacement with more travel lanes on an urban boulevard with an active, effective circulation grid (AKA a well-designed, fully operational, high value, at-grade urban circulation system).

Currently the overhead concrete lanes prohibit the construction of community wealth building. With open land in the highest value place in Wisconsin we can generate life-changing amounts of new public revenue that will support innovative neighborhoods, make better pedestrian places, and expand transit. We can afford to increase vertical housing density, both affordable and luxury housing, supporting a larger, diverse population within walking distance to jobs, restaurants, stores, and favorite places like Summerfest, the Public Market and other venues.

Moving past an older generation’s love of freeways will not be easy. We must preserve our history, respect the urban-suburban balance, and accept the challenge of increasing public revenue with transformational, community-wide wealth. Can cities like Milwaukee really implement such transformations? The answer requires a deeper look at economic value, circulation systems, and neighborhood development.

Economic Value — Let’s Find the Wealth and Spend It Wisely

The public revenue will come from urban development – new and revitalized buildings and their occupants. New revenue is not found on the freeway. Freeways may link places that generate revenue but, by themselves they generate only costs and expenses. Public revenue for cities comes from property tax, sales tax, and disposable income of urban residents. Such revenue grows with more people in buildings, not from more people in cars driving by.

In Milwaukee’s case, new public revenue can grow to billions of dollars. Like all cities, all of this revenue goes into the city’s budgeting process to pay for infrastructure and municipal services. However, the increase in revenue relative to costs (the equivalent of a public “net” revenue) is far greater when high value property combines with high value development and high value jobs. At the same time that the city can garner stronger revenue streams in must also have plans to expend such revenue effectively.

Milwaukee, like many cities, rarely receives increased revenue from the federal government, the state or the surrounding suburbs. Like many cities, especially these that grew in the heyday of Great Lakes industrialization, Milwaukee’s economic sustainability ultimately depends largely on itself. Milwaukee needs new revenues for buildings, infrastructure, and services. Without more revenue there are no added improvements, and this status quo is getting costlier each year. Fulfilling needs and wants requires resources that go beyond the social and human capital of hard work, innovation and talent.

New revenue does not preclude improvements for the general public. In fact, it is the opposite. New revue will allow for bicycle lanes, better transit, lakefront access, affordable housing, jobs, and all of the other needs we have in Milwaukee. This is not a question of “revenue” versus “public needs”. It is a question of “revenue AND public needs” versus “no revenue and no needs”.

Start With The Land and Use It All

From one viewpoint this is a no-brainer: a rebuilt or replaced freeway will cost a lot of money, sandbag use of the highest revenue-generating land in Wisconsin, miss out on a billion in revenue and the new amenities we can create, and simultaneously diminish the appeal and social value of the surrounding areas.

Simply put, two levels of roadways will cost more than one level. An at-grade boulevard will cost a lot less than a fully elevated rebuild. We know, however, from the experience (Park Esat) that freeway demolition and replacement with high quality at-grade streets is far less expensive.

Several analyses of new and past development suggest that over 30 years (the freeway lifespan) we will get upwards of $1 billion (possibly as much as $4 billion) in increased taxes from private development, sales tax from increased business, and more jobs from increased economic activity. The tables in this essay (some developed by the author) portray incremental estimates of public revenues and diagrams showing how, over 30 years, incremental development might grow along the corridor.

The distribution of such revenue must be managed wisely. The private sector – developers, local businesses, financial institutions -- must make a reasonable return on their investments. As long as the revenue “pie” is also shared by the city, local neighborhoods, and the larger metropolitan area. A wise disposition of revenue is clearly possible and almost any outcome will surpass the value of highly truncated (or non-existent revenue “pie”) from full or partial freeway replacement.

Use Development Capacity To Measure Costs, Benefits, & Planning

How big is the potential revenue “pie”? At this time, there are no precise answers but there are several reasonable scenarios to explore. Major public projects always require a complex analysis and the details invariably become confusing. For example, when the State sells land for redevelopment that is a “benefit” to the State, but it may be “cost” to the buyer (like the City). And then the City may sell the land to produce sales and tax benefits as a clear “benefits” to the city but a clear cost to the investors. Put another way, an increase in annual taxes (both property taxes and sales tax) is not labeled usually as a direct “benefit” to the State but it is a positive “impact” for the City.

Often, skepticism about more redevelopment comes from a perception that short-term development risks imply bigger risks the long-term. In practice, short-term market patterns rarely last more than a few years. With Milwaukee’s Park East development, for example, the common critique at the outset was “there is no market – don’t’ tear down a good freeway”. A few years later the critique was “why does it take so long”. Then, a few years later, when Park East was almost finished, there was no congratulatory critique like “wow it really worked, let’s do it again!” But that is exactly what is happening with I-794 – and we should do it again, only bigger and better.

A reliable long-term forecast must use methods different than those found in short-term forecasts for market rate housing. Short-term forecasts use data effectively from the last year or two for a housing and parking estimate but rarely looking out 30 years or more. Long-term projections should use broader trends of social and economic behavior. Think of the stock market with daily and monthly variations versus a decades-long pattern of increase.

We know urban development that replaces freeway works. The added value from freeway replacement must be measured in terms of overall capacity, not the immediate marketplace (the same 30-year long-term metric used for freeway planning). Even now, those who were pessimistic about Park East insist that it was a unique circumstance and not repeatable. The contradiction that the Park East “glass” may became “full” but the “794” glass will be empty is a pessimistic Milwaukee-syndrome: just don’t take a chance; avoid the risk; stay as close to the status quo as possible; and ignore new opportunities as unrealistic. This line of thinking misses the point of Park East. The Park East project was far more successful than we imagined. The future of 794 should be far more positive. Park East was unique. So, to will be 794 if we can only see past the anxiety of change. The age-old carpenter’s adage reminds us: “measure twice and cut once”. In this case when we measure 794 twice, we learn that the value of Park East can be easily surpassed.

Reduce Economic Risk With Phased Investment

Thirty years ago, in 1995, if you tried to forecast the future about Park East, downtown, the lakefront and the Third Ward you would probably have missed all of the following profound economic events:

The nation came to a halt after 9 11.

There were a huge housing crisis and Great Recession after 2008 for several years.

There was a tragic pandemic impacting the whole world.

There have been major political and partisan conflicts that continue to this day

None of these critical market events were predicted in any market analysis. The point is that the immediate development market does not determine the overall long-term development capacity and public value of the Downtown and surrounding areas. Milwaukee’s long-term development capacity is highly favorable due to the following:

Government owned land under I-794 that allows for control of development

Use of a long-term timeframe that will mitigate market peaks and valleys

Well positioned in the natural environment with ample water and lower climate risks.

The undeveloped land (under and abutting the freeway) offers immense value

Local agencies can effectively regulate and reduce risk through local policies.