Measure & Leverage The Value Of Freeway Land — 794

End The Boomer Affair With Urban Freeways — Make Boulevards & Neighborhoods

As a Boomer, I was born into the wonder of freeways. As an architect, I still view freeways as the awesome Roman aqueducts of our time. But as a Milwaukee resident since 1972, I have outgrown my Boomer freeway crush. Today, my generation must respond to changing values for the next generations and plan our city for their future. This matters more than ever, as we design the future of I-794.

What type of freeway fits my older generation in 2025? I like low stress driving, no traffic jams, plentiful parking, and – when I reach my destination – familiar places and friendly people. These preferences are habit forming, even addictive. I am recovering slowly. I still look for good places and people, but I no longer believe that high-speed lanes, short commutes, and convenient parking lots should be developed for everyone.

These three photos show I-794 in the mid and late 1970s. It is worth noting the amount of undeveloped land surrounding the freeway. The same was true of Park East.. Today, while some of the land around I-794 has been developed, after 50+ years the area still did not see the much faster, deliberate pace of development around Park East in 20 years (after demolition). Source: left and center photos from online sites; right photo by the author 1970s.

Younger generations usually tell a different story. Many (not all) seem to prefer riding bikes and scooters – safely – to their destinations. They want affordable and comfortable public transit along with new food and entertainment options that are walkable. They want sustainable neighborhoods. And when they do use a car, they like someone else to drive (like an Uber). They would rather save money on not building freeways and instead support investments in public transit, public places, and an active street life. My generation raised great kids and grandkids, but they don’t love freeways.

When we replace freeways (like the Park East freeway) the sky does not fall. In fact, everything gets better. When we discuss replacing a segment of the I-794 freeway with a boulevard, many boomers say, “this is very different than Park East – it won’t work this time”. They are half right (but not the pessimistic half). I-794 is different than Park East and it will work much better, not worse. The sky will not fall – it will get brighter. Some parts of the freeway network will experience ripple effects, but that is not new. This is not our first traffic rodeo. Traffic on freeways almost always increases over the years. “Will there be jams?” Of course, we always have them, but that is not the right question. The right question is “How will we respond to traffic in the future?” Replacement of I-794 with a boulevard and street grid system will be a quantum leap better than Park East.

So, what do we do? In Milwaukee WisDOT has created freeway choices for “fixing” the short one-mile link between the Marquette Interchange and the lakefront links to the Hoan Bridge. The engineered choices range from (1) “doing nothing”, (2) “to replace in-kind” (meaning the same function but new lanes), to (3) “improvement” (partial removal with replacement), to (4) full “removal” and “replacement” with a boulevard and street grid.

In my view the best option is “removal”, but the name “removal” is misleading. It does not mean we would be left with nothing. The label “removal” is correct freeway jargon for federal naming, but it is not a valid name in the language of urban planners and those who want to fix cities. Freeway “removal” refers only to the federally funded concrete travel lanes above grade which will be removed. However, in the language of urban planning it also means full “replacement” with more travel lanes (for new generations) on an urban boulevard with an active, effective circulation grid (AKA a well-designed, fully operational, high value, at-grade urban circulation system). The language of “replacement” is not simple.

Currently the overhead concrete lanes prohibit the at-grade construction for community wealth-building. With “removal” the City gains open land in the highest value place in Wisconsin. We can generate life-changing amounts of new public revenue that will support innovative neighborhoods, make better pedestrian places, and expand transit. We can afford to increase vertical housing density, both affordable and luxury housing. New high-value housing can support a larger, diverse population downtown within walking distance to jobs, restaurants, stores, and favorite places like Summerfest, the Public Market, Museums and other venues.

Moving past the older generation’s love of freeways will not be easy. Community change creates controversy. In this case. we must preserve our history and accept the challenge of increasing public revenue with transformational, community-wide wealth. This transformation requires a deeper look at economic value, circulation systems, and neighborhood development.

Before Freeways We Had Neighborhoods — Do It Again

Let’s go back to 1910 and look at the maps prepared by the Sanborn Fire Insurance Company. Blocks of streets, lots, and buildings occupied the land that became I-794 in 50 years. Back in 1910 the land was filled with people, places, and activities. A quick count of the parcels indicates that 360 different structures filled the land (see the illustration below). It is no quirk of fate that persons in the insurance business might prepare these maps and look ahead more than a few years to see what risks accrue to the places they are insuring. Today we still do not like to look ahead. We may bemoan the lack of insurance along waterfronts. prone to hurricanes or floods, or areas more likely to experience wildfires. There is no insurance against freeway harms but they can be just as devastating.

This Sanborn map includes streets and blocks from 1910. The top row of blocks corresponds to the blocks currently under I-794 from the Lakefront (on the right edge of the map) to 6th Street (near the left edge of the map). The top street is now Clybourn, the middle street is now St. Paul and the bottom street is now Buffalo. Back then the blocks between toady’s Clybourn and St.Paul (which correspond to the area eventually replaced by I-794) included 360 individual parcels with residential, commercial, and institutional buildings that were part of multiple neighborhoods.. Source: this map was created from the digital map collection at UWM.

What can be destroyed through environmental disasters can also occur as the result of harmful public actions like 1950s urban renewal, redlining, and property takings for infrastructure (like freeways). There is no insurance to avoid the risk of public acts except, perhaps, the use of regulations for property “takings”. In the case of the construction of I-794, property takings, if reimbursed at all, were based on the value at the time of demolition, not the long-term future of the property. This was a major shortcoming. When governments take private property, the price to be reimbursed is the property value at that moment, not the long term value. We assume that the long term loss of public revenue for the land under I-794 has been more than recompensed by the increase in value for all those using the freeway. Put bluntly, we “take” the long term tax revenue (and all other future direct and indirect benefits) from the immediate area and then redistribute big benefits to the wider community (typically the region). The entire City loses all the direct and indirect revenue but surrounding area commuters get the benefit. It is true that we all get to use a freeway to travel further, faster, and safer than in any time in human history. However, what was immensely valuable when the freeway benefits began and the urban neighborhood value was taken away, may no longer be true. It is time to “measure twice” and “rebuild once”.

This image comes from the UWM student scenarios described later in this case study. There are hundreds of feasible options that can be imagined, but they all begin with “removal”. Each student proposal would improve the city and the surrounding area. This master plan was named “The Stitch” by the student team which included Seth Amland, Dulce Carreno, Drake Dahlinghaus, Erik Heisel, Isabelle Jardas, Gordy Russell, and Gabe Zaun

First, Measure Freeway Value

Do Urban Freeways Have A Cost, Opportunity, Asset, Or Liability?

We know for certain that the “free” way is not free. It has a clear cost. But it feels free — we don’t get a monthly bill for freeway service like electricity, heat, cable, internet, water or utilities. If we did get a monthly bill for freeway services you can imagine some of the outcry: “I don’t use that freeway any more, so why should I pay?” It is just like a taxpayer decrying public school costs when that taxpayer has no children enrolled. Or a person in one neighborhood decrying the costs for some other neighborhood’s park, or a suburbanite disgruntled about paying for urban public transit. The general public does not usually appreciate or support indirect or community-wide benefits.

What is not known at the outset of the I-794 freeway planning is who will pay for the freeway (I-794) and how much. Ultimately, each option will have a different price and the bills will go to different public entities. More importantly, all the costs and benefits down the line (after 10, 20, and 50 years) are rarely part of the decision-making equation. Nonetheless., at this point in the decision-making process we cannot be precise about costs but we can make reasonable observations. For example, if the selected freeway option involves building new overhead lanes we know that such a structure will only last a few decades and then require major reconstruction costs, both above grade and at-grade. However, if removed now, we know it will cost less today and will not require reconstructing overhead lanes in 30 years.

But that is still not the key value question. The question, which cannot be answered fully by transportation engineering, is “what does the city get”? This case study is not suggesting that freeway users outside of Milwaukee’s downtown should pay more to replace the current freeway — just the opposite. This essay is suggesting that all parties — urban and suburban —- should pay less for freeways and, at the same time, the value of freeway land can increase the wealth of the communities where the land is located. Measuring the positive impacts of freeway removal requires a completely different lens.

For example, when a transportation agency undertakes an “impact” analysis the assumption is that a freeway (or any new transportation facility) will have a negative impact that needs to be measured and losses need to be mitigated. Unfortunately the “positive” opportunity value of not undertaking a transportation action often gets overlooked precisely because it is not a transportation issue. In some cases, like I-794, transportation agencies might undertake a market analysis to determine short-term value. In the case of a major downtown redevelopment area (like 794) a much broader long-term viewpoint must be used. Moreover, the land under I-794 is probably the most valuable land in the State and along the coastline. While we measure takings based on current value, in this case, we need to measure takings based on long-term future value.

The Basic Value: Measuring Long-term Property Values

Fortunately, in Milwaukee, we have already estimated the value of removing a freeway once before. Milwaukee estimated, planned, removed and redeveloped the Park East freeway land. We measured, but sharply underestimated the potential for positive economic value. The 2002 estimates of new property tax value was approximately $477 million and the final positive outcome was close to $1 billion — twice as high. Moreover, we did not measure jobs, sales tax, or disposable income for the downtown. What can we measure (or at least estimate) in the case of I-794?

How big is the potential revenue “pie”? Usually, there are no precise answers but there are several reasonable scenarios to explore. Major public projects always require a complex analysis and the details invariably become confusing. For example, when the State sells land for redevelopment that is a “benefit” to the State, but it may be “cost” to the buyer (like the City). And then the City may sell the land to produce sales and tax benefits as clear “benefits” to the City but also a clear cost to the investors. Put another way, an increase in annual taxes (both property taxes and sales tax) is not labeled usually as a direct “benefit” to the State but it is a positive “impact” for the City.

Ten year build-out example.

To estimate property values and help visualize periodic growth, the author created a series of diagrams in which the land that could be developed is shown in blue and green tones. The diagram roughly follows the land option created by WisDOT called “removal”. The circles in represent speculative locations for new buildings (10 story apartments occasional parking structures). The pace of development was estimated conservatively at 100 units per year over 30 years. This. yields 3,000 units over three decades — a slow pace of growth and easily absorbed within the land area of and timeframe for the freeway footprint. The 30-year time frame matches a new freeway life-cycle.

Twenty year build-out example

This second diagram shows a possible pattern of building development after 20 years. Some of the development is located on land that was beneath the freeway. Other sites are located on abutting properties which were vacant (except for high-value parking lots) simply because the site remained less valuable adjacent to the freeway. Once the freeway is removed these sites become much more desirable.

Thirty year build-out example

In this third diagram, the area is built out with 3,000 units. The area actually has a far higher capacity and, if it follows the path of Park East development, represents a reasonable pattern of growth and value. Many options are possible. The key is providing an open palette that will attract different developers, investors, businesses and designers.

Base property value estimates over 30 years

The estimate suggests that, conservatively, the property taxes collected will be close to $.5 billion. For the “replace-in-kind” option it is reasonable to assume that the value of new taxes would be $0 and for “partial improvement” approximately $.1 billion (not shown).

Measure The Big Secondary Windfalls: Disposable Income, Jobs, Sales Tax

Secondary Benefits - Sales Tax & Disposable Income

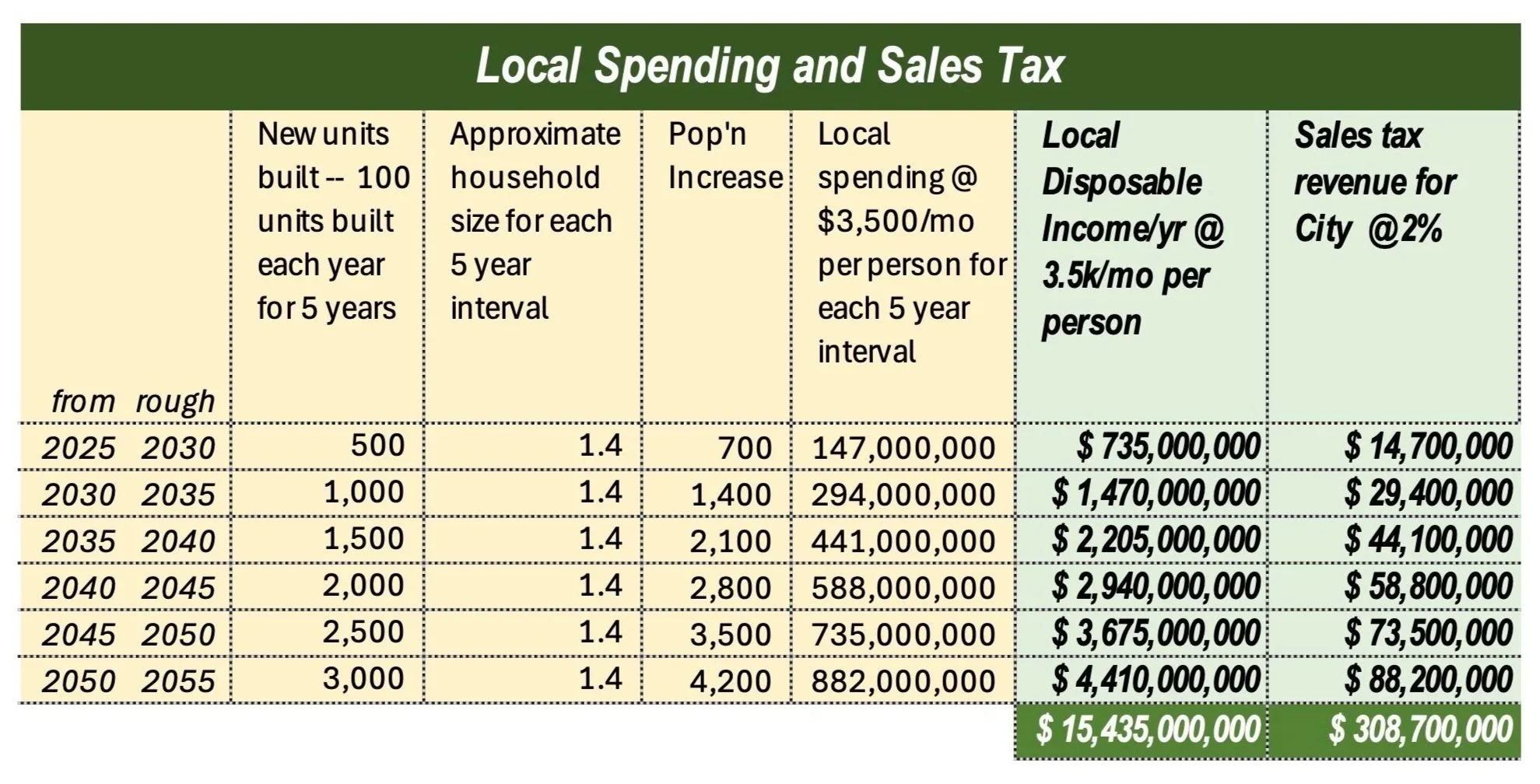

In urban planning, the measurement of land development value often stops with property. However, the bigger economic boost is actually indirect. It comes from the economic activity of the inhabitants — people, not property, who live and work in the city. This table estimates, conservatively, the 30-year sales tax benefit at about $.3 billion and the local disposable income at about $15 billion. The other freeway options, as noted previously produce substantially lower benefits.

Secondary Benefits - Jobs in Construction, operation & Maintenance

New construction always yields more jobs. But the types of jobs vary. Freeway construction jobs are well paid, but charged to taxpayers and relatively short-term. For new buildings, the construction jobs are paid by private investors and, more importantly, the buildings require longer, full-time jobs for operation and maintenance. The table to the left shows the huge value obtained in local, private sector jobs (close to $1 billion) linked to freeway “removal” as opposed to the public cost of freeway-related jobs.

Measure The Capacity For New Buildings

Great cities evolve over decades. Milwaukee already has growing, attractive neighborhoods in downtown and nearby. These City centers and nearby districts experience peaks and valleys but, like the stock market, they exhibit a long-term upward trajectory. Every year new buildings fill up, some quickly, and others take longer – but sooner or later they are all occupied. Young and old, boomers and zoomers, like to live near restaurants and entertainment, and especially Lake Michigan.

Often, skepticism about redevelopment comes from a perception that short-term change is risky and undesirable. In practice, short-term market patterns rarely last more than a few years. With Milwaukee’s Park East development, for example, the common critique at the outset was “there is no market – don’t’ tear down a good freeway”. A few years later the critique was “why does it take so long”. Then, a few years later, when Park East was almost finished, there was no congratulatory critique like “wow it really worked, let’s do it again!” But that is exactly what is happening with I-794. We should repeat Park East, only bigger and better. Instead we hear the same false economic arguments and fear of change.

The development capacity that can replace I-794 occurs in the center of the city, not on the urban fringe (where capacity is often overestimated). The I-794 corridor is “smack in the middle”, the hottest point of value. It has always seemed ironic that the most expensive real estate in Wisconsin (historically under the US Bank, now Baird, building) sat across the street from open land in parking lots under a freeway with no property value. There is no shortage of value under I-794 – it just requires us to open it up, plan it, phase it effectively (so we minimize risks), and let the market unfold in a fair, equitable, long-term manner.

A reliable long-term forecast must use methods different than those found in short-term forecasts for market rate housing. Short-term forecasts use data effectively from the last year or two for a housing and parking estimate but rarely look out 30 years or more. Long-term projections should use broader trends of social and economic behavior. As noted, think of the stock market with daily and monthly variations versus a decades-long pattern of increase. The City needs to regain its land under the freeway and hold it for long term value.

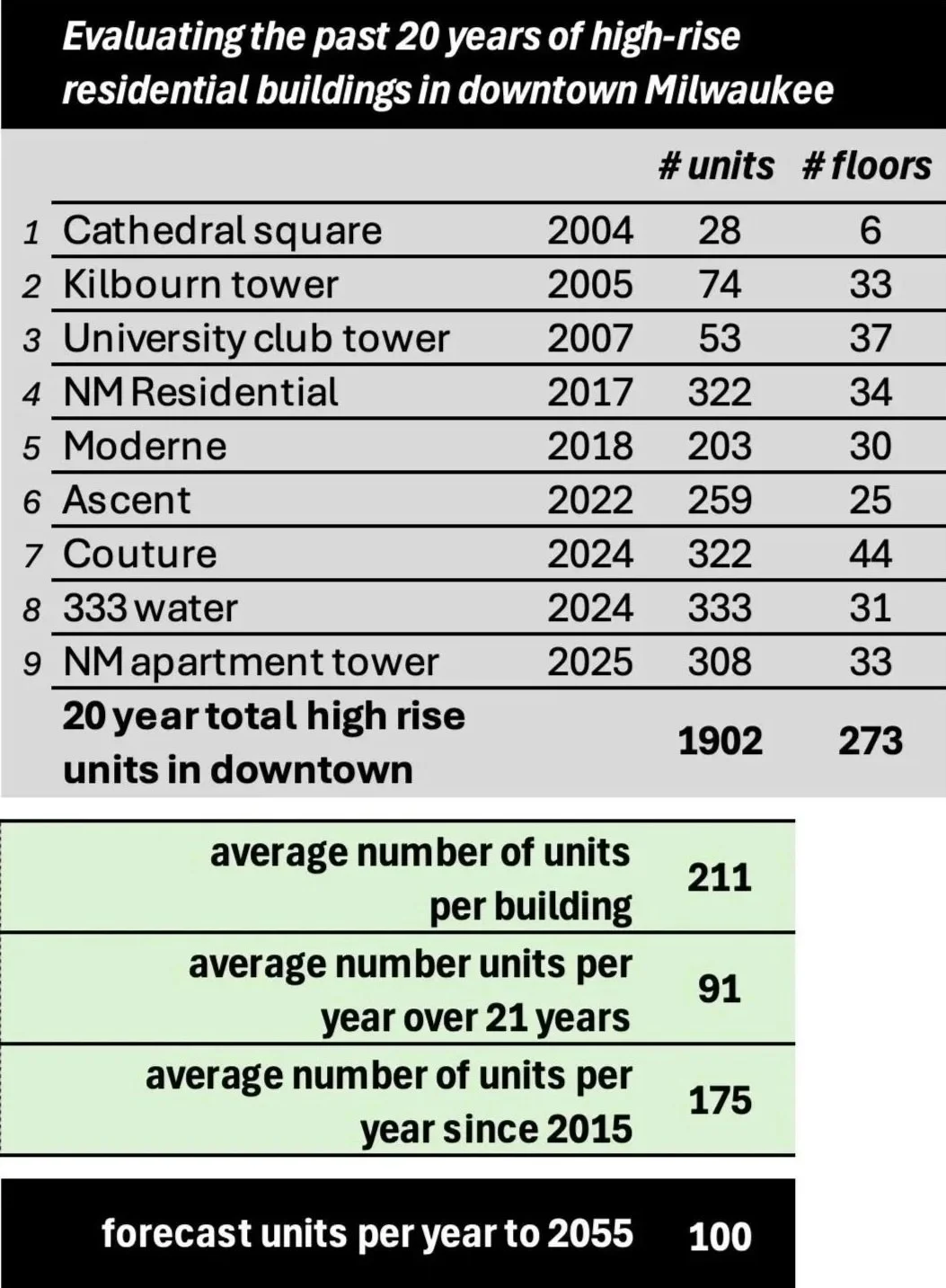

Estimating Increasing Development Capacity

City center buildings are getting bigger and more frequent. Risks are going down, not up. There is a major difference between (a) the losses experienced by investors who build too soon or too late and (b) the long term rewards of long-term holdings of new development. This table shows how new downtown residential structures have increased over the last 20 years. New buildings are getting taller with more units. Estimating development capacity based on land potential is a common, effective method in contemporary planning but, as yet, is not as popular with urban planners in the U.S.A.

High-rise buildings have been added to downtown Milwaukee (and most cities world-wide) since the 1960s and follow a traditional pattern found along waterfronts and downtown centers. The increase in high-rise buildings in downtown Milwaukee seems to have entered is transformational shift in the early 2010s, right after the Great Recession. If this shift continues this study’s estimate of 3,000 units over 30 years is quite low. Some of the student scenarios discussed later project 6,000 or more units. Overall, a modest mid-range estimate with 3,000 units (100 per year for 30 years) seems to be a useful, and a conservative starting point.

We know that replacing freeways with urban development works for cities and their metropolitan surroundings. The added value from freeway replacement should be measured in terms of overall capacity, not the immediate marketplace (the same 30-year long-term metric used for freeway planning). Even now, those who were pessimistic about Park East insist that it was a unique circumstance and not repeatable. Is the “glass half empty or half full”? The view that the Park East “glass may seem full” but the “794 glass will be empty” is a pessimistic Milwaukee-syndrome: just don’t take a chance; avoid the risk; stay as close to the status quo as possible; and ignore new opportunities as unrealistic. This line of thinking, with a virtual blindfold, misses the point of Park East. The Park East project was far more successful than we imagined. The future of 794 should be even more positive. Park East was unique. So too will be 794 if we can only see past our fear of change. The age-old carpenter’s adage reminds us: “measure twice and cut once”. In this case when we measure 794 value twice, we learn that the value of Park East can be easily surpassed.

Lower The Risk: Phase Development, Avoid Reconstruction

For decades user groups north and south of the freeway have lived with the debilitating nature of freeway structures, as well as the knots and clogs due to a geometrical chaos of ramps, exits, entrances, turn lanes, one-way traffic, and necessarily complex signalization systems. The old photos of land around I-794 show land parcels that never developed while almost all the empty parcels, in less desirable locations around Park East, have grown.

Thirty years ago, in 1995, if you tried to forecast the future about Park East, downtown, the lakefront and the Third Ward you would probably have missed all of the following profound economic events since that time:

The nation came to a halt after 9 11.

There were a huge housing crisis and Great Recession after 2008 for several years.

There was a tragic pandemic impacting the whole world.

There have been major political and partisan conflicts that continue to this day

None of these critical market events were predicted in any market analysis for urban downtowns and city centers. The point is that the immediate development market does not determine the overall long-term development capacity and public value of the Downtown and surrounding areas. In the future the risk comes from rebuilding the freeway (in part or completely) while the reward comes from removing it. A poor solution copied and updated is still a poor solution. In contrast, full removal with a boulevard replacement and updated street grid will offer new rewards and opportunities. A new boulevard-based system will cut maintenance costs since we will only be paying for one level of streets rather than two levels (one on the ground and one more expensive level in the air). Also, with a street grid system, incremental changes are far easier to plan, adapt, manage, and revise as needed. Along with these advantages Milwaukee’s long-term development capacity is highly favorable due to the following:

Government owned land under I-794 allows for control of development and substantial transition parking

Use of a long-term timeframe will mitigate market peaks and valleys

Great location with natural environmental features, ample water and lower climate risks.

Undeveloped land (under and abutting the freeway) offers immense value once demolition is announced.

Local agencies can effectively regulate and further reduce risk through local policies.

The cost of maintaining an elevated freeway infrastructure (paid by the State) would be far less if the freeway lanes are removed.

Maintenance of the-grade infrastructure (paid by the City) would be about the same and new taxable buildings will provide revenue for maintenance.

The key point is that long-term phased development requires a different yardstick to measure costs and benefits. If we accept reduced risk and lower annual costs, then the long-term investment question becomes: “Can we spend added revenue wisely”?

Leverage Freeway Land To Create & Spread Wealth

Considerable public revenue will come from new urban development, revitalized buildings and their occupants. Freeways link places that generate revenue but, by themselves they generate only costs and expenses. Public revenue for cities comes from property tax, sales tax, and disposable income of urban residents. Such revenue grows with more people in buildings, not from more people in cars driving by.

In Milwaukee’s case, new public revenue can grow to billions of dollars. Like all cities, all of this revenue goes into the city’s budgeting process to pay for infrastructure and municipal services. However, the net increase in revenue relative to costs is far greater when high value property combines with high value development and high value jobs. At the same time the city garners stronger revenue streams it should also have plans to expend such revenue wisely.

Like many cities, especially those that grew in the heyday of Great Lakes industrialization, Milwaukee’s economic sustainability depended largely on itself. Today, Milwaukee needs new revenues for civic buildings, infrastructure, and services. Without more net revenue there are no net improvements, and the status quo is getting costlier each year. Fulfilling needs and wants requires resources that go beyond the social and human capital of hard work, innovation and talent. New revenue will allow not only for better circulation networks (bicycle lanes, transit, lakefront access) but also affordable housing, jobs, and other critical needs. This is not a question of “gain revenue” versus “address public needs”. It is a question of (1) gain revenue AND address public needs with freeway removal versus (2) no revenue gains and no needs addressed with the freeway rebuilt in whole or in part.

From one viewpoint this is a no-brainer: a rebuilt or replaced freeway will (1) cost a lot of money, (2) give up new net revenue from the highest revenue-generating land in Wisconsin and, (3) simultaneously, diminish the value of the surrounding areas. Analysis of new and past development suggest that over 30 years (the freeway lifespan) we will get upwards of $1 billion (possibly as much as $4 billion) in increased taxes from private development, sales tax from increased business, and more jobs from increased economic activity. The tables in this essay (some developed by the author) portray incremental estimates of public revenues and diagrams showing how, over 30 years, incremental development might grow along the corridor.

The distribution of new net revenue must be managed wisely. The private sector – developers, local businesses, financial institutions -- must make a reasonable return on their investments. At the same time, the revenue “pie” should be shared with the city, local neighborhoods, and the larger metropolitan area. A wise disposition of revenue is clearly possible and almost any outcome will surpass the value of highly truncated (or non-existent revenue “pie”) from full or partial freeway replacement. As previously noted the revenue estimates were based on a forecast 3,000 new residential units over 30 years. A less conservative estimate might be 6,000 units or even higher as shown in student studies.

Removal Creates One Plan With Hundreds Of Options

The I-794 spur was built in the 1960s at a time when the Third Ward was filled with train tracks, Summerfest was in its infancy, and plans were set to tear down historic buildings for new industry. Back then no one thought of the Third Ward as a powerhouse district – no one except a few visionaries. And I-794 was not seen as a “divisive” piece of infrastructure because there was not much to divide. Today, a half century later, the whole area has grown into a spectacular neighborhood. I-794 has become divisive due to growth of the City around it. Now the land needs to grow again.

Since the 1970s many transformations have occurred – they are hard to notice since they happen slowly, but they are very real. The Menomonee Valley with Harley and Potawatomi is part of this slow but inevitable transformation. The Northwestern Mutual campus is now a reality. Even with the pandemic and Great Recession new high rises have emerged. Now I-794 is not at the edge of the growth zone – it is at the very center of four major transformative districts, and it is time for reconsideration of its value and its future. Such optimism is not a case of “if we build it, they will come”. These student ideas do not rely on dreams — they are not “academic” nor “infeasible”.

The I-794 land is at the heart, the point of highest value, the place of greatest potential attraction that will extend, expand, leverage, revive, engage, and stimulate the city that is already here. This area will not remain an example of a Jane Jacobs “border vacuum”. In fact, the student scenarios below are NOT a single plan — they are many overlapping plans which, over time, might inform and inspire different combinations or outcomes. From the perspective of urban redevelopment, there is not one “full removal” plan but hundreds of possible plans. These scenarios are the starting point, not the conclusion. Many design and development realities should be explored, especially in terms of adding net revenue for community-wide neighborhoods, region wide environmental improvements, and districts that will be impacted positively by this project.

In denser cities a neighborhood could be 500 units on one or two blocks. In older traditional suburbs (such as Wauwatosa, Shorewood, South Milwaukee) a neighborhood could be just 300 units spread across ten blocks. Jane Jacobs pointed out that neighborhoods do not have definitive boundaries like political jurisdictions. They grow, shift, and change over time. Milwaukee’s Bay View was defined as a small neighborhood until realtors spread the name to expand it as a new branded market. In the Park East project, at least two new neighborhoods emerged, along with a new grocery store, more restaurants, and cafes. New neighborhoods that replace I-794 will grow, combine, overlap and change our community in positive ways for decades.

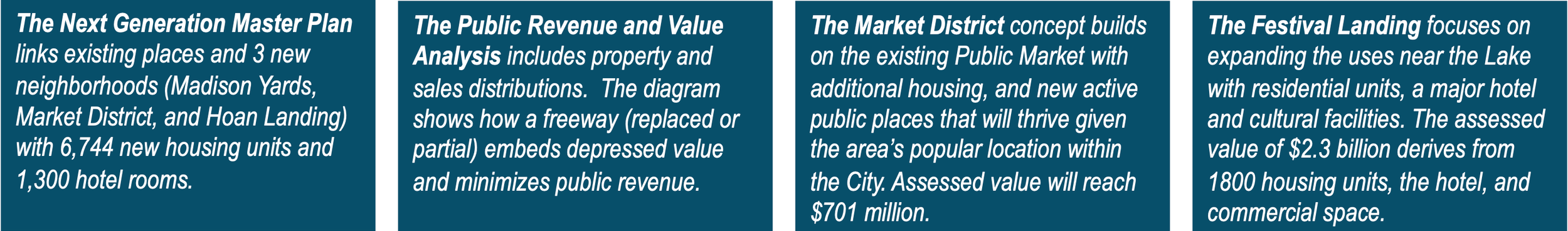

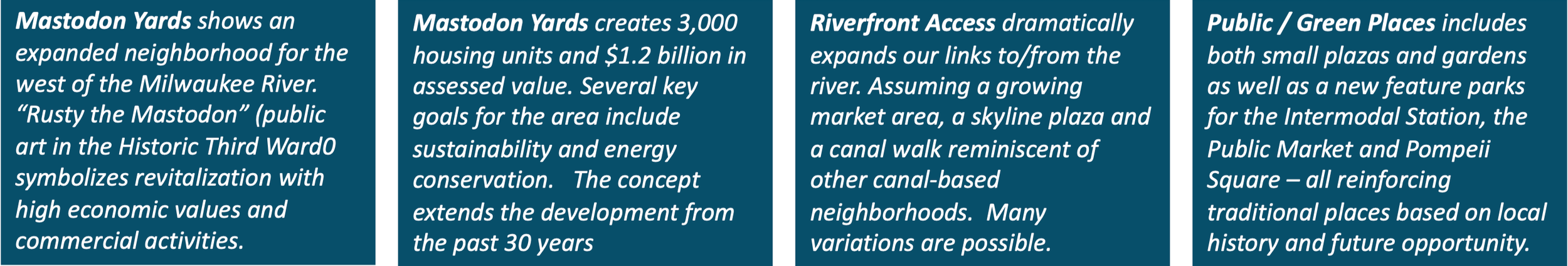

The site plan above shows detailed redevelopment blocks (as defined by WisDOT’s “removal” plan with blue, green and yellow) areas that are brought to life in the student proposals. The redevelopment proposals address the needs and opportunities of existing property owners, residents, and businesses. With an at-grade boulevard system, access to/from local places – especially multimodal access -- will be better. Newly emerging uses, like the Fox Town Brewery, dog park, and public art will be respected and incorporated into new plans. Vacant and underutilized parcels surrounding the corridor which have languished due to the negative impact of the freeway will be revalued much higher.

UWM Scenarios

In spring 2025 a class of 14 students at the UWM (University Wisconsin – Milwaukee) conceptualized, in detail, the development of new neighborhoods replacing I-794. Under the guidance of UWM faculty – Carolyn Esswein and Larry Witzling – these students proposed transformative social and cultural places using a new, at-grade boulevard and “best practice” circulation systems. These new urban neighborhoods serve multiple population groups, expand income diversity, support a wide range of housing types, engaging urban places, and make Milwaukee a compelling destination on the Great Lakes. In the students scenarios 3,000 to 6,000 new housing units represent about three or four new neighborhoods or districts, typical of Milwaukee. Such neighborhoods represent a vibrant mixture of places, thriving areas with both high rise and small scale buildings, affordable and luxury housing, along with restaurants representing national franchises as well as local entrepreneurs.

The following illustrations show opportunities, not finished plans. That is the point of selecting the removal freeway option. We need opportunities for the future, not auto lanes that that embed us in concrete for another 30. years. No one knew before-hand how Park East would grow. When we started redeveloping the lakefront at O’Donnell Park no one knew the Art Museum would expand or that other institutions would arrive. The community created opportunities that acted like managers and the concepts emerged. That will happen again if we remove the freeway, but not if we replace-it “in-kind” or reconstruct the same barriers under the misleading labels of “improvement” for cars.

We asked UWM students (seniors and graduate students) to focus on the “removal” option and see what they could imagine for the future of their generation over the next 30 years. They produced feasible concepts — concepts that can be implemented. There are two sets of concepts illustrated below that correspond to the two student teams that combined their work over the course of one semester. Readers can zoom in to the illustration for more details. These details may look like the “end of a maze” but they really hypothesize a beginning. Nothing, however, can begin if we do not remove the freeway. Put another way we cannot build for the future if we do not first rethink what we did in the past.

New places and neighborhoods, like the ones portrayed by the students, will grow incrementally over 30 years. Growth on new land begins in small projects at the onset of post-freeway investment. Over time, projects ramp up rapidly (like the Park East announcement followed by Riverfront housing, Moderne, Fiserv, the Public Museum, MSOE expansion, and multiple developments). The 794 corridor offers a much larger transformational opportunity that goes beyond current models. Each of the student projects foresees new development will that add a completely new dimension to Milwaukee. Thirty years ago, we did not have a Brewery District, Deer District, Northwestern Mutual Campus, or even the Harley Davidson Museum. When plans for these districts began people were doubtful, they would succeed. No one reports that the pessimists were wrong, but all the planners remember the skeptics “Who will want to live there? Where will so many people come from? It just can’/t work?” And then it happens.

The Next Generation Team — “Neighborhoods, Networks, & Next Generations ”

These 12 illustrations (or “boards”) in three rows of design “boards” were by the developed by the “Next Generation” team. The student members of this team (in alphabetical order) included Molly Burns, Mike Burrows, Colin Flanner, Luke Koelsach, Isabella Lemieux, Shane O’Neil, and Carl Sveen

The Stitch Team — “Stitches, Seams, & Synchronicity”

The Stitch Team, like the Next Generation proposal, created an overall master plan as well as four distinct neighborhoods. The team name implies their purpose and method: stitch together the disconnected places that have been isolated for over 50 years, and create “seams” that allow different areas to reconnect. Over time, uses and activities create kind “synchronicity” of experience — a hallmark of thriving urban communities.These 12 illustrations (or “boards”) in three rows of design “boards” were by the developed by the “Stitch” team. The student members of this team (in alphabetical order) included Seth Amland, Dulce Carreno, Drake Dahlinghaus, Erik Heisel, Isabelle Jardas, Gordy Russell, and Gabe Zaun.

Make A Better Circulation System, Not Just Better Lanes

What’s Wrong With Replacing A Freeway “In-Kind” Or With “Improvement”?

Everyone has heard “if it’s not broken don’t’ fix it!” Well, in this case it is broken – the freeway, the circulation network, and the urban places on the ground. The freeway is at the end of its useful life and needs major improvement. If we simply reconfigure the existing freeway to make it more efficient, then we still have an above-grade structure splitting Downtown and the Third Ward – socially, visually and economically. And it will be broken again and again. Jane Jacobs called such major infrastructure barriers “border vacuums” because they depress all adjacent activity and value –a complete vacuum devoid of significant social or economic use. Someone pointed out that repeating the same mistake over and over is a definition of mental illness. This is the fourth time transportation planners are trying to fix this stretch of freeway. It’s time to stop and just remove it.

Two-thirds of the current drivers on 794 simply get off and on downtown – for them removal, with a replacement boulevard and street system, will be faster. We will still have an efficient road “lifeline” with a well-designed one-mile cross-town boulevard. Traffic still works, it is just different. Crosstown drivers experience little loss in value compared to the huge lost value of a disconnected urban center. Replacing the Park East freeway led to balanced traffic. There were no post-construction complaints about travel time, and urban development that produced great benefits. In fact, the pessimists who predicted economic disaster (“no suburban shoppers will come downtown”) were completely wrong — not just a little, but big time. Replacement of 794 should lead to an even better success story. We need the best version of a balanced solution. As proved by the student projects, “full removal” is not just one community-wide option. There are many ways to replace I-794 and then rebalance and reconfigure the entire circulation system for this area. It needs to be done carefully to be effective.

Today freeway repair and replacement is so commonplace that WisDOT devotes a website to help drivers understand the never-ending process of rebuilding portions of freeways every year. In any case, reconstruction for DOT’s “replace-in-kind” and “improvement” alternative will create huge snarls perhaps worse than “removal”. With all options, there will be confusion and delays for two or more years. Once construction is completed, for all options, most drivers feel some relief and rarely recall past performance problems. We have not heard, for example, any indicators that the Park East driving conditions resulted in the traffic “nightmares” predicted by those who feared freeway removal. Likewise, other cities do not report significant traffic complaints after freeway removals.

WisDOT has measured some travel times in detail, focused primarily on peak times. Key issues are ripple effects, the lift bridge, on and off ramps, and overall traffic diversion. In many cases the times are comparable. There are some spots where DOT predicts lower levels of service. Many of these spots can be mitigated if needed and many of the problems are common within our system. We can assume many people will use a variety of routes with any of the current freeway options and local street options and that chronic slowdowns can be mitigated. In addition, these estimates are based only on driving time on the freeway. When we consider other benefits across the network for parking, bicycling, and walking the added drive times may seem a reasonable balance for all parties.

The dotted red line depicts the official WisDOT I-794 area for freeway changes. From the viewpoint of a circulation network it is critical to consider all forms of movements including freeway intersections as well as all at-grade vehicular movements, pedestrian crossings, pedestrian quality, bicycles, parking, signage, signalization and so forth. While freeway traffic flow might work best with portions of the other options, comprehensive patterns of circulation for this area will, from an urban planning perspective, work better in the “full removal” option. This graphic was downloaded from WisDOT project website.

Use Street Grids To Balance Circulation

Instead of viewing “freeway replacement” with anger, fear and disbelief we must see it as a transformational opportunity. The questions go far beyond issues of travel time. We need to know how replacement options will help (or harm) existing businesses and new redevelopment. How might it work for pedestrians, bicyclists and others? What will it look like? Will it be confusing and stressful? In urban places, especially downtowns, an at-grade street system, especially with a boulevard on Clybourn, will be the best option for access, circulation, and a positive driving experience.

Traffic statistics that show increased driving times on freeways and so-called levels of service. These statistics create misleading pictures of overall circulation throughout a metropolitan area. They also do not show the stress that always accompanies freeway movement in urban areas. Origin-destination driving statistics fail to incorporate changes in walking times and parking convenience. Also peak driving behaviors change frequently over the course of freeway usage — dome drivers shift their driving times, others use transit, many do not even realize the increase, and some complain regardless of the conditions. It is worth noting, again, that after the Park East freeway was removed there were no complaints from the drivers of the 40,000 cars that added drive time but also added convenience and lower stress. The point here is that the measurement of driving times is a poor basis for major decision-making options in urban areas.

Moreover, a boulevard and street grid actually provides a better overall or comprehensive outcome – not “split” between “freeway versus city” but balanced and shared between the needs of suburban and urban communities. With full at-grade replacement all drivers still get where they want to, and all pedestrians have more destinations available along with a much-improved downtown destination. People who do not like an urban downtown (including many who pass through downtown on I-794 today) always have the option to bypass the urban area entirely. Using the other freeways and arterials. On the other side of this attitude, those who want to engage in “city life” (both current and future generations) will have destination-quality activities they can appreciate.

The author’s diagram of the street grid shows how many points of traffic movement that will be available if the freeway is removed. As the project unfolds minor changes occur, but the basic idea of slower, safer and “free-flow” traffic still represents a huge improvement for drivers.

Street grids have provided the most effective and efficient approach to city circulation and development for several centuries. They are not a new idea. Some of our most popular urban neighborhoods were laid out long before cars were invented. This includes Milwaukee and many of our older urban suburbs. Grids are adaptable, flexible, easy to navigate and more sustainable. Grids facilitate a wider range of “multimodal” circulation needs, especially for pedestrians. WisDOT, for example, is able to identify some important pedestrian parameters all of which will be improved greatly if the freeway is replaced with a boulevard and better street system where walking and bicycling replaces driving

1 in 5 residents walk to work now.

Over 4,000 pedestrians and bicyclists cross St. Paul Avenue and Broadway.

About 1,000 pedestrians cross daily Clybourn and Van Buren.

Based on this data and related findings it seems increasingly important to consider a “Pedestrian Level of Service “(PLOS) as equally important to a Vehicular Level of Service (VLOS). For example, using the author’s projected increase in development, population groups and neighborhoods it is feasible to construct an estimate of detailed pedestrian traffic based on new job locations, local retail goods and services, and related items. If WisDOT or some other public agency allocated an equivalent level of resources to such a study, then we might see the estimated pedestrian traffic increase a hundredfold or more. More importantly, every pedestrian “trip” without a car implies one less trip in all of the traffic counts. Unfortunately, statistics on combined walking and driving trips are not part of this, or other freeway studies. Nonetheless the author and others have developed and applied subjective criteria that should contribute to evaluating the street grid and its level of pedestrian service (none of which are included in the DOT’s latest metrics):

Walkability with pedestrian prioritization, protection, ease of crossing, ease of two-pedestrian movement, microclimate protection and modifiers

Street definition with strong corners, continuity along block faces, layered facades, entries per street face

Visual harmony and diversity with multiple lots per block-face, lot widths that fit the context, changes in building height and massing

Visual depth between interior and exterior places, frequent entries

Maintenance that is comprehensive, daily, seasonal, private/public

Overall quality including detail, materiality, authenticity, installation, visual appeal of pedestrian movement

Comprehensive Safety for drivers, pedestrians and bicyclists

Origin-destination times for trips within and between local activities (not just freeway trips)

Reduction in confusion and stress for pedestrians and others

Parking management (including on-street, surface lots, structures, costs

The point of these criteria is that a freeway is not a stand-alone, independent system. In contrast, an at-grade boulevard circulation network is, by definition intended to be measured as an interdependent, not isolated, system. Vehicular, pedestrian and all the other components of multi-modal circulation support each other in a complex system. Maximizing one system component at the expense of the other components becomes problematic and counterproductive. An at-grade system allows for a more thoughtful and effective process. Opening and closing streets in small increments minimizes, rather than expands, then extent of individual circulation disruptions. Whether we slow down for freeway on/off ramps or we slow down for a boulevard, the real test comes in the flexibility and appeal of the rest of the circulation system. A boulevard-based circulation system is far more flexible and adaptable to the changing patterns of movement and development in dense urban areas (but not in suburban or rural areas).

Based on the latest DOT metrics, for downtown workers, the situation with the boulevard gets better for many and a bit slower for others. The major intersection snarls at the lakefront have disappeared. Drivers, in the boulevard scenario, make fewer turns and hit fewer traffic lights if they leave the turn on/off the boulevard closer to their destination. The same issues arose with the Park East freeway removal – the grid made it easier for most drivers to get to their local destinations a bit faster.

Expanded Transit And Bike Lanes Make a Difference

With a boulevard and improved grid system, transit and bicycle circulation will also improve with more routes, better access, more convenience to users and less need for personal vehicles. This will not happen immediately but evolve incrementally. In many cities, newly proposed public transit systems aroused negative responses by people who viewed public transit as supporting population groups they viewed as undesirable. Sometimes these attitudes were based on underlying racial and economic discrimination. In many cases, however, opposition to public transit comes from the non-users — the people who do not view transit as a community-wide benefit and therefore do not think they should help pay for it. The same people, however, do see freeways as a community-wide necessity that should be financed by everyone, even those who do not use it directly.

Inn the long-term, transit actually helps freeway users — as more people use transit they use cars less frequently. As more people live in denser downtowns, fewer live in suburbs. The same is true for urban density — the more people desire and choose to live downtown, the less pressure there is to expand housing in suburbs. Better downtown urbanization helps suburbs in the long run, but it does not happen overnight.

Over time fewer commuters (especially younger generations) will use cars.

Bike lanes and routes that already have had an impact, will grow stronger.

Improving regional passenger rail can be a big game changer.

New BRT lines can be implemented to carry more people to jobs and take cars off freeways.

Freeway bus routes that bypass downtown can now stop on Clybourn and become part of the solution.

All multimodal choices will grow (not diminish) as new generations of residents and workers adopt lifestyles that decrease use of cars (this has happened across Europe and in North American cities with similar characteristics).

Resolve Circulation Details And Mitigate Weaknesses

Many designers have seen the phrase attributed to Mies van der Rohe’: “God is in the details.” In recent years it has been restated as “the devil is in the details.” They are both true, especially in urban planning. Every complex urban design project contains unique details which must be resolved in order to make the entire project feasible and successful – I-794 is no exception. Here are some of the details that need special attention to make a “full removal” freeway options more successful:

The site plan above — the “removal” option from WisDOT — shows numbers corresponding to locations in which urban design details need to be addressed: (1) the Hoan Bridge on/off intersections, (2) the Lift Bridge on Clybourn, (3) Cultural Facilities and the Gateway Plaza, (4) the Summerfest area, (5) the Third Ward area, (6) the Riverfront (with the Dog Park and FoxTown) and (7) the Intermodal Station.

In any major transportation project there are always major components of the context which require special design attention and resolution. Such elements are not typically part of the mission, jurisdictional scope or expertise of the transportation consultants. In the I-794 project some of these critical contextual elements are shown in the diagram above and others described below:

The Hoan Bridge. The Hoan Bridge remains in all options. It stays where it is, with reconfiguration of on/off ramps to fit the modifications on the ground. However, with a new boulevard, the number of connections to/from the Hoan increases and allows traffic to be dispersed more effectively with less stress and much less confusion.

Traffic Diversion and Commuting. As plans move forward The Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT) estimates the changes in traffic movements across a wide swath of the freeway network at peak hours, including on and off ramps. Their estimates show likely locations (1) when traffic will flow smoothly as well as (2) points of high traffic congestion if nothing else is done to resolve the problem. When viewed, however, by most observers it looks as if intersections with “low levels of service” are inevitable — they are not inevitable and do not require freeways to resolve the problem. Mitigating detailed issues depends primarily on actions from other agencies including the City, County and Region. Put simply, Milwaukee can resolve diversion and commuting issues, one at a time, to minimize the negative impacts of full removal.

Passenger and commuter rail. Milwaukee’s Intermodal Station is a “beginning”. The community needs a better system of commuter and passenger rail. Several studies in the past have been cut short. New efforts may result in a feasible, politically supported commuter/passenger rail improvements. In the case of I-794 rail improvements should be coupled with replacement of the current main post office. If this occurs, the area would experience major redevelopment over time with new activity generators, links to a canal walk, tourism and housing. If a new boulevard and street grid occurs, such options should be recognized and embedded in the new plan

Cultural Facilities. In the last three decades the use of the lakefront for major cultural facilities has expanded with the Milwaukee Art Museum addition, Discovery World, the Betty Brinn Children’s Museum and, most recently, proposals for a Gateway Plaza. Growth will be more successful if the at-grade boulevard and street grid were implemented along with a new, enhanced, pedestrian and bicycle system that create strong lakefront continuity from the Veterans Park to the south end of Summerfest and the Third Ward.

Major Events/Venues. As Milwaukee’s most renown lakefront development in the last 50 years, Summerfest presents multiple needs in terms of circulation and operation. In this case the at-grade option includes multiple intersections providing access and a much-expanded opportunity for surface parking (especially during the first phase of development). Long-term development also allows for expansion of Summerfest activities. Daily traffic and event traffic can be reconfigured easily and fully accommodated with a better grid system and multiple circulation options. Over time Summerfest, as a leading “entertainment” management enterprise might expand on the new land that is easily accessed to the west.

Lift Bridge. The problem of bridge “lifts” exists in many cities. Typically it is resolved through a combination of innovative engineering and revised policies and regulations. Today, bridge lifts on local streets are required for commercial boats. WisDOT, however, is not the agency that would take actions to mitigate this issue. Although WisDOT can take actions like buying property for a right-of-way, it does not have regulatory authority for all bridge lifts. In this case the problems caused by bridge lifts on Clybourn are not inevitable but they do require assertive action by other government agencies.

Riverfronts. Many freeways cross rivers. In this case, I-794 crosses at the location of the new Dog Park and the FoxTown enterprise. With a removed freeway both of these efforts, as well as new, compatible projects, could expand and be even more successful. Over time, both sides of the Milwaukee River can be equally active.

District Circulation. When freeways come down there is always a prediction of massive traffic tie-ups. It is usually the opposite case with improved grids that relieve the congestion. Local property owners and businesses frequently see any traffic changes as a challenge — In this case the fear is congestion in the Third Ward. All plans for I-794 – whether it is at-grade or elevated – will require readjustment of existing streets and intersections. The speculation that an at-grade solution will create an imbalance and add traffic to the area, With a grid system rebalances easily. The traffic slows down comfortably, pedestrian movement increases, more people use transit, and more business opportunities arise. The history of the Third Ward from its rebirth in the 70s until today is testament to the ability to adapt and thrive.

Freight Traffic. Freeways usually link to major freight moving areas — airports, waterfronts, industrial areas. In Milwaukee I-794 links freight traffic to the Port of Milwaukee. Bay Street, a critical truck route linking I-94 and the Port, is underutilized and can handle more truck traffic without significant delays. While most of Bay Street is bordered by non-residential uses, there are, however, homes abutting Bay Street that would benefit from noise reduction actions including regulations for trucks, better technologies, and subsidized sound mitigation improvements.

Implement Generational Transformation

The Hoan Bridge is Milwaukee’s gateway landmark. It symbolizes the strength of the City and its place on the Great Lakes. It also represents how an earlier generation recognized and implemented a major change for future generations. Photo by author 1973

Transform Freeway Land (Slowly) Into Next Generation Neighborhoods

As of this writing (November 2025) WisDOT continues to study options for repairing and/or replacing I-794. Revised options will be evaluated through 2026. At the end of the process, with full community input, one alternative will be recommended. From a planner’s perspective the creation of an at-grade boulevard, new grid-based circulation system, and transformational neighborhoods could and should contribute to Milwaukee’s future.

All of the freeway projects noted in these essays unfold over a longer time period, often with many ups and downs along the way. Several of the other freeway projects have been located in smaller scale, less dense residential neighborhoods. Park East was the key exception, and the results clearly show spectacular positive outcomes. A replacement for I-794 will be stronger and better because it has more locational amenities than Park East – especially proximity to Lake Michigan, transit, cultural activities, and entertainment. If we do not embrace this once-in-a-generation opportunity, we will spend hundreds of millions fixing a freeway that will need replacement in another 30 years. Hopefully we can replace it now.

Look Forward & Replace 794 With “Opportunity” – it only knocks once

A transformational opportunity has knocked on Milwaukee’s door. It’s called the 794 “removal” plan from WisDOT. It’s a big opportunity to create new neighborhoods, gain a windfall of public revenue, and develop a comprehensive circulation system. For 50 years this opportunity was covered under the 794 freeway. It’s time to open it up.

The one-mile stretch of the 794 downtown freeway has deteriorated. It solved yesterday’s problems, not tomorrow’s challenges. We should replace this stretch of freeway with tax-paying uses, and better neighborhoods for new generations. Across the country, replaced urban freeways yield huge payoffs. Nationally freeway growth is slowing down, not speeding up. In fact, we have such results right here in Milwaukee with Park East.

For those unfamiliar, the Park East project removed a stretch of freeway and opened up new development opportunities. When first proposed, people worried that freeway removal would negatively impact commuting, worsen bottlenecks, and harm local business. Those concerns didn't materialize. Instead, over 20 years, Park East generated over $.5 billion in new public revenue, started new neighborhoods, attracted the Deer District, helped commuters, and created no traffic problems (despite 40,000 daily drivers). Developers, not taxpayers, paid for construction, and the community gained enormous property and sales tax revenue.

For 794, WisDOT’s “removal” option incudes at-grade street systems that keep traffic smooth. Commuters can arrive and leave comfortably. Downtown and the Third Ward can thrive. The bridge lift can get fixed. And over time delays will diminish. How can we do this?

First, remember freeways aren’t “free”. If the feds pay 90% of a rebuilt 794 freeway, the locals still pay millions but get no revenue in return. After “removal” however, if we fully use 20+ acres of open “opportunity” areas, then the private sector pays for buildings (including infrastructure), and the City reaps the reward. A $1 billion gain will come from property tax, sales tax, and decades of disposable income for jobs and economic growth. This requires using Milwaukee’s Downtown plan, partnering with other agencies and funding community-wide needs with new revenue.

Second, improve arterial routes for the 26,000 crosstown drivers on 794. Commuters have always needed improved arterials linking I-94/43 to their south shore communities. These arterial lifelines that connect suburbs to the freeway can be faster with improved driving times.

Third, use WisDOT’s “removal” plan to improve the street grid. The “removal” plan eliminates the mind-boggling confusion at the lakefront intersection – the huge stress point where the Hoan meets Lincoln Memorial. Redesigning this intersection makes driving much easier to/from downtown and the Third Ward.

Fourth, re-evaluate WisDOT’s data from broader perspectives outside a narrow project purview. We need to look at advances in commuter technologies and driver behavior, other transportation projects (like commuter rail), and how engineering interventions by other agencies can improve traffic redistribution on local streets and arterials.

Fifth, expand adaptive work patterns that reduce peak hour congestion. Traffic demand management can (a) help drivers use local streets easily, (b) shift some work hours to avoid traffic peaks, and (3) boost use of transit and biking. Even piecemeal actions will reduce delays and shorten commutes.

Sixth, balance fairer trade-offs. We should not split city and suburbs. Maximizing the system for one group at another’s expense does not work. We need a pragmatic system for pedestrians, bicyclists, commuters, tourists, rail passengers, transit users, etc.

Seventh, work patiently. Over 30 years, technology, cars and drivers will change and reach a new equilibrium. For example, new research has found counterintuitive outcomes that show how some freeway removals led to traffic count reduction without congestion. One explanation: new generations prefer cities to cars and like to avoid freeways.

These ideas can work and make “removal” the best WisDOT option. A transformational opportunity is knocking on our door in 2025. Let’s hope we do not regret our choice.