Reconnect Neighborhoods, Not Freeways — 175

Define The Right Mission — Urban Places

In 2021 the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) initiated the “Reconnecting Communities Program” to fix freeways in urban areas:

“the purpose of the [Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program] is to reconnect communities by removing, retrofitting, or mitigating transportation facilities like highways or rail lines that create barriers to community connectivity, including to mobility, access, or economic development. The program provides technical assistance and grant funding for planning and capital construction to address infrastructure barriers, reconnect communities, and improve peoples’ lives.”

The Planning Study In An Organizational Context

This federal program funded a study to look at feasible options to reconfigure part of the WIS 175 expressway. Specifically the study looks at an expressway segment over a two-mile long that borders a diverse set of neighborhoods, districts, and subareas. The places in the overall study area have been “disconnected” – pulled apart over decades by the freeway, railroad, topography and public policies. The reconnection plans for this area began by understanding the historic circumstances and acknowledging, from the outset, that there is no simple method for reconnection. Foremost in the planning process was an evaluation of the pattern of urban from surrounding WIS 175 and viewing the pattern of form through the lens of social and economic conditions which have impacted reconnection.

Most of the illustrations in this essay were first made public as part of the Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT) project entitled “Reimagine 175”. From 2023 through March 2025 the author worked on this project at GRAEF, Inc. GRAEF was the lead consultant for the large team of engineers, planners, and designers hired by WisDOT. During his tenure at GRAEF the author led the urban planning and urban design tasks for reconnection in parallel to to the transportation planning and the community engagement process. All of the opinions expressed in this essay are those of the author, not those of GRAEF or WisDOT. The illustrations shown in this essay are part of the public domain as of this writing (October 2025) unless specifically noted otherwise. Sources for the illustrations are noted using URLs available in 2025.

Although funded through WisDOT, both the City of Milwaukee and Milwaukee County were heavily involved in reviewing and commenting on the analysis and proposals throughout the process. From a planning perspective there were two separate sets of problems which required constant integration and reiteration — the transportation/traffic planning and the neighborhood reconnection planning. To succeed, both sets of problems must be resolved effectively. While transportation and traffic issues remain critical they are also subjects that have received decades of precise and careful engineering analysis, including issues of safety, speed, costs and benefits, regulation and jurisdiction, construction and operation. In comparison, neighborhood reconnection represents a relatively new professional focus for planners. The problems of neighborhood disconnection and reconnection have histories as long as transportation and traffic issues, The solutions, however, are only beginning to emerge and require far more attention to achieve clarity and success. Consequently, this essay, places the emphasis on the decision-making tasks for neighborhood reconnection surrounding WIS 175. Online sources from WisDOT provide ample description of the transportation and traffic issues

Planning Overview

The story surrounding this project is far from over. At this moment there are three alternatives which have moved forward for consideration. All three include both transportation/traffic recommendations as well as neighborhood reconnection proposals. It may take several years before a final integrated recommendation is developed and even longer for its implementation. This essay serves as a critical benchmark from a planning and urban design perspective. Future audiences may find this essay useful as a framework for evaluating the planning efforts in terms of what succeeds, what fails, and how planning and urban design fits into the larger history of Milwaukee.

The following three illustrations represent key moments, from 2023 to 2025, in the evolution of the plan for reconnecting neighborhoods.

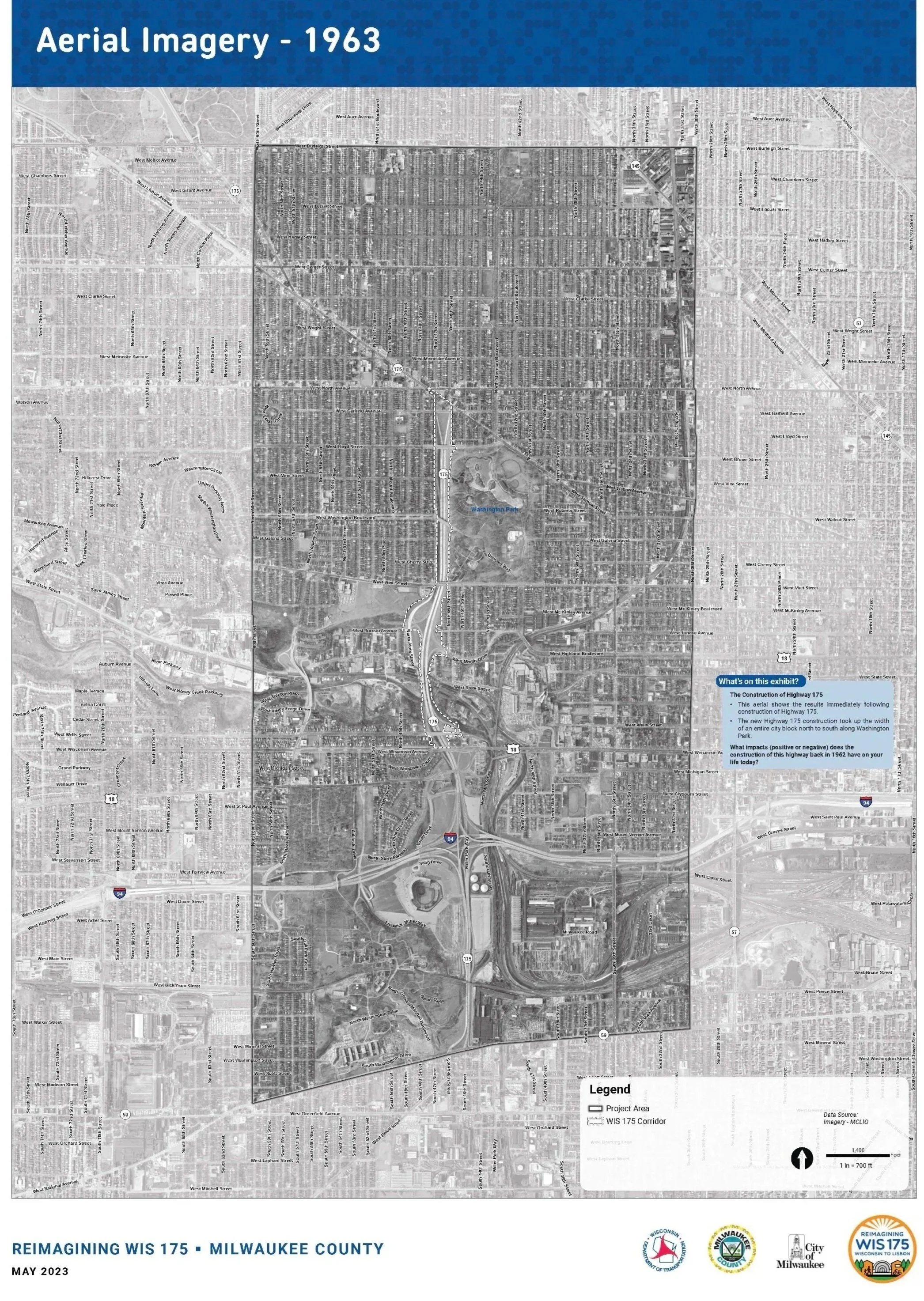

On the left, the 1963 aerial photograph shows the footprint of the expressway in a white dotted outline. Washington Park (by Olmsted) is clearly visible as is the freeway interchange to/from WIS 175 and I-94.

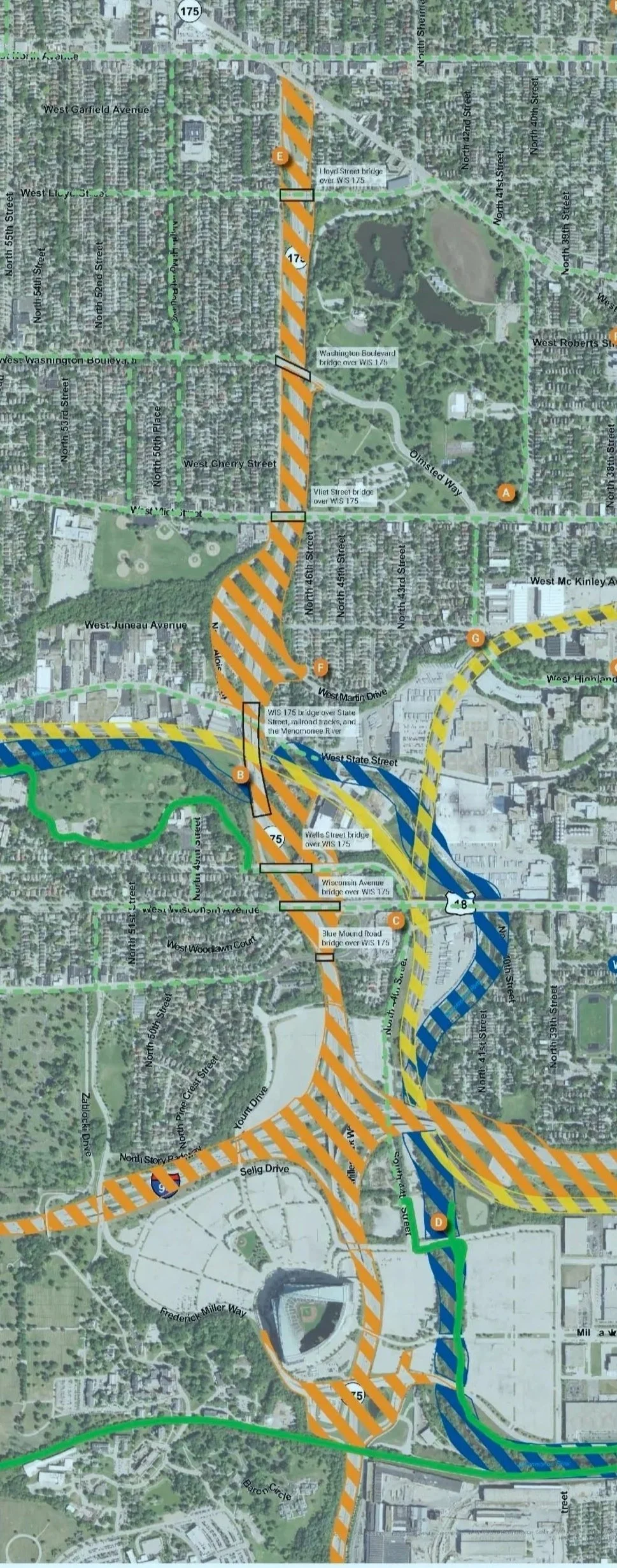

The center diagram points out the critical components of the urban form and pattern which figure prominently in all of the reconnection concepts.

The plan on the right represents one of the three proposal that is being carried forward for consideration and, in the author’s opinion, represents the best reconnection solution (it is referred to throughout this essay as a “preferred” solution.

The Story Begins With The Significance Of A Park

Volumes of data measure the social, economic, and political facts of the WIS 175 area. Not all data, however, bears relevance to strategies for reconnection. Most relevant data comes from viewing the issues of disconnection in a larger cultural context. Within that larger context, Washington Park stands our as a singular, complex, qualitative and highly relevant data point. WIS 175 borders the entire west edge of Washington Park. In addition, arterial links from WIS 175 extend along both the north and south edges. In sum, WIS 175 and its linkages surround the park and impact the park’s use and value. Conversations among planners, engineers, government agencies, and local community groups routinely emphasize the significance of Washington Park as the heart of the community.

The landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, envisioned a park that was central to the whole city (like Central Park in New York City, albeit much smaller). Olmsted believed that city residents from all backgrounds should have a place to come together in nature. His planned Washington Park was intended to appeal to a wide variety of people, economic classes, and population groups. The park is, a place to socialize, relax, and enjoy the rejuvenating powers of a natural setting.

Olmsted designed places to meet with friends and to be enjoyed across class boundaries. He emphasized lagoons in many of his parks as social centers for boating and ice skating. Today’s Urban Ecology Center may not duplicate his concepts exactly, but it clearly echoes his aspirations in a contemporary manner. The zoo and racetrack are gone but the park still draws visitors and fosters a sense of wonder in nature. The bandshell and music events have remained strong. Picnics may have diminished, but barbecues and tailgating have emerged. The playgrounds, ball fields and a hopefully renewed swimming facility are all consistent with his vision.

Many still see Washington Park as a “jewel in the crown” of Milwaukee’s. park system. Over time, during the twentieth century, some of the park’s vitality was lost. On the other hand, the park still has potential to restore its urban prominence, continue to integrate nature into the everyday life of the City, serve ongoing community needs and, importantly, catalyze opportunities for urban reconnection. Achieving such an objective relies, in part, on facilitating socialization and better engineering of circulation systems, especially for pedestrians. This is just one way in which neighborhood reconnection intertwines with better traffic engineering.

This set of illustrations presented to the public depicts many of the key components of Washington Park, including its rich history, activities, and ongoing operation. The maps were assembled by Wisconsin Department of Transportation. Online source:https://hdp-us-prod-app-graef-engage-files.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/7517/1450/2420/2024-04-30_WIS_175_PIM_2_Reconnection_Boards.pdf

After The Park, The Expressway Enabled Long-term Damage

While Washington Park became the social and cultural asset t,at fostered cohesive neighborhoods, the expressway and related infrastructure elements also became liabilities that engendered disconnections which could not be overcome easily. First barriers must be analyzed and examined in detail. Before the geography was urbanized, the rivers and topography where the only critical features in the landscape. Indigenous tribes and early settlers navigated such conditions regularly. Then, railroads emerged and transformed many of the linear patterns of circulation into stronger physical barriers. Railroads also created regulatory barriers by establishing rights-of-way. As commercial development grew abutting the railroad lines, so too did residential growth. Over decades many of the non-residential facilities fell into disrepair and were subject to disinvestment. Railroads, and their surrounding facilities, became dividing lines, disconnecting people on the “other side of the tracks”. Modest disconnections grew stronger and impacted real estate values.

When it became time to plan and build freeways the path of least resistance (and often the path of least land cost) followed the railroads, the river corridors, and the areas with lowered property values. Public policies in the form of zoning, land use regulations, and “redlining” also followed the same corridors, now built into in the urban fabric. While some forms of infrastructure have public appeal (such as older canals or reuse of rail lines for trails), such public appeal is not bestowed on most freeways. In sum, reconnection of neighborhoods must address simultaneously the collective visual, social, economic, and historic liabilities. The following diagram colorizes the lines of disconnections between urban places along the WIS 175 corridor.

This illustration diagrams the barriers of expressways, ramps, and railroads that divide and disconnect neighborhoods surrounding Wisconsin Highway 175. Over decades, in the author’s opinion, such disconnections produced social and economic harms that need to be repaired.

Source: Wisconsin Department of Transportation, Public Information Meeting #1.

Neighborhood Reconnection Builds On Local Character

Multiple neighborhoods surrounding Washington Park contain a wide range of strengths and weaknesses and offer major opportunities for improvements. Current housing options serve people at different stages of life and different socioeconomic backgrounds. Several housing pockets in these neighborhoods are culturally distinct with a unique look and feel worthy of preservation. A diverse housing stock helps drive economic resilience to the periodic shifts in the housing market. At the same time, the neighborhoods also show weaknesses in housing economics with lower household incomes, lower home ownership rates, and higher numbers of vacant properties. For reconnection, it will be important to maintain economic diversity, incrementally improve value, retain affordability, but avoid gentrification.

Housing structures in the study area include single-family homes, upper/lower duplexes, and multi-family buildings ranging from a few units to 20 or more units. Nearby multifamily developments successfully include even larger numbers of units. Local unit sizes also vary which further supports income diversity. However, east of Washington Park and north of Lloyd Street the vacancy rates, property value, and the home ownership rates, are much lower and need improvement. As might be expected these areas exhibit higher poverty rates and higher levels of racial segregation. In neighborhoods west and south of Washington Park the economic metrics are stronger, especially the Washington Heights neighborhood.

Over time reconnection can improve base on economic development , including job access as local transit systems are strengthened. Specifically the neighborhoods are reasonably close to major employment areas including: Downtown Milwaukee, Marquette University, Harley-Davidson, Molson Coors, the Milwaukee Regional Medical Center (MRMC), and the Veterans Administration Medical Center. Broader, more convenient transit will aid economic well-being.

This illustration shows demographic data surrounding the current alignment of WIS175. There is a noticeable demographic difference between neighborhoods east and west of the expressway. The expressway also amplifies the demographic differences surrounding Washington Park. The reconnection of these neighborhoods, and reduction in disparities, is a key goal of the 175 reconnection project. These maps come from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, Public Information Meeting #1 and reflect publicly available census and GIS data in 2025.

Reconnection Mitigates Chronic Inequities Embedded By Freeways

A long-term legacy of social and economic injustice overshadows the diverse milieu of people in the project area. While social and economic inequities may not be a first-order impact caused by freeways, the freeways do contribute to and reinforce secondary impacts which, over time, can be far more damaging and lead to permanent inequities. These inequities do not impact all residents at all times, but they add up over decades to create a legacy of negative long-term impacts. Some examples:

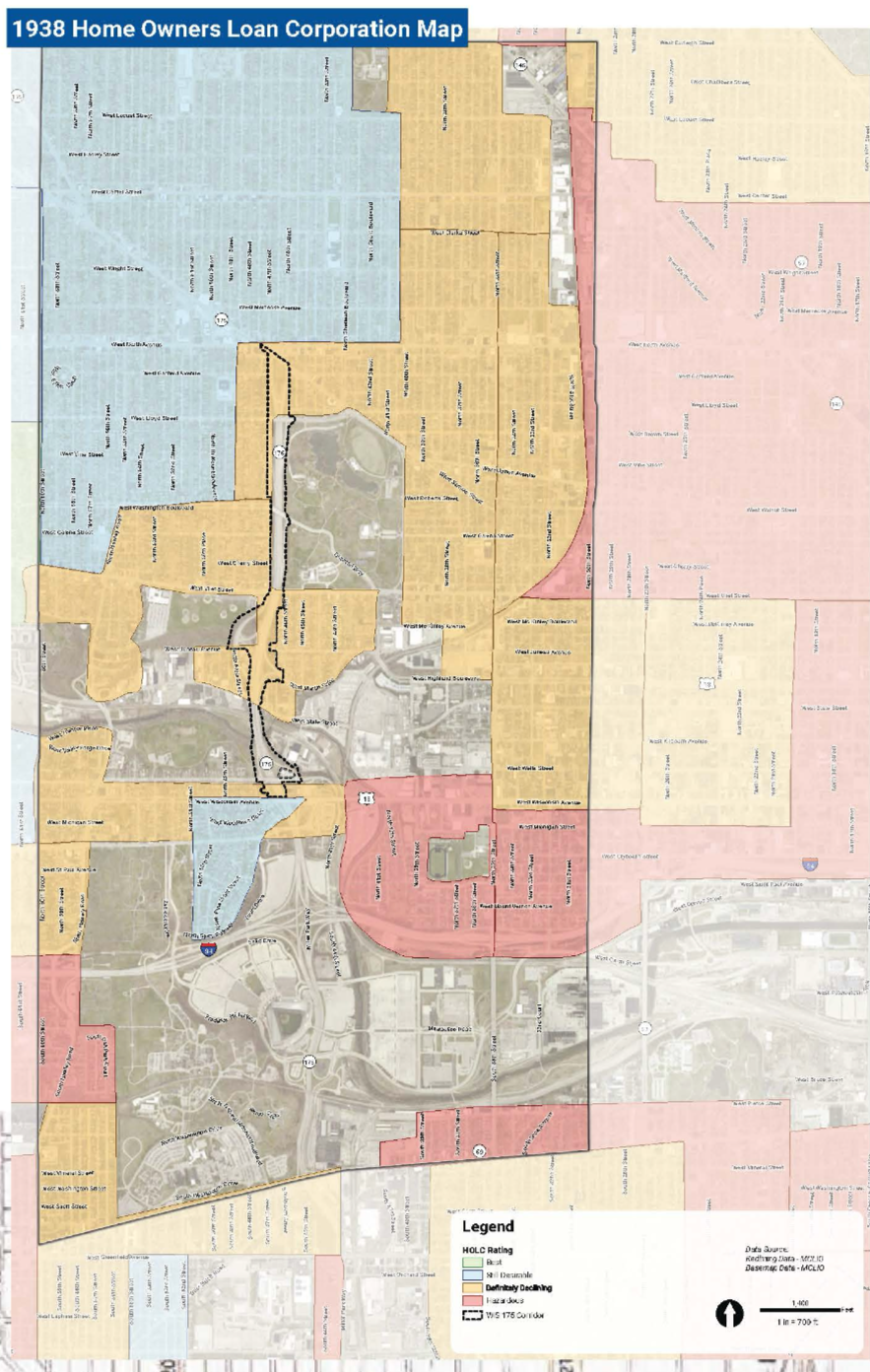

In the 1930s, the federal Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) mapped neighborhoods on a scale of investment risk. Areas labeled high risk were colored red. In became increasingly difficult to obtain mortgages at reasonable rates in these “red-lined” blocks. Over years initial inequity mushroomed into a chronic cycle of reduced ownership, lower resources for maintenance, physical deterioration and disinvestment. When combined with other social inequities it often became an overwhelming obstacle to families wanting to buy homes.

Energy burden is also an equity issue. As building insulation and home appliances age, they require more energy, especially when measured as a percentage of household income. Over time the scope of work needed for energy efficiency exceeds the resources of occupants and incentivizes absentee owners to avoid improvements.

People who live, work, or attend school near highly traffic-count roads also have an increased incidence and severity of health problems associated with air pollution (asthma, cardiovascular disease, impaired lungs, pre-term and low-birthweight infants, childhood leukemia, premature death). Again, this may not impact everyone on every day, but collectively, over time, these chronic conditions create clear inequities.

New development should not only avoid such inequities but also remediate the legacy that still exists.

This illustration shows the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) map from 1938 which was the beginning of urban “redlining” inequities. The portion of the map with darker tones represents the boundaries of the official WIS 175 study area. The areas of the map with the red tone (both inside and outside of the study boundary) represent areas where the HOLC loan policies clearly recommended against mortgage loans thereby setting a foundation for long-term neighborhood disinvestment in home ownership, repairs, and related private and public expenditures. Here too, the disconnection caused by the expressway increased the east-wet disconnection of neighborhoods.

This version of the HOLC map was reproduced from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, Public Information Meeting #1.

Leverage The Use Of Freeway Land With Long-Term Development Capacity

The weakened real estate market conditions in specific subareas of these neighborhoods is far from insurmountable. Many local conditions are susceptible to positive change over the long-term, especially if investors see game-changing improvements in Washington Park and the WIS 175 redevelopment area. Several other conditions also should be considered as positive features supporting local market capacity:

City Homes (17th and Walnut Streets) succeeded despite negative market expectations. The key to success was using local brokers to sell homes, subsidizing units, and creating strong visual appeal.

The Housing Authority of the City of Milwaukee (HACM) successfully implemented small scale projects (10-20 units) in multiple neighborhoods that work well and offer housing options priced for affordability.

HACM helped create the award-winning Westlawn neighborhood with strong visual appeal and a diversity of housing types across a large area.

The Community Development Alliance (CDA) established a program for affordable housing ownership that is feasible and should be used in this project.

The Park West area (noted previously) was surrounded by a weak market, but still produced critical improvements in surrounding areas, including the Fondy Market, Johnson Park, new industrial development and modest housing along Sherman Boulevard.

The Park East (east of Jefferson St. to Lake Michigan) filled in at a steady pace and today is fully reconnected linking neighborhoods from downtown up to Brady Street.

The MRMC created a major economic boom over the last 25 years in Wauwatosa. Some of this wealth has migrated eastward, along State Street, to less than a half of a mile from the study area.

National Avenue in Wests Allis, was envisioned as a comprehensive street corridor (development + complete streets) with multi-modal access for pedestrians, bikes, transit, and personal vehicles and offers a good example for the business development that can occur along WIS 175

The legacy of Washington Heights has a major appeal to developers.

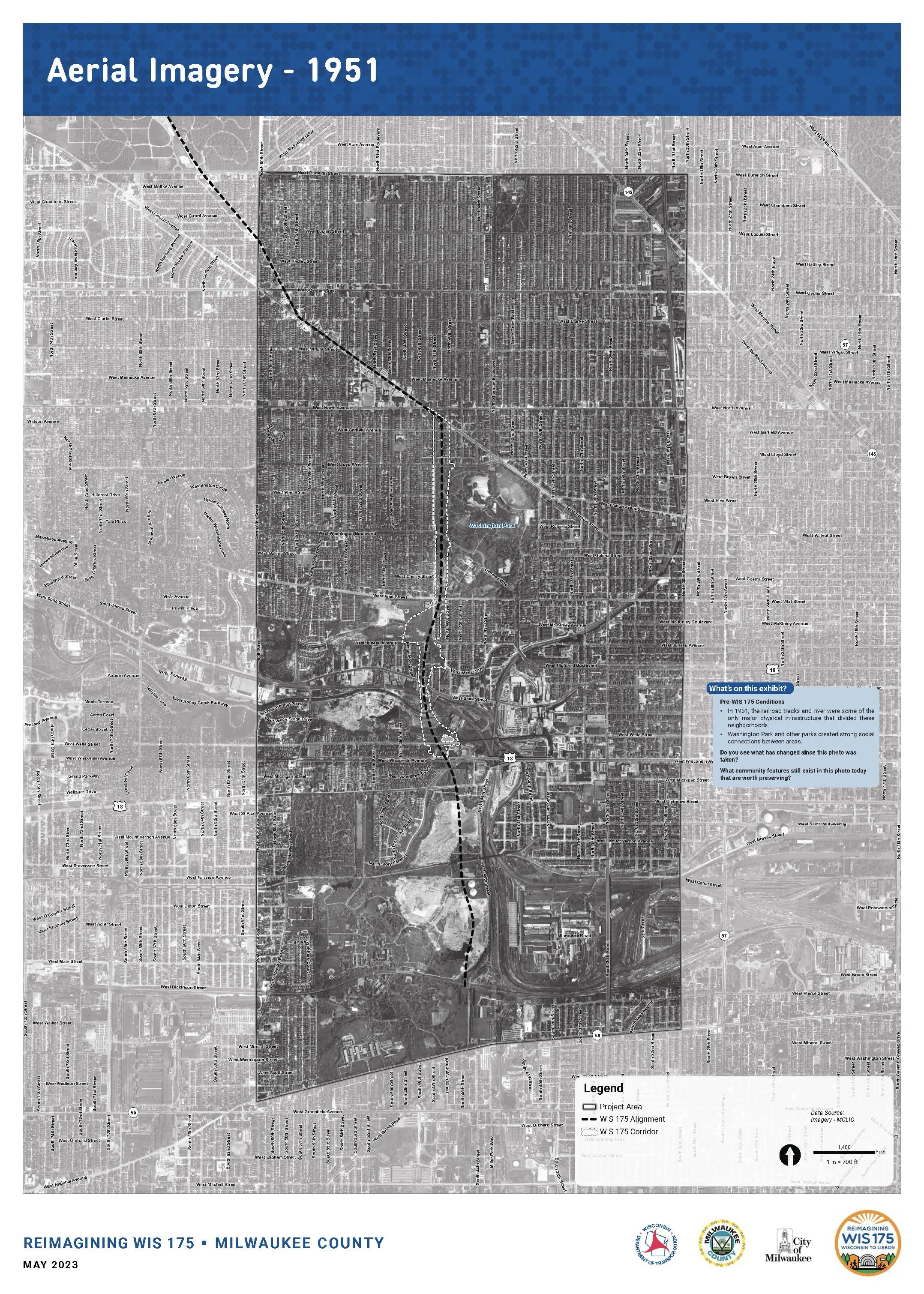

These illustrations show the clarity of the street and block grid that surrounded Washington Park and encouraged equal and continuous connection among the surrounding neighborhoods, especially for pedestrians and bicyclists. The map on the left shows the aerial view of the study area in 1951 before the freeway, with the future ROW alignment (in white) and the roadway centerline (in black). The map on the right from 1963 shows the freeway lanes in white and the ROW in white dashes. In addition the arterial streets (not emphasized) leading to/from the expressway contributed to the disconnection of neighborhoods. The maps come from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, Public Information Meeting #1. https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/mysocialpinpoint/uploads/redactor_assets/documents/04774e07f6393526dcc5cf700ada3529a8a94367866279c88e35ca1d116bfacf/78955/2023-05-11_WIS_175_PIM_1_Boards.pdf

Urban Design Can Help Remove Expressways

The physical foundation for “reconnection” rests on the integrated geometry of the streets, blocks, parcels, lots, built forms, architectural styles, landscape, and parking systems. This variable – urban design – combines with the social and economic conditions noted previously. All merge to create the urban “texture” or “fabric” that weaves neighborhoods together. These patterns, when analyzed and integrated, can create community reconnection. The analysis of the patterns of urban form surrounding WIS 175 is the first step in the urban design process intended to reconnect the surrounding neighborhoods.

The diagram on the left depicts the key patterns that form the neighborhoods surrounding WIS 175. The key patterns in the context of the site that must be respected by new solutions include the:

street, block, and lot pattern that defines most of the urban area and which has allowed for highly successful residential growth and activity

neighborhood commercial hubs as well as neighborhood activity hubs for a variety of social, economic, cultural and civic uses

major parks and gardens, including the prominent areas of Washington Park, Wick Field, and Doyne Park as well as smaller garden areas abutting homes and other smaller size land uses.

While this diagram was used throughout the urban design process as a reminder of the key elements of the urban form, it does not feature prominently in public presentations. This version of the diagram was created by the author (2025).

The area around WIS 175 evidences a high variation in market conditions. The market for new development shifts incrementally, sometimes with each block. It is essential to provide clear flexibility in the types of developments that can be created. The alternative discussed in this essay focus on residential development but include retail goods and services as well as cultural and non-profit activities. These alternatives assume growth will reach development capacity over time, using building forms and concepts consistent with both traditional neighborhood character and modest growth trend. As development unfolds, new TIF revenue will accumulate, some of which can aid affordable housing and risk reduction strategies.

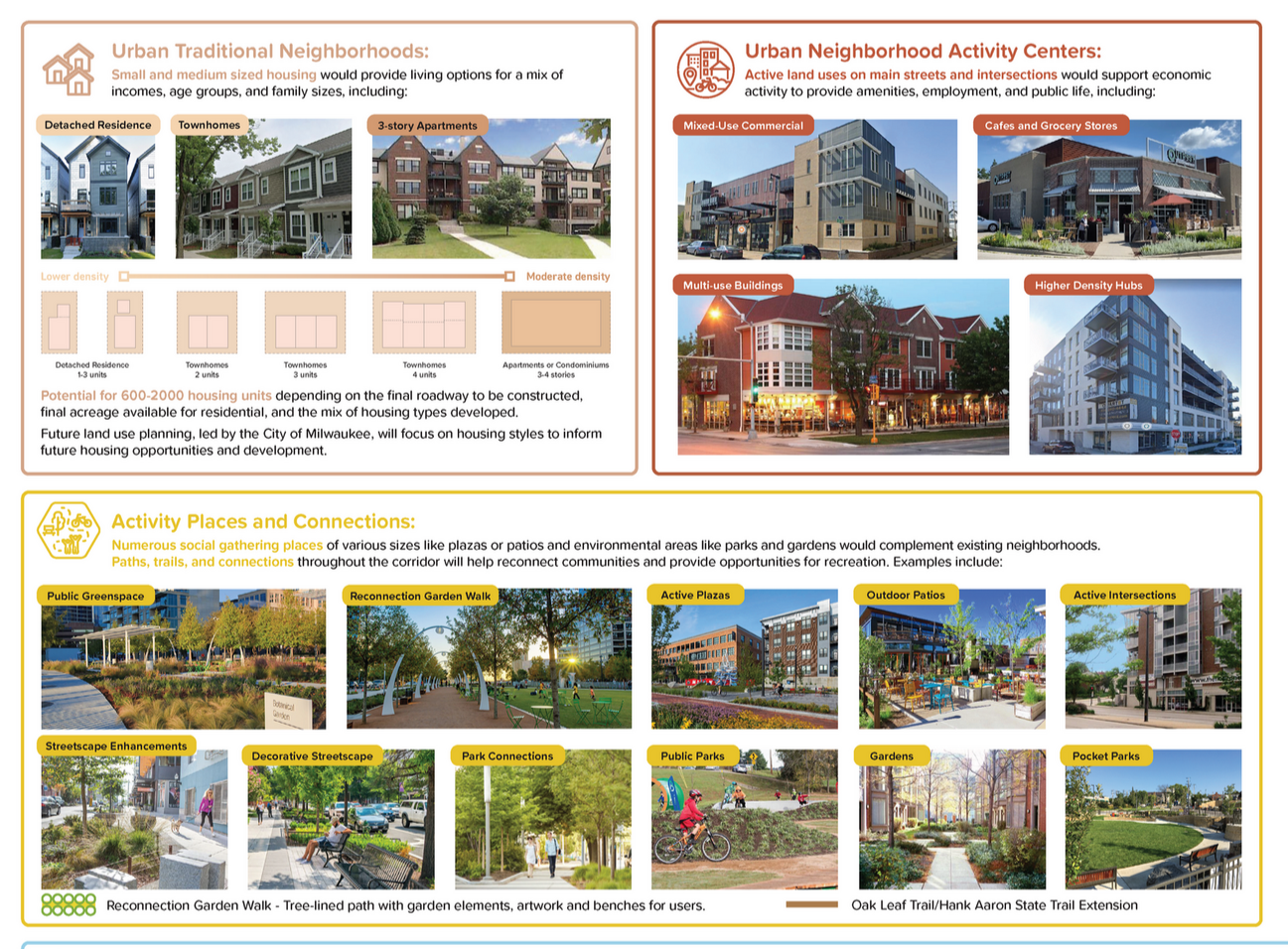

This set of illustrations above depict reconnection issues including traditional neighborhood housing patterns, potential for new business and commercial activity, new urban places, that can be used as local precedents.

Source for the illustration: https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/mysocialpinpoint/uploads/redactor_assets/documents/01e183bee7f5b4c5fc04cbe26c4a7bd1d92db34622fad8d02019d53b7610093f/96349/2025-04-02_WIS_175_PIM_3_Reconnection.pdf

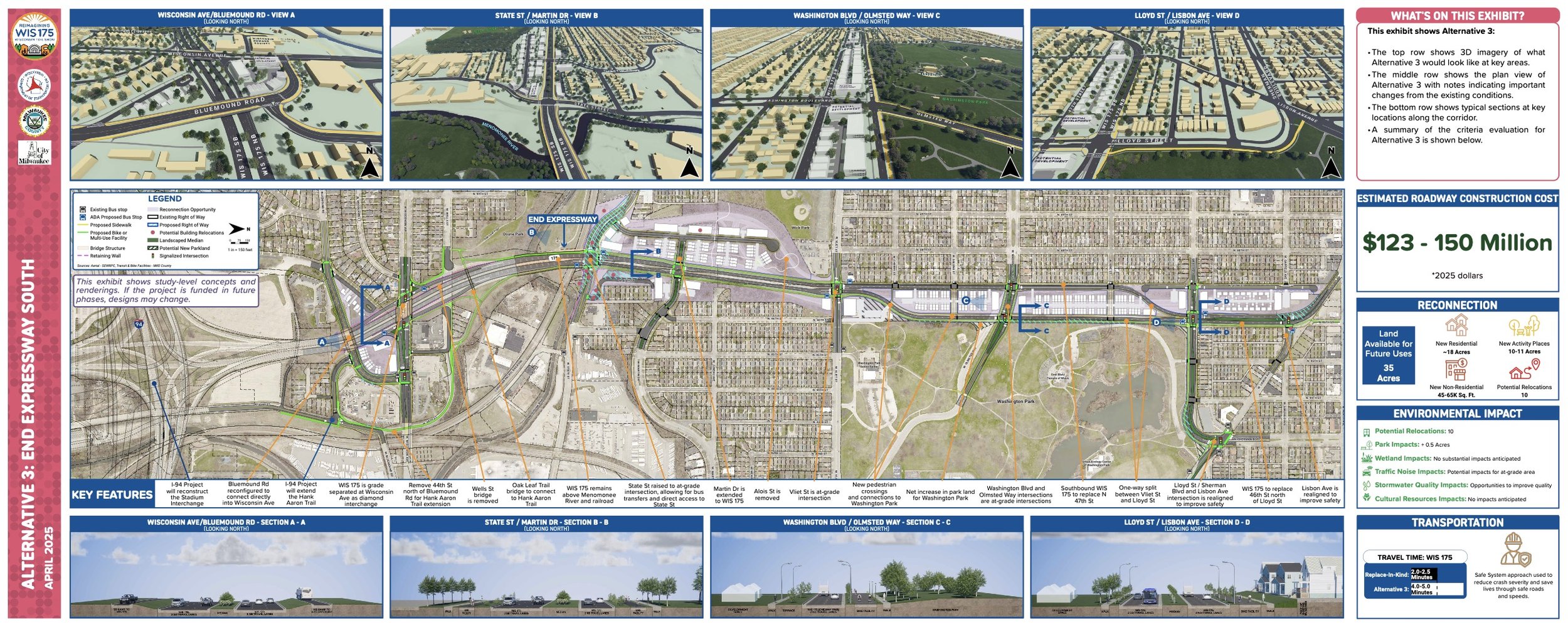

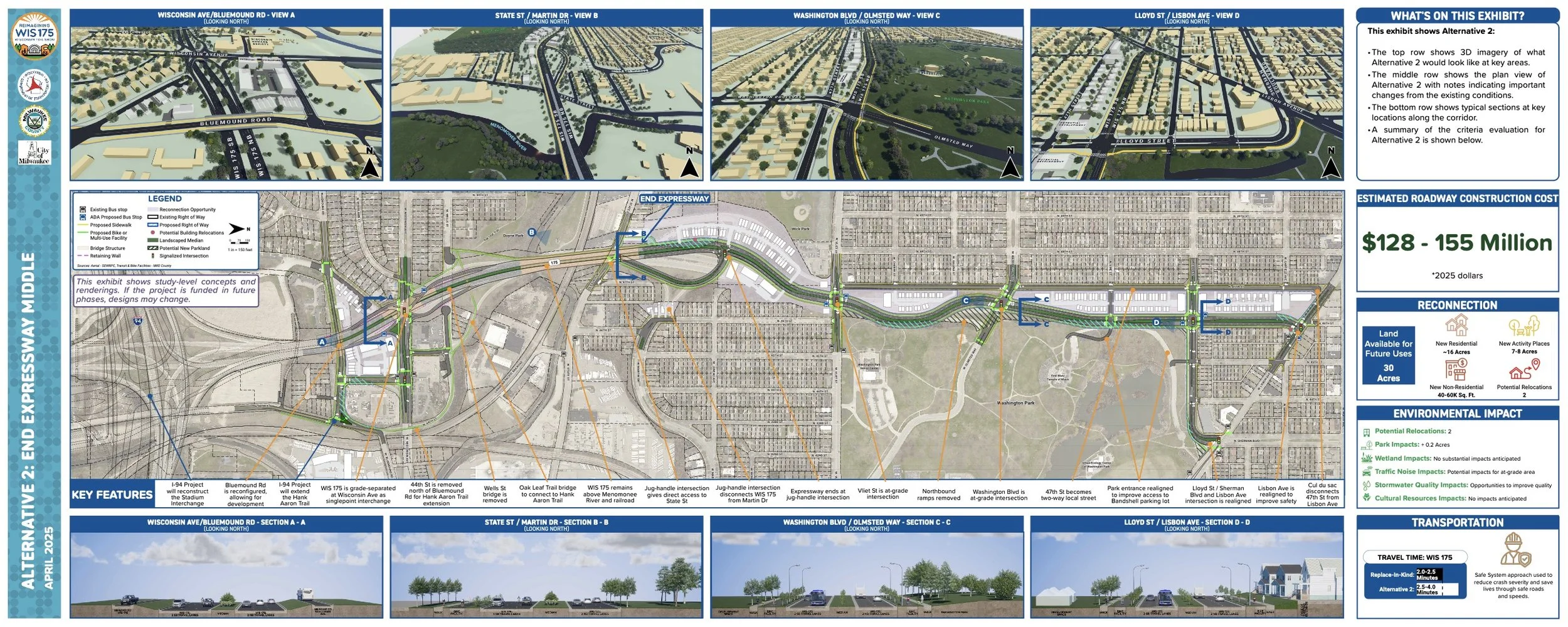

These three options were labeled according to transportation concepts as follows: (1) end the freeway at North Avenue, (2) end the freeway at the midpoint, and (3) end the freeway to the south. In the author’s opinion only option 3 (end the freeway south) address reconnection effectively and is referred to as the “preferred plan” because it provides sufficient opportunities to make neighborhood reconnection a likely, feasible outcome. The other options have merit, but are not likely to overcome the long term disconnections created by the expressway and related interventions.

Source for the illustration: https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/mysocialpinpoint/uploads/redactor_assets/documents/01e183bee7f5b4c5fc04cbe26c4a7bd1d92db34622fad8d02019d53b7610093f/96349/2025-04-02_WIS_175_PIM_3_Reconnection.pdf

Fix The City Form: Preferred Plan for Full Reconnection

In Alternative 3, the author’s preferred plan, the boulevard and an improved street grid begin near Wells and State Streets. This option reconnects the areas east and west of WIS 175 along the entire north/south corridor (from North Avenue to Bluemound Road). This alternative provides reconnection opportunities for the entire corridor and dramatically increases the probability of long-term reconnection. This option creates much higher densities along the edge of Washington Park, thereby increasing the potential for public revenue and reinvestment. The housing shown along 47th Street is smaller scale, intended to harmonize with the existing residential structures on the west side of the street.

There are many opportunities for different types of multifamily housing as well as duplexes. While the drawing includes many equally dimensioned footprints for buildings, as the development unfolds it is assumed that different financing and investment options will also lead to different architectural characteristics. At the same time, it is assumed that the fronts of all building will align along the street edges. By offering a comprehensive set of opportunities, this plan can succeed as part of an incremental development process — they more places that can be developed at each stage of the process, the more likely positive reconnection actions will occur. Solutions that offer more limited opportunities risk a higher likelihood of failure.

This plan can also be improved by adopting some of the individual components of other plans. For example, as shown in subsequent diagrams, the west side of the new boulevard south of Vliet Street can include better connections to/from Wick Park — that will make new housing more attractive and increase the potential socialization of the park by increasing access for more people. Also, as shown in Alternative 2, the buildings around Wisconsin Avenue and WIS 175 can increase density which will add value and offer more job opportunities along the BRT. Finally, at the hubs for commercial and community activity, the footprints shown in darker tone allow for multi-story mixed use buildings which, over time, can accommodate social and economic activities that will aid socialization and reconnection. Here too, by adding more opportunities there is a higher likelihood that a sufficient number will succeed.

Maximize Local Revenue For Investment

Most critical is the amount of public revenue that can be generated for investment in reconnection. The preferred alternative suggests that this total might be $250 million over 25 years (the next highest estimate is over 25% lower. Depending on the policies of public agencies, these funds can be used for affordable housing, home improvements, park facilities, a farmers market, streetscaping and other critical components needed for successful reconnection.

These data are approximations and reflect the work the author undertook while he was working at GRAEF, Inc. New data from GRAEF and/or WisDOT may change these estimates. Most critical is the amount of public revenue that can be generated for investment in reconnection. The table also shows metrics regarding building types, parking and other relevant metrics relevant to long-term implementation.

Fix City Form In Critical Places

As the urban design process continued it became clear that, in this specific urban context, there are five types of critical urban places which must be addressed in order to promote neighborhood reconnection. At the same time, any proposals addressing each type of urban place must also accommodate a transportation and traffic alternative that meets the needs and services as defined by WisDOT. This type of combined problem solving – transportation and urban design – has become increasingly important in the last decade as infrastructure problems get worse.

These maps illustrate the five types of urban places that form the basis for the design concepts critical to reconnecting neighborhoods surrounding WIS 175.

Type 1 - Washington Park Edges

Type 2 - Washington Park Interior

Type 3 - West Side of the Park

Type 4 - Crossroads and Main Streets

Type 5 - Underused Hillside & Land Areas

The illustration comes from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, and are located, as of 2025, online at :https://hdp-us-prod-app-graef-engage-files.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/7517/1450/2420/2024-04-30_WIS_175_PIM_2_Reconnection_Boards.pdf

Fixing Type 1 - The Washington Park Perimeter and Public Perception

Washington Park became the heart of this community before the freeway was planned, and still remains the living symbol of the area. If the Park goes downhill and loses its value, reconnection becomes impossible. The exterior appearance, along the park perimeter, determines the general public’s perception of the park and its context. If public perception improves, other improvements will gain political support. While perimeter improvement can be made in all options, it is assumed that this may not involve funding from WisDOT (with the possible exception of those traffic improvements that improve safety pedestrian continuity). Overall, there are three physical features needed to improve the perimeter:

The curb appeal on the private property across from the Park. Private property must be maintained and improved, including building facades and landscaping. This should only be proposed in concert with, and approval of the property owners. City policies should emphasize current grants and loans.

The public right-of-way must look orderly, well maintained, and safer with improved sidewalks, crosswalks, streetlights, furnishings, street parking, and signage. Pedestrian crossings at key intersections at the four corners of the park should be prioritized (especially with regard to pedestrian use by teenagers and younger children).

The landscaped edge of the park should be more attractive. with repaired walkways, trails, lighting and related features.

Throughout urban history, the perimeter of major parks and gardens becomes the place of great value. It is the perimeter of such urban places — the location of real estate — where built form, from individual residences to major civic buildings, achieves its highest value.

The illustrations come from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, and are located, as of 2025, online at :https://hdp-us-prod-app-graef-engage-files.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/7517/1450/2420/2024-04-30_WIS_175_PIM_2_Reconnection_Boards.pdf

Fixing Type 2 - The Washington Park Interior & Social Activation

The reconnection to all neighborhoods requires improvement to the park interior. Inside the Park, current activities must be sustained including music in the bandshell, the urban ecology center, senior center, playgrounds and athletic fields. The swimming pool must be reopened and improved. Other activities should be considered including a farmers’ market facility; and or a family-oriented food and beverage facility. It is worth emphasizing that a refurbished or new pool will also help restore confidence for both local and new investors. Along with the Urban Ecology Center, senior center and bandshell, this will dramatically increase the perceived value of the park and boost the appeal of the surrounding area.

The preferred design option allows for expansion and or relocation of the senior center along with a farmers’ market serving as a source of nutritious food, as well as a social meeting place. The preferred option also includes property development which, if managed effectively, can generate $250 million in revenue over 25 years. While some new park improvements can be funded through periodic government actions and philanthropy, there are always critical components that are not typically paid for from these sources and which can best be implemented by generating new revenue.

Like many parks in Milwaukee County, Washington Park has become a beloved local place. Every group that has commented on reconnection plans has supported the value of the park. The future of reconnection and the future of the park are one and the same.

The illustrations come from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, and are located, as of 2025, online at :https://hdp-us-prod-app-graef-engage-files.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/7517/1450/2420/2024-04-30_WIS_175_PIM_2_Reconnection_Boards.pdf

Fixing Type 3 - Revenue From The West Edge of Washington Park

The land west of Washington Park, within the current WIS 175 right-of-way, can be redeveloped to add community value, including both economic value in the form of new public revenue as well as social value in the form of new residents and activities. Effective urban design and development reinforces traditional neighborhood value, with:

Maximum access points at each block for pedestrian links east and west

Small-scale townhomes (facing neighborhood homes)

Moderate-scale apartment buildings with 3-5 stories (facing the park and businesses)

Safe and easy pedestrian street crossings for multiple populations

Garden areas, courts and plazas (with access)

This preferred urban design offers many more options for the design and diversity of residential units on the former expressway right-of-way. The design emphasizes appealing housing locations linked to views of the park as well as safe, comfortable and enjoyable access. The diversity of building opportunities allows for harmonious visual character and therefore greater harmony with Washington Heights. The fully public garden walk, a pedestrian promenade with a classic double row of trees, links housing, not only to the park but also to activities further south and into the valley. A direct, at grade connection on Lloyd, Vine, Washington Boulevard, Galena, Cherry, and Vliet Streets is also critical to the social and economic value of each block.

The built forms harmonize with the buildings and streets of the neighborhood. The preferred housing development includes both 2-3 story town homes facing neighborhood residences as well as 3-5 story apartment buildings facing the park and located along the north and south ends of each block. This pattern helps ensure market options for mixed income housing stock within each block and along each street edge. The few areas where the parcel geometry does not favor marketable buildings, can be used for small-scale semi-public places that are quiet, intimate gardens that, from a market perspective, are more likely to attract investors seeking higher economic value. In turn, such property value yields higher public revenue for the community. Other alternative plans may offer similar attributes but not at the same scale, quality and quantity thereby reducing the degree of successful reconnection.

A diversity of housing types and built forms includes 2-3-story townhomes and 3-5-story apartment buildings along the north and south ends of each block. This will facilitate mixed-income housing, avoid the appearance of a single “project”, and match the visual diversity in the neighborhood. The plan also includes small-scale semi-public places with quiet, intimate gardens that, from a market perspective, are more likely to attract higher value-seeking investors.

The illustrations come from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, and are located, as of 2025, online at :https://hdp-us-prod-app-graef-engage-files.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/7517/1450/2420/2024-04-30_WIS_175_PIM_2_Reconnection_Boards.pdf

Fixing Type 4 - Activating Underused Crossroads & Main Streets

Long-term social and economic reconnection requires revitalization of robust business activities along neighborhood main streets and hubs as shown in the urban pattern diagram. In these preferred design these activity hubs can be located at:

Lisbon Avenue

Lloyd Street

Vliet Street

State Street

Wisconsin Avenue and Bluemound Road

Multiple at-grade intersections in the preferred plan (at North Avenue, Lisbon Avenue, Lloyd Street and Vliet Street) all establish a sustainable market opportunity for nonresidential community-oriented investments. At first, during the early phases of redevelopment, these activities may focus on small businesses that are oriented towards the local population. If, however, they include new types of uses, they will create a strong sense of reconnection. The degree to which these intersections promote reconnection and increase the perceived market value will depend largely on (a) creating pedestrian connections that are safe, appealing, and encouraging and (b) convenient access for local parking and bicycle movement.

The major difference between the preferred option and other options is the major at-grade intersection at State Street. This is a powerful opportunity to boost the market value of the overall project. This design concept requires some relocations which can be mitigated but, in return, it creates an entirely new development opportunity. This option creates an economic gateway to the area by integrating the growing development potential east-west on State with the potential growth north-south on WIS 175.

Last, the hub along Wisconsin Avenue may be perceived as relatively removed from the neighborhood, but it can still increase in value in the long term assuming the BRT succeeds. The development pattern for this hub is largely self-contained but, if viewed in conjunction with the economic opportunity at State Street, this hub can increase the perceived value of the boulevard and this location. The hubs along Wisconsin Avenue (near the BRT) may also experience increases in value independent of the other areas.

The multiple neighborhood “hubs” should include different non-residential activities including small local retail outlets, professional services, community activities and institutional uses. Such activities typically follow an increase in residential density and local income.

The illustrations come from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, and are located, as of 2025, online at :https://hdp-us-prod-app-graef-engage-files.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/7517/1450/2420/2024-04-30_WIS_175_PIM_2_Reconnection_Boards.pdf

Fixing Type 5 - Leverage The Underused Hillside & Create A New Neighborhood

The dramatic topographic change from Vliet Street down the hillside to State Street defines a unique geographic area for community growth. This area should include urban places for multiple types of residential development as well as environmental preservation for reconnecting natural areas, including:

New housing with spectacular views of, and direct access to, natural amenities.

Environmental conservation and community access to trails and wooded areas.

Connections to Hawthorne Glenn to the west and environmental corridors within the Menomonee River Valley

The hillside, and the underutilized land, in the preferred design option includes a stronger, more cohesive high value for potential development. Housing units in this location will be perceived as a stronger independent enclave. Housing should include both smaller scale townhomes as well as larger apartments along the edge of the boulevard. The at-grade intersection at State Street is especially critical to the market value in this location and the overall project. New residential buildings can boost market opportunities for non-residential uses at this location. Housing in this area includes potentially attractive park space to the west (Wick Field) as well as current environmental areas. This enclave will be perceived as a natural neighborhood extension of development along the northern sections of WIS 175 to Lisbon Avenue. Collectively this will create a strong market perception, especially if the development is designed and planned with continuity.

Hillside housing, when designed sensitively by talented architects, can become a catalyst for community growth. The hillside in the preferred plan offers opportunities along with an at-grade community gateway and activity hub at State Street.

The illustrations come from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, and are located, as of 2025, online at :https://hdp-us-prod-app-graef-engage-files.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/7517/1450/2420/2024-04-30_WIS_175_PIM_2_Reconnection_Boards.pdf

Mitigate Inequities By Building Equitable Wealth

In any plans the risk for new private development needs to be mitigated with combined support from other public agencies. Achieving risk reduction is always a controversial subject but it is also necessary. The urban design concepts in these proposals offer a variety of ways to reduce market risk. At the same time, reduction of market risks should be paired with reductions in inequities. Agreements or policies can be proposed for effective affordable housing along with TIF financing and subsidies.

While WIS 175 replacement needs to resolve inequities, it is only one part of the answer. Other urban policies and programs – both public and private – must contribute to overcoming the historic economic and social inequities in the study area. Two of the most important conditions to overcome are the lack of home ownership opportunities and the lack of available financing for historically marginalized population groups in the study area.

Policies to remediate the negative socioeconomic outcomes of the last decades require neighborhood wealth building. Neighborhood wealth building rests on the principle of property ownership and emphasizes the importance of community-backed development. In this model, cities can also serve as proactive catalysts property managers and developers. Cities as corporate entities can own and develop land. As owners they can go much further than zoning:

Cities can decide specific types of housing, construction, property management, buy/sell agreements, deed restrictions, etc.

The City of Milwaukee can continue to build and rent units, lease land to other owners, or establish direct developer agreements with new owners that enable positive reconnection outcomes.

The City can draft developer agreements with the owner/seller.

The City can specify uses and policies in terms of parking, view corridors, building heights, rent structure, and sales structure.

Finally, if the City can demonstrate a program for neighborhood wealth building (or, in terms of this project, “neighborhood wealth reconnection”) then perhaps WisDOT might forgo payments for the transaction as compensation for decades of neighborhood wealth debilitation.

Analyze Equity In Urban Design

This tables below lists the criteria for equitable reconnection in this project and the actions needed in each of the 5 five types of places to reach the higher level criteria for reconnection. The valuations are based on empirical observations, metrics, and reports from community participants, agency staff and past work in the project area. Observations derive from the frequency, magnitude, and significance of proposed actions as they impact reconnection and associated inequities.

These three sets of criteria (physical, economic, social) represent the three crucial components of an equitable reconnection plan. In some ways the degree to which a plan satisfies these three criteria can be considered conceptually equivalent to the idea of a “level of service” used to measure the relative value of transportation plans. Based on these criteria, the preferred design option will rank the highest in terms of reconnection equity (also shown in the next table)

After defining the crucial criteria for evaluating a plan in terms of its “reconnection” value, those criteria need to be applied to each alternative plan and to each of the five types of places listed along the left side of this table. Unlike other aspects of transportation planning, reconnection planning involves more qualitative issues that must be judged as nominal or ordinal using the expertise of experts and/or others knowledgeable about the circumstance. This was the basis for evaluating the preferred alternative as superior to the others from the standpoint of equitable outcomes for reconnection.

Navigate The Road Forward To A Reconnection Destination

At this time, fall 2025, the planning process is ongoing. As in any complex project with broad goals (like “neighborhood reconnection” and “traffic improvement)”) many changes occur throughout the decision-making process. At the same time ideas from past options may resurface. Below are several design ideas regarding neighborhood reconnection that were set aside previously. These drawings are the personal files of the author developed during his tenure at GRAEF with support from other members of the planning and urban design team. These concepts have not been vetted by WisDOT, GRAEF, or the other consultants involved in the project but they do overlap parts of current WisDOT options. They were intended only to address issues of neighborhood reconnection and may be useful as a resource in the future.

This sketch shows a different design concept for the hillside, connecting the housing directly to Wick Park and providing a more robust circulation and street system. This option also shows a higher intensity Wiscosin Avenue hub that might develop in based on the relatively new Milwaukee BRT system. In addition, the thin brown line shows more pronounced trail system, for hiking and biking, that interconnects more parks and environmental areas. All of these concept can be incorporated into the preferred plan.

Throughout the process the author, and other members of the urban design team, develop hand sketches such as this one, to examine different street and block systems, building forms, and circulation systems. This behind-the-scenes work has more flexibiliity than computer-based sketching..

During the planning process one of the transportation options considered leaving the expressway at its current grade, approximately 30 feet below street level. If this were to occur, an intriguing design suggestion is the creation of a “sunken” garden below street level which, if designed in a detailed way, might become a city-wide attraction and, at the same time allow the expressway to retain some of its present alignments.

One of the early development concepts suggested the use of “enclaves” or courtyards of housing between the existing park and the residential neighborhood to the west. This would also include smaller gardens along the new WIS 175 and open up wider view corridors into the park from existing homes. In addition the meandering street alignment along park edge was more consistent with some of Olmsted’s picturesque carriageways.

This sketch explored the idea of roundabouts located to slow traffic and integrate with circulation inside the park. This design also tried to emphasize new gardens and larger public places between the park and the neighborhood.

The bright yellow line in this design represents a landscaped promenade that not only runs along the west side of the park but also continues north and south (even into the valley). This “garden walk promenade”, could become a signature feature symbolizing reconnection and implementing a form of appealing pedestrian feature while adding value to new development.

Conceivably, government policies might reduce or eliminate the goal of “reconnection”. Shifts in basic goals often reflect changes in political leadership or economic conditions. In some cases, like the Park West project for example, local government completely shelved the project in favor of other priorities. On the other hand, public policies might strengthen the project mission.

This case study assumes that the project mission will retain both transportation and reconnection missions. When both fields are combined, the problems and solutions become even more intricate over time. At this stage WisDOT has integrated all of the transportation and reconnection plans into three alternatives, all of which are moving forward for consideration. Only two of these three options are depicted in the following illustrations (the third Alternative 1, simply rebuilds most of the expressway).

The two options shown above require an extremely complex set of visual communication features (photographs, keys, notations, multiple line weights and colors, and lengthy, detailed text). Such complexity is needed to combine both transportation and reconnection details in one illustration. The top drawing (named by WisDOT as Alternative 3) follows the same concepts as the “preferred” option (but with lower densities facing the park). Alternative 2 also follows the option shown previously in this document but with less density. Not shown is Alternative 1 (which can be found online) that is far less consistent with effective neighborhood reconnection and equitable development. https://graef.mysocialpinpoint.com/wisdot175/wisdot-175-pim3/

Local community priorities always change and, in cases like reimagining Wis 175, plans may change significantly. Future plans may:

Exclude any new residential development (this might dramatically reduce the opportunities to generate public revenue for improvements)

Conduct the project in phases such that the changes in Washington Park are postponed indefinitely

Change the funding priorities for internal Washington Park Improvements

Transfer land ownership to other organizations (both for-profit and/or not-for-profit) who, in turn, might change neighborhood goals to other community issues.

Engage a private sector developer who might choose to build much taller buildings in one location and await market shifts before developing other areas parcel.

Engage a not-for-profit agency to build affordable housing units for large areas of land and avoid the complexity of multi-income housing.

Perhaps the most challenge will be adopting the preferred plan (or similar version) and implement the details effectively. This may require:

A regulatory framework (like form-based code or regulating plan) to ensure that all opportunities remain open for effective reconnection.

A shared funding agreement among the various levels of government

A not-for-profit agency that can manage a complex development scenario inclusive of both market-rate housing and affordable housing.

A redevelopment plan, adopted by the City, inclusive of options for community wealth building (such as a “land development trust” or equivalent group)

Past experience with freeway projects has taught us that implementation only occurs with continued perseverance on the part of the local community and leadership. All of the freeway projects noted in these essays unfolded over a longer time period, often with many ups and downs along the way. The future change of neighborhoods around WIS 175 is just starting. The implementation scenarios described here represent just a few possible directions. In practice every freeway project leads to some change incorporating some, but not all, of the proposed recommendations.

Notes

Wisconsin Department of Transportation held several large public meetings as well as numerous smaller public meetings with neighborhood groups, stakeholders, and others. In instances where graphics may not be part of the public domain, the source for the information is noted. When no source is listed, it is the work of the author. As of October 2025 the following online URL will direct readers to the WisDOT project website:

https://graef.mysocialpinpoint.com/wisdot175/wisdot-175-pim3/

https://wisconsindot.gov/Pages/projects/by-region/se/175study/default.aspx

If the addresses do not provide access readers should search for Reimagining WIS 175 Study