Milwaukee’s Incremental Freeway Changes & Park East

Understand How Freeway Barriers Get Worse

To begin an analysis of urban freeways and their impact on the city, we first have to understand how freeways become embedded barriers which, in turn, have negative consequences. Some embedded urban barriers fit the essential form of the city like rivers, lakes, and major topographic changes. Over centuries planners found ways to transform natural barriers into assets that add value like desirable views, access to shorelines, and related features. Ancient aqueducts and canal systems add a sense of romance to a pastoral view, but transmission lines, pipelines, and similar structures have not yet become appealing. When these barriers are removed new growth occurs — like the Park East area in Milwaukee.

In many cities, potentially negative barriers go underground like subways, steam tunnels, sewer and water systems, and even some freeways. The large added cost of hiding infrastructure implies that, for many cities, the cost of avoiding harmful visual barriers deserves large expenditure. Boston’s Big Dig is a spectacular example of how the harm caused by freeway barriers was presumably cured by placing the freeway below ground (at great cost to all levels of government). In most cities, however, planners face infrastructure barriers that create few redeeming opportunities.

Before Milwaukee Freeways: Railroads & Canals

The first signs of barriers in most cities appear with when railroad systems arrive. Many cities understood the problematic nature railroads and promptly built expensive tunnels or elevated tracks. Even those elevated tracks became problematic but, unlike freeways, the elevated rail systems allow for fully functioning at-grade streets and even some spectacular transformations like New York City’s High Line. More often, in response to new railroads, new industrial and commercial structures were built adjacent to the tracks. While freeways demand major interchanges, railroads use sidings and railyards that spawn large facilities. Homes built near railroad-based industries were well positioned for employees to walk to work.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in the Georgetown r of Washington D.C., provides an exemplary model of how an industrial, commercial facility can become and aesthetic and functional gem amidst a dense urban environment. While there have been many efforts to add cosmetic changes to freeway structures, major success still elude designers and observers.

Over time, visual and functional uses near railroads languished. Disinvestment became normal. Upgrades stopped. Other transportation systems (like freeways) gained value as a more efficient alternative. Today, century-old railroad conditions remain as part of the challenge to reconnect the communities. While “rails to trails” have given the older railroad rights-of-way new life, many railroad systems still debilitate urban areas. Mitigation of railroad barriers (especially urban railyards) occurs in many cities but rarely erases the decades-long legacy of negative urban impacts.

This figure-ground map (buildings are shown in black and all else is left white) portrays the essential urban pattern of Milwaukee in 1950. At this point it time, the street and block system is strong and supportive of urban life, only to be drastically injured by the upcoming freeways and renewal projects. While this precise historical street and block pattern cannot be reconstructed, the underlying principles can be used to repair the damage caused by freeway barriers, especially with regard to visual character, circulation, and social and economic activity.

Some of the early railroad barriers have transformed from liabilities to assets. While not as prominent as the High Line, Milwaukee has several rails-to-trail projects demonstrating transformations of older rail systems into new assets (such as the Oak Leaf Trail and Hank Aaron trail). Milwaukee and other communities know that there must be a balance between the efficiency of urban, suburban and rural transportation systems.

Before the railroads, canal systems emerged echoing canal networks in European regions. Unlike railroads or freeways, when canals lose their industrial and commercial value, they retain their visual and cultural value. Adjacencies to canal can provide some of the highest and best real estate. The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal (shown above) clearly adds value to Georgetown. Freeways, however, have yet to be perceived as inspiring aesthetic cultural objects, a condition that still confounds effective urban planning.

Freeways Split Neighborhoods

Freeways came with much wider and invasive structures than railroads (as well as larger land areas for ramps and the needed arterial networks for traffic distribution). More importantly freeways also dominated the street level. Early elevated freeways allowed the local street system to continue at grade. While this technique appeared at first to allow at-grade continuity of urban activity, eventually the logistics of maintaining and operating above grade structures exacerbated freeway barriers and help generate dead or dormant street level conditions.

Areas around interchanges soon developed large auto-oriented structures with surface lots. Such development did not fit cities but became praiseworthy as it echoed newer suburbs. Over time, the edges of freeway barriers expanded and became either dormant or less attractive or both. Urban connectivity became more difficult, and loss of value rippled into surrounding neighborhoods. As freeways and railroads, grew separated neighborhoods became more isolated.

Some separated neighborhoods grew stronger internally, built upon their inherent pattern of harmonious buildings organized on simple streets and blocks with small parcels. Other neighborhoods with similar structure (perhaps on the “wrong side of the tracks”) grew weaker. In recent years, the anti-urban isolation of neighborhoods has yielded issues of gentrification, segregation, and partisanship. Planners have yet to find ways to mitigate barriers and return to the once-healthy patterns of integrated growth and revitalization.

Fix Freeways By Prioritizing Neighborhoods And Networks

Developing neighborhoods requires the highest talents and skills, enormous levels of coordination, and major resources for financing, operations and innovation. If we think freeways are complex, good neighborhoods are even more nuanced. You cannot “keep it simple”. Neighborhoods are hard to measure. There is no standard “level of service”. Values are highly subjective and vary within and among cities and regions. Persons less familiar with freeways and neighborhoods, including professional designers in all fields, often fail (or refuse) to grasp the enormity of such challenges. Now the challenge of integrating solutions to both sets of issues (neighborhoods and transportation) has become an even more “wicked” problem.

Decades of trial and error, success and failure, must be understood in order to co-develop major highways and neighborhoods. We cannot do one without the other. If we characterize the essence of freeways as “systems” and the essence of neighborhoods as “places” we may have a chance. At least, that seems to be the accumulated lesson from decades of such projects in Milwaukee.

Among our multi-layered governments we face chronic turbulence. Seeking at least partial rationality in this milieu seems Quixotic. Perhaps we are “tilting” at freeways, failing to see them as what they are, as well as what they could be. The decision-making quandaries regarding freeways and neighborhood places will not diminish. So, what can practice planners do?

Mediate City/Suburb Freeway Conflicts

Freeways must help, or at least not harm, urban, suburban and rural areas. This requires balanced planning for each type of community. Freeways still create a great value by providing fast access across long distances. Such traffic movement requires roadways with “limited access” that allow vehicles to move faster and safer. This still is an incredibly valuable service. Intercity and commuter train systems, for example, have been constantly improving. So too have freeway system, but not always in a way that helps the neighborhoods they traverse. Any resolution requires viewing such systems and places in their full social, economic, and physical context.

Resolve Negative Impacts Of Urban Freeways On Local Neighborhoods

Urban neighborhoods do not require faster traffic and access, but better safer, comfortable access for more people to engage in more diverse activities. Higher density places, thrive on multiple modes of access to multiple places as opposed to freeways that thrive on singular access to separated interchanges. They both have their place.

Urban freeways reconfigure effective non-hierarchical patterns of access needed in neighborhoods into stricter, less flexible hierarchical patterns needed for regions. The freeway-based hierarchical model of traffic, ultimately trickles down too far into cities, concretizing segregated land uses (aided by zoning) and reinforced by a legacy of property valuations. It has taken decades for planners to help reassert mixed use, multi-income neighborhoods, diverse social and cultural activities, and all of the other attributes that help urban neighborhoods thrive.

Freeways in suburban and rural areas exhibit the opposite traits. They provide the primary means of interconnecting distant areas and subareas to facilitate daily life. Suburban areas with segregated land uses, restrictive access, and less diversity are anathema in cities, but quite desirable in suburban districts. So why must we make suburbs be like cities or cities like suburbs? How can we accommodate both? How can they coexist? Too often our communities feel threatened by exaggerated warnings of change, xenophobia, and a loss of control. In the case of freeway changes, planners need to acknowledge such anxieties, address them fairly and directly. Planners should emphasize clear examples of likely outcomes as opposed to alarmist doom and gloom scenarios. Many suburbs, in the long run, are much better off if their nearby urban centers have higher value, more jobs, more interesting and desirable activities, and more revenue to support themselves.

Replace Urban Freeways With Good Boulevards

Freeways of course maximize one single variable – how fast you can drive safely from Point A to Point B. Other factors seem secondary including the cost of the vehicle and the fuel, aesthetics of the experience, impacts on the natural environment, and – especially important for urban areas – the social, economic, and political value of activity abutting the freeway. The edges of urban freeways also reinforce the discordance with neighborhoods. Freeway edges become impregnable, less appealing, and more value-reducing barriers with their legitimate need for separated lanes, fences, guardrails, shoulders, and sound walls. The same freeway that does not help property owners in urban places will help the values in suburbs and rural areas where freeways make sense. In short, the key to mitigation becomes the transitions from city to suburb or, in these case studies, the transition from freeway to boulevard.

When drivers reach the city and exit an urban freeway, they travel on a local arterial – a type of mini-freeway designed for fast traffic and vehicular movement. Effective arterials (with grassy medians and turn lanes) facilitate traffic but they should not be mistaken for urban boulevards. Most arterials lack the higher quality landscape, attractive facades, walkable features, slower speed and increased cross access that is essential to great boulevards. It may be hard to define the detailed different between a traffic oriented arterial and an urban boulevard, but most people know it when they see it.

Good boulevards offer maximum access to surrounding areas. They are designed for high-quality aesthetic impact, slow speeds to ensure pedestrian comfort and safety, as well as integrated use of other vehicles like scooters and bicycles. In some ways boulevards are the direct opposite of freeways. Boulevards add neighborhood value with activated wide sidewalks, heavily tree-lined edges and harmonious (but not identical) building facades.

Boulevards are clearly the roadway of choice for major traffic movements in urban areas while freeways (and their arterials) are clearly the roadway of choice for major traffic movements in suburbs and rural communities – neither one mode nor the other is better, but they must be used in their appropriate setting. Freeways in cities are harmful just as boulevards on rural areas would be wasteful.

Balance the Combined Value Of City And Suburb

The ability to integrate both freeways and boulevards does not require a whole new skill set or volumes of analysis. It does, however, require merging urban and suburban mindsets which, if left unbalanced and disconnected, produce dysfunctional outcomes. This merger of dichotomous belief systems only occurs if planners emphasize long term costs and benefits that can create win-win scenarios.

Over time, improving the value of denser urban areas improves the value of surrounding suburbs. The central business district of each major city is, in practice, the economic and cultural heart of the metropolitan region. The more the central city “heart” thrives, the more the suburbs thrive. When central city areas become less valuable and less attractive, the primary option for growth quickly moves to the suburbs, adding more subdivisions, adding more traffic and exponentially higher infrastructure costs (especially on a per capita basis). Suburbs want short term property value but not long-term infrastructure costs that usually lurk a decade or two ahead of annual budgets. Many post-war suburbs that began in the second half of the 20th century, already have fallen prey to this predicament. Suburbs today, just like city centers, need to rethink their long-term futures.

Look Back At History To Move Freeways Forward

Sometimes hindsight shows us a way to move forward. Haussmann’s Paris provides, perhaps, one of the best benchmark for comprehensive streets. His boulevards have everything from the right technical engineering, enormous social and economic value, and new facades that make truly complete and beautiful streets. When Olmsted created Haussmann-like boulevards in the United States, he fashioned well-functioning boulevards (before cars) that still operate today at high levels of value as well as transportation efficiency (such as Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway, Ocean Parkway and others). If these urban boulevards have worked for almost two centuries, then why cannot they work now? Why are good urban boulevards not replicated more often? Perhaps, we fail to recognize our older boulevards as good solutions because they lack speed, because they prioritize transit, because they are not suburb-oriented, because they do not follow the most recent “best practice” guidelines for arterials, or because they just seem old-fashioned at a time when anything more recent must be better.

These images of historic illustrations of Milwaukee, like many puzzles, offer solutions may seem hidden at first but which we can use today. From left to right: a street and block grid that encourages overlapping neighborhoods and integrates social and economic activity; a lakeshore bluff filled with circulation elements that celebrate the change in topography and the view of the lake; a street level promenade that includes multiple public investments recognizing our history; and design concepts that thrust public places outward from our neighborhoods and fully engage Lake Michigan.

Learn From Interrupted Freeways

This case study does not focus on why ‘freeway’ advocacy triumphed politically – urban planners often have little authority to counteract such decisions. But if, and when, urban freeways enter a remission phase, planning questions become paramount. How does freeway remission actually work at grade? What issues should be addressed? What are the variations in context and conditions? How should freeway transformation be implemented?

A series of projects is discussed below, each of which was intended to mitigate negative impacts in and around Milwaukee. Each of these projects faced varied conditions in which a freeway (or expressway) has been replaced or reconfigured. In these planning efforts, it is not the freeway changes that are ill-defined, but the surrounding urban conditions that account for the problem complexity. These problem complexities usually exhibit a much broader array of social and economic issues when compared to changes surrounding suburban and rural freeway. Each of the projects discussed here required wide-ranging talent and resources from planners representing different disciplines, skill sets, public missions and levels of government. Also, the project time frames overlap but they are presented here roughly in the order in which they were initialized.

Recognizing Neighborhood Preservation - Locust Street & The Growth Of Riverwest (1972-1978)

In 1973, there were transportation plans to widen Locust Street, east of the I-43 freeway interchange, across the Milwaukee River, and through the wealthier university-based eastside neighborhood all the way to the lakefront. Once it reached the lakefront, the arterial might connect to a wider arterial along the lakefront reaching south past the downtown to the I-794 freeway. The planned Locust Street arterial had already led to the demolition of several blocks of street frontage from 8th Street to Holton Avenue.

To complete this arterial system, newly demolished street frontage would harm, as might be expected, the largely black neighborhood abutting Locust Street. No redevelopment plans for the demolished area were put forward. Until this time, the cleared land remained vacant and unsightly. East of Holton, Locust Street was still intact and offered a minimally successful neighborhood main street for the area (soon to be renamed as “Riverwest”). Potential destruction of this neighborhood spine in favor of a so-called system-wide transportation arterial unleashed an intense political battle. The local neighborhood group, ESHAC, was pitted against the City’s leadership over the future of the area. As a university-based planner working for ESHAC we were tasked in demonstrating the potential value of the neighborhood both south and north of Locust street (each side of the neighborhood spine) and the need to treat the neighborhood as an integrated area with strong value. Two planning studies were produced: “Futures for Locust Street” (1973) and “The Redevelopment of Riverwest” (1978). It took a few years, but eventually the City leadership relented, relabeled the area as a “special” neighborhood and allowed it to chart its destiny in a more independent, but integrated manner. Over the years Riverwest grew in value as one diverse neighborhood. Locust Street and Riverwest represent a clear success story in preventing a freeway arterial from extending its damaging influence. Most recently new development on Locust, west of Holton has begun more than 50 years after the initial arterial demolition.

These hand-drawn images were critical to the “Redevelopment of Riverwest” because they gave the study a strong humanistic, albeit subjective, social, cultural, power. These places are still intact. Riverwest thrives. It would have been a neighborhood-wide casualty if the arterial was not stopped. Put another way, while freeway and arterial barriers harm neighborhoods, the absence of such barriers can help neighborhoods thrive.

Was there a unique planning issue underlying the strategy for saving Locust Street? In hindsight it seems the simple, critical issues was urban neighborhood preservation focused. This was not historic or architectural preservation – it was simply the social and economic preservation of Locust street as the unifying seam in a pedestrian friendly neighborhood. Not only has the neighborhood prospered, but Locust Street, and now Humboldt and Holton are also seeing signs of revitalization which can be expected to continue. Without the preservation of Locust Street activity, the story would not have ended successfully.

The “Redevelopment of Riverwest” is a modest planning document that had enormous influence because it gave social, physical, and economic legitimacy to the idea of preserving neighborhoods as an essential priority for urban planners. In the City, many other neighborhood plans were created following this landmark study. The above diagrams in the study emphasized critical issues regarding home ownership, income, existing urban places, catalytic projects and related issues. The document was created before planners had routine access to digital software, photographs, GIS, and related resources which today are commonplace. That is, the tools we use to communicate are secondary to establishing strong concepts.

Overcoming Disbelief - Park West Freeway 1974-1980

The Locust Street arterial dilemma did not involve new development. The potential for new growth to replace cleared land first occurred as part of efforts of the Park West Redevelopment Task Force. When the freeway system expansion was abandoned in this area, several miles of cleared land became dormant and left vacant. The demolition process had occurred in increments but left an obvious swath of cleared land from the north south freeway (I-43) westward to Sherman Boulevard — on this side of the north-south freeway the project was named “Park West”.

These images tell much of the story. The top row (from left to right) shows (1) portions of the cleared land (some of it is still undeveloped today in 2025); (2) the activity in the Fondy Market which was conceptualized by the Park West Redevelopment Task Force and given prominence engagement methods such as (3) a large scale physical model. The second row shows pictures of surrounding residential development which, to this day, has remained included high-quality housing. The bottom row shows some of the public engagement methods including (from left to right): (1) and illustration of new housing with a broad pedestrian promenade, (2) a local Task Force meeting with the project staff and neighborhood leaders and (3) a large scale model used to discuss and revise design options.

The Park West land became the subject of a major neighborhood revitalization effort under the direction a consortium of local groups called the Park West Redevelopment Task Force. This Task Force undertook initiatives that were successful as well as some that were thwarted by the City. Today unused and underused land remains, but several key investments have occurred. Some of the positive outcomes included:

Forging coordination and cooperation among several disparate community groups that helped support better local services and policies.

Creating a new County Park (Johnson Park) which remains a key community feature

Preparing the conceptual design and program for the Fondy Market which initially stalled due to a lack of City support but ultimately became a thriving community asset.

Obtaining $2 million from the US Economic Development Administration to start new business.

Supporting the expansion of Washington High School on its existing land rather than demolishing additional neighborhood housing.

Stopping the demolition and widening of Fond du Lac Avenue as a proposed high-speed arterial to link to I-41 and reinvesting in Fond du Lac Avenue as a key urban street.

The greatest difficulty was simply overcoming the disbelief of the general public that redevelopment of the area was feasible and that the homes that had been demolished could be replaced. Specifically it was difficult to revitalize the housing market without strong governmental support economically and politically. Many of the investment successes noted above occurred because of public actions from the County, State, or Federal government – while City support was missing for a variety of political reasons. The best way to view these efforts from a planning perspective is to credit the Task Force for stopping the negative impacts of the planned freeway, creating several positive neighborhood changes, and setting the stage for future groups to improve the area. In some ways the work of the Park West Development Task Force was “proof of concept” that urban planning focused on freeway land could have a strong urban value which, in turn, helped legitimize other freeway and arterial reconstruction efforts.

Emphasizing Opportunities – O’Donnell Park & The Downtown Lakefront

A primary hope for the planned freeway system was the continuation of the freeway from the north end of the Hoan Bridge along the downtown lakefront, turning west a few blocks north of the War Memorial. This freeway continuation would have created an enormous barrier separating the lakefront and the shoreline from the city. Access from the downtown bluff overlooking Lake Michigan had never been considered significant – such access was not cause for concern since it did not exist. Fortunately, the negative absence of a strong lakefront connection (visual and physical) was so overwhelming obvious, that all audiences knew that continuation of freeway construction would become the ultimate barrier killing connection from downtown to the lakefront.

The illustrations (left to right, top to bottom) include: (1) photograph of the 1970s lakefront devoid of any significant use with surface parking and the two freeway “stub ends” that remained when the freeway was stopped (2, 3, 4, and 5) the key urban design proposal called “Lake Terrace” that received strong community support and won a national award and (6) the facility implemented by Milwaukee County, albeit with a changed design. The lakefront area once slated for a freeway barrier became a set of lakefront jewels and symbol of Milwaukee.

In the late 1970s the City, County, and State conducted an international design competition to propose alternative visions for the lakefront. The competition winners were well received but no changes were made. A group of local citizens created an organization called the North Harbor Network to push forward some of the ideas from the competition. With assistance from designers from UWM (including myself and Harry Van Oudenallen) an alternative, award-winning, plan was put forward, promoted, and ultimately accepted by the County as the first key step in shelving the freeway plan and creating a large public park and cultural facility

While the initial design, called Lake Terrace, was changed substantially it was revised and renamed as O’Donnell Park in recognition of the leadership of County Executive William O’Donnell. This project was the essential catalyst and proof of concept that created a much larger series of lakefront transformation including the Milwaukee Art Museum expansion, Discovery World, Betty Brinn Children’s Museum, the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial, outdoor gardens, public art, and a much higher-level of public use.

This location on the Milwaukee lakefront still faces challenges to achieve higher levels of coordination and harmony among all the users. Put another way, the downtown lakefront improved immensely once the expanded freeway system was halted but it now faces constraints and opportunities to create a new integrated system for traffic and land use.

Finding A Vision - The First Park East (Reuse Dormant Land)

As part of the initial plan for a freeway system the federal government purchased and cleared land stretching the lakefront to the end of I-194 (referred to at the time as the Park East extension). This land (from Jefferson Street east to Lake Michigan) was completely cleared and sat vacant for many years. The vacant land was “demapped”, taken off the freeway system plan, and placed under local government control. The land further west (from Jefferson Street to I-43) became the subject of the much larger and significant freeway replacement project called “Park East” and discussed in the next section of this case study.

As multiple organizations watched this land lie fallow, a variety of proposals developed in the private sector. Most investors though that townhomes and multifamily housing would never work in the Milwaukee market. The successful proposal from Mandell and Associates, a well respected private development firm, seemed risky to many observers but became a complete success. The picture to the left is an online rendition of their development plan. The photographs below show the housing that was built. Today, anyone who walks in the neighborhood does not see the land use as the remains of a barrier but as a natural, effective, and appealing part of a high-value neighborhood.

The right-of-way for this eastern section of I-194 was cleared, but nothing was built pending the fate of the freeway along the lakefront. When plans for the lakefront freeway were set aside, this land became one of the most valuable downtown opportunities for new development. The opportunities seemed simple but were still controversial. For several years the UWM School of Architecture and Urban planning repeatedly used the vacant land as a basis for studio projects for new housing and neighborhood development. Several faculty members promoted and disseminated the concepts.

One of the local developers, Mandell and Associates, clearly recognized the potential promise of the land and implemented several successful new developments. The full plan used the land for a variety of housing types (townhomes, apartment rentals, condominiums), a retail core, and well-planned parks and garden areas. Most importantly the vacant land was transformed from a barrier (between the downtown and the lower east side) into a harmonious fabric which knitted the different areas together. It also became a model for future development of the demolished I-194 freeway in the next decade.

Unlike the prior study of Park West, and the work on Locust Street, this area was ripe for market-based development. The area was already improving with new, modest residential and retail activity. The downtown decline had stopped, and new investment was imminent. Several different types of housing and retail projects emerged. For most newcomers to Milwaukee there is no obvious separation between the development of the vacant land and the prior development in the surrounding neighborhood. It is a seamless transition. The complete absence of the freeway allowed this land to become a high-value, easily accessible, visually attractive, urban place. This outcome proves that the response to the marketplace may require effective long-term market evaluation rather than short-term “impulses” that respond to the immediate market and conservatively overstate market risk.

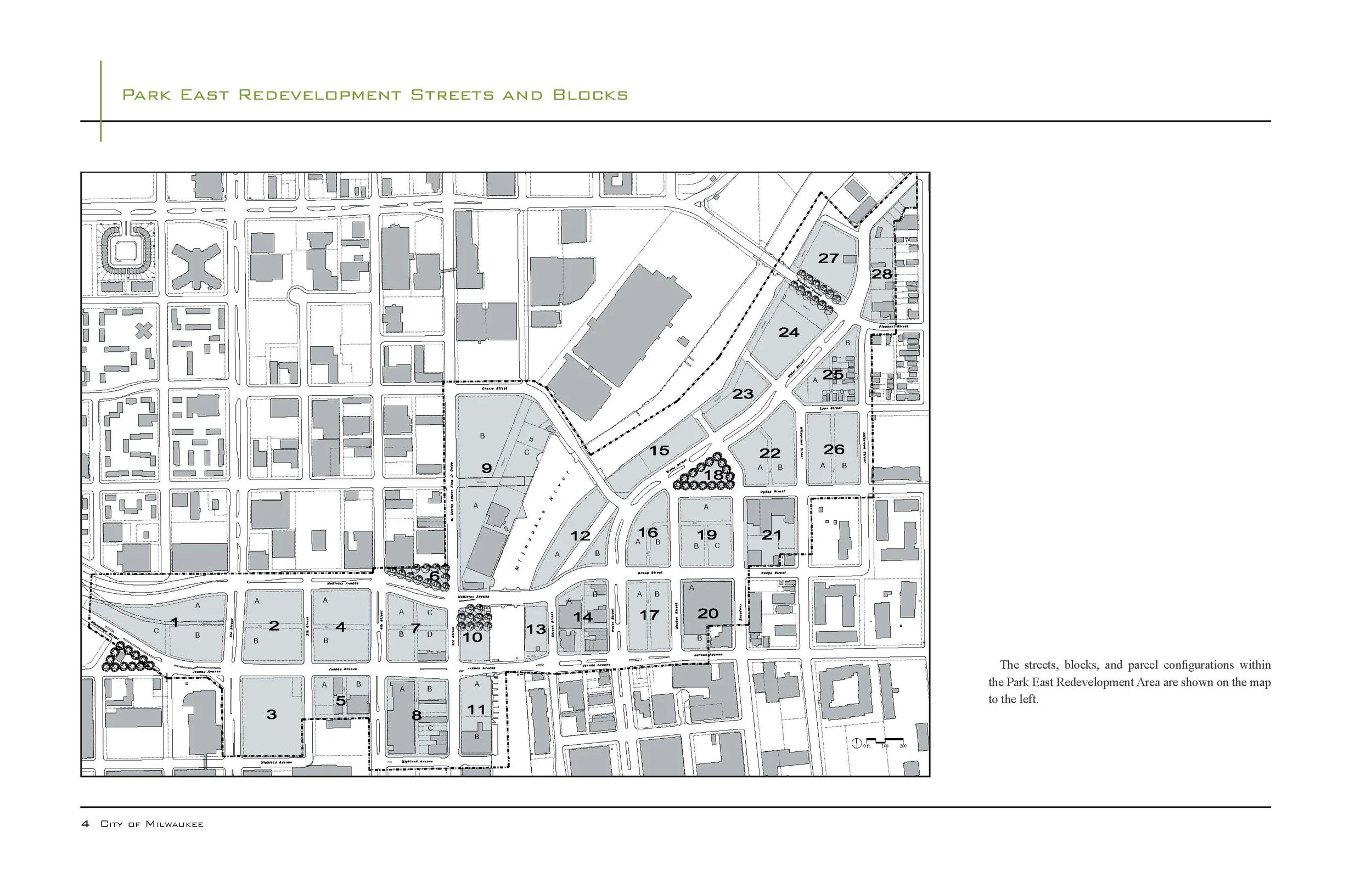

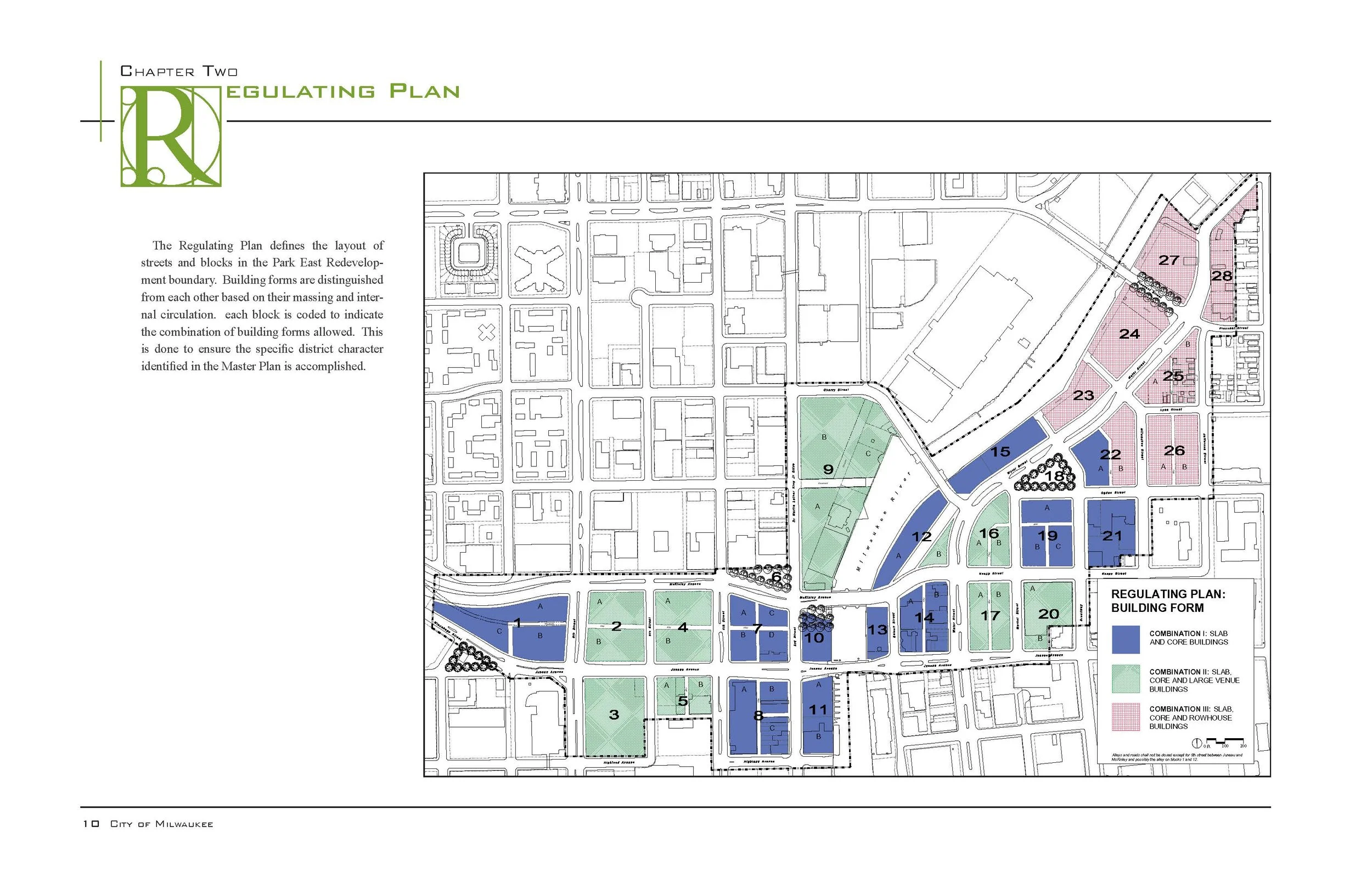

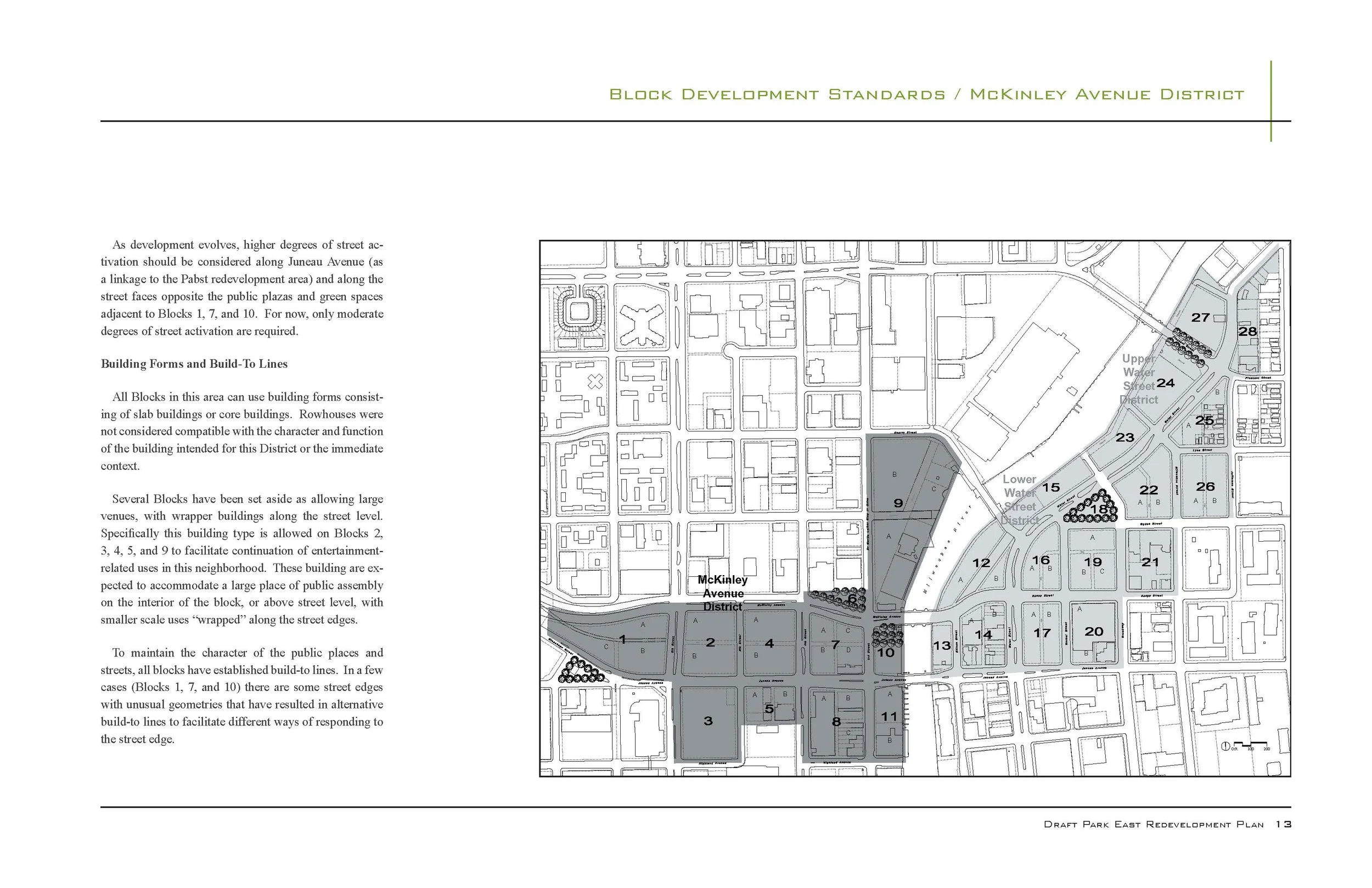

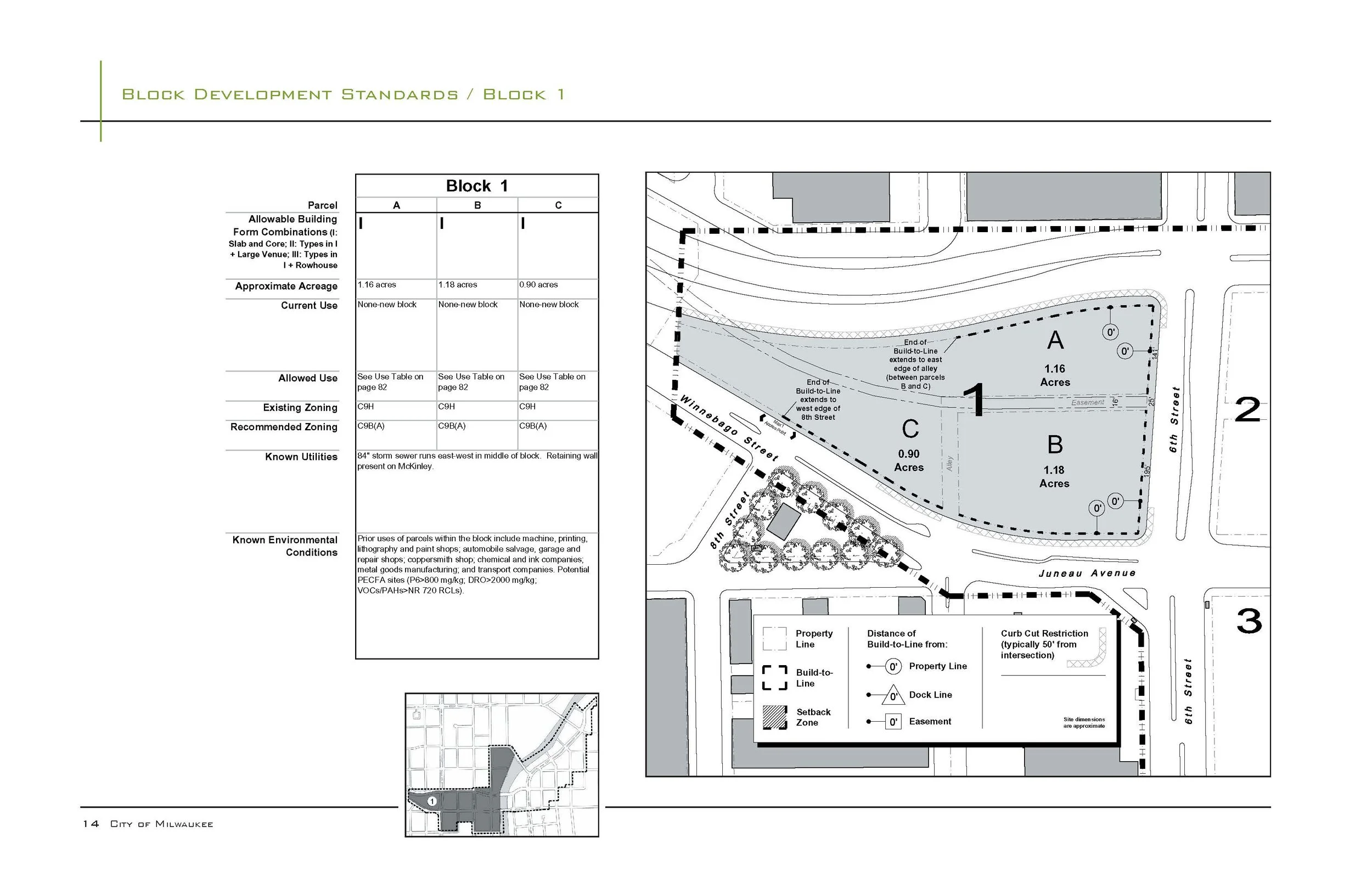

Drive To Future Generations — Remove & Replace The Second Park East

By the year 2000 the strong property market became evident in the downtown adjacent to the freeway (I-194). Nevertheless, the freeway removal and replacement required strong political leadership. Once approved, over 30 blocks became available including both the demapped right-of-way for the Park East corridor in addition to nearby parcels. This became the most complex freeway removal project at the time. The urban planning and design strategy created good urban places through a regulating plan and a form-based code. Components of those documents, mentioned in two other essays on this website, are repeated here.

The author, one of the planners who developed the plans for this project, documented the demolition process. The demolition was, perhaps, too thorough because today, after two decades of continuous successful development, it is almost impossible to envision how powerful this freeway barrier prevented development.

Enormous public opposition arose about the rationality of removing and replacing the freeway with local property development. Here are three of the major position arguments and outcomes to the story:

Opponents predicted that the large volume (40,000 cars per day) would not be able to enter and leave the downtown effectively. In practice McKinley Boulevard handles the 40,000 cars per day which are actually dispersed more easily than the prior freeway.

Opponents stated that new property would never be developed and, if it was, it would not be high value. New development exceeded everyone’s expectations and even produced a surplus of TIF funds used to support other downtown projects.

Once it was clear that development would occur, naysayers said it would take too long -- that is it would take more than a year or two. Immediate short-term redevelopment was never planned nor would it be a good strategy. Redevelopment was planned to occur over a twenty-year time frame so it could be phased and adjusted as needed. It began in 2003, and outlasted the pandemic, the Great Recession, bitter partisan fights, and ultimately achieved a 90% build out by 2023.

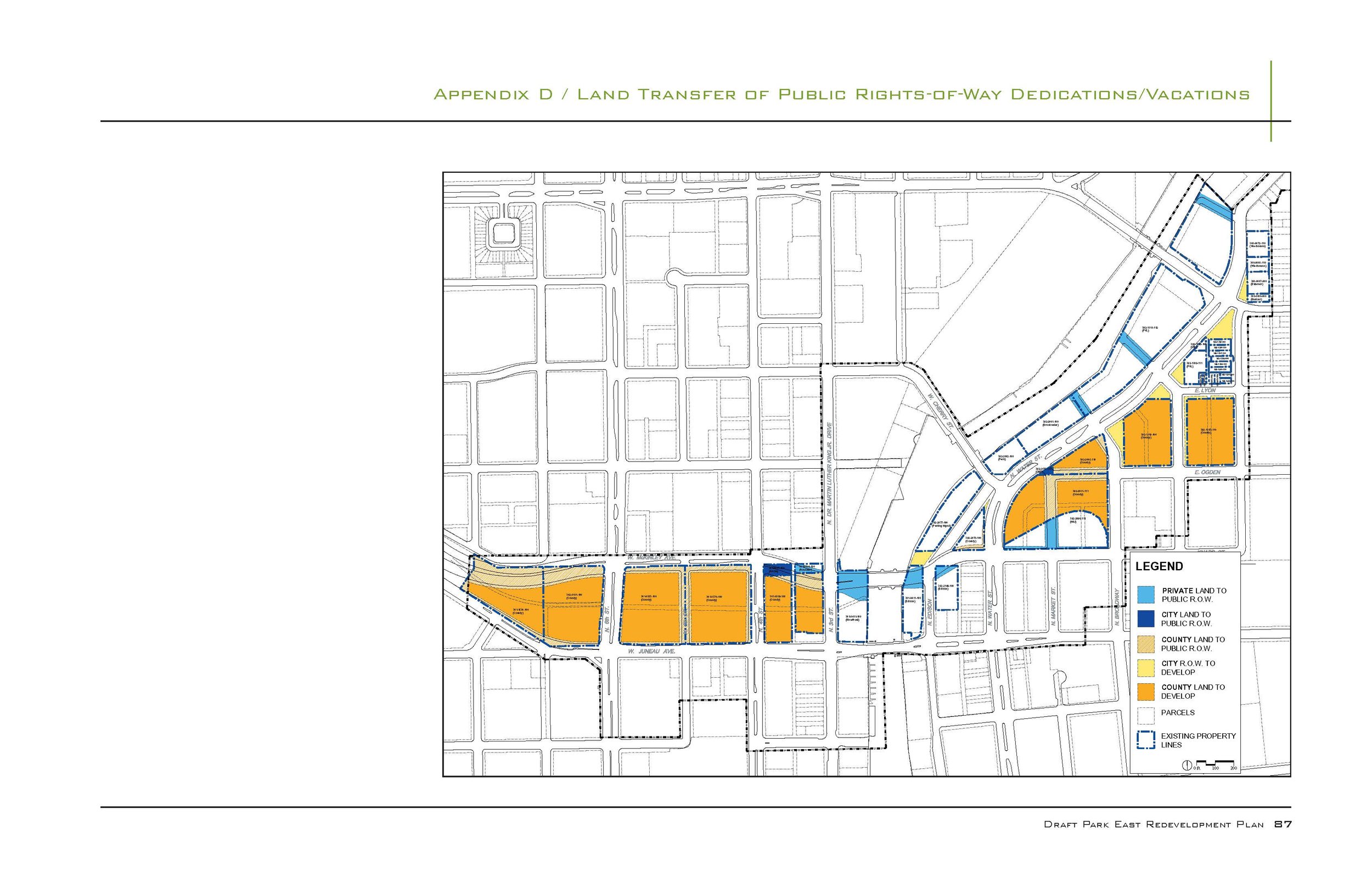

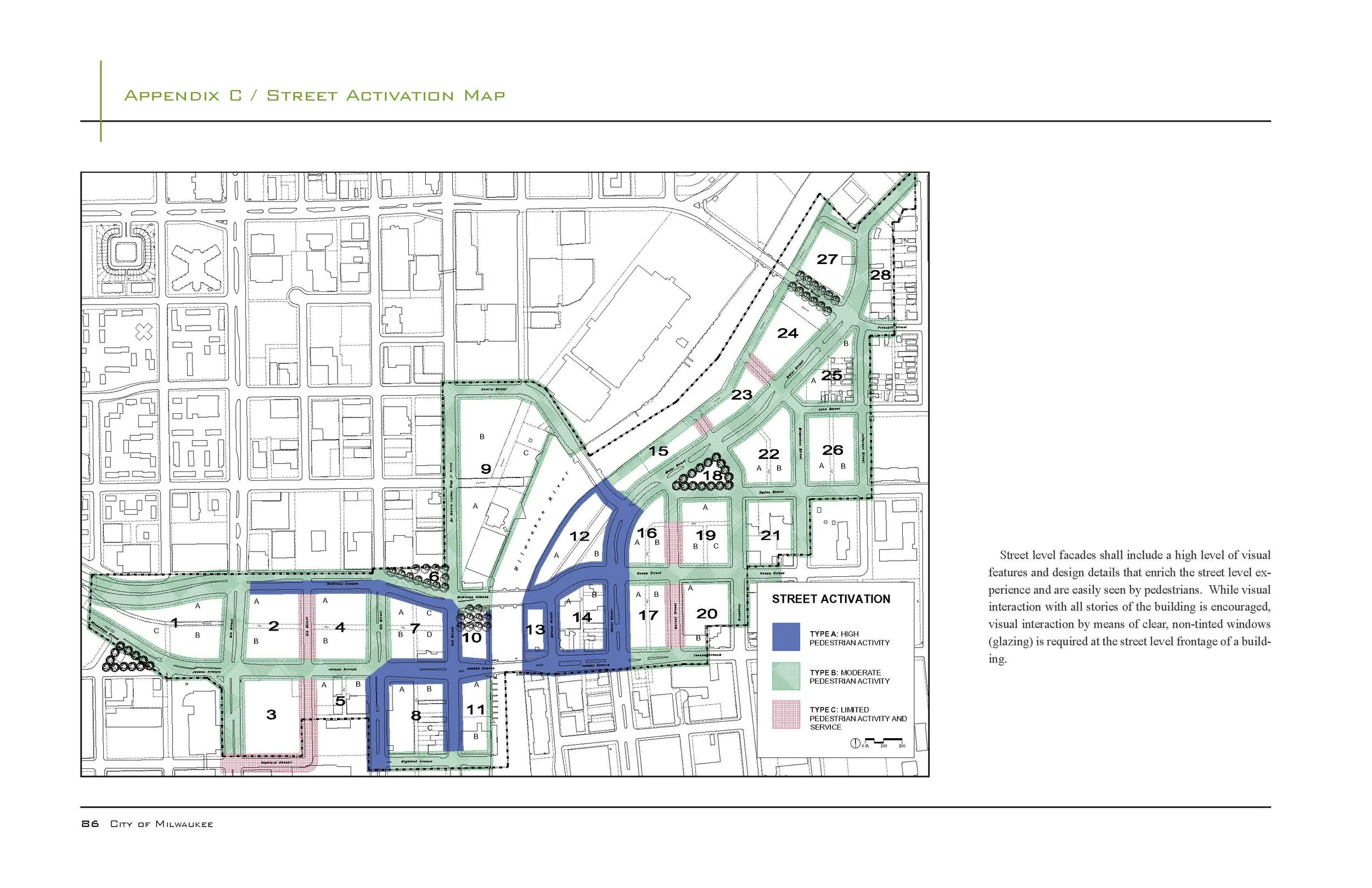

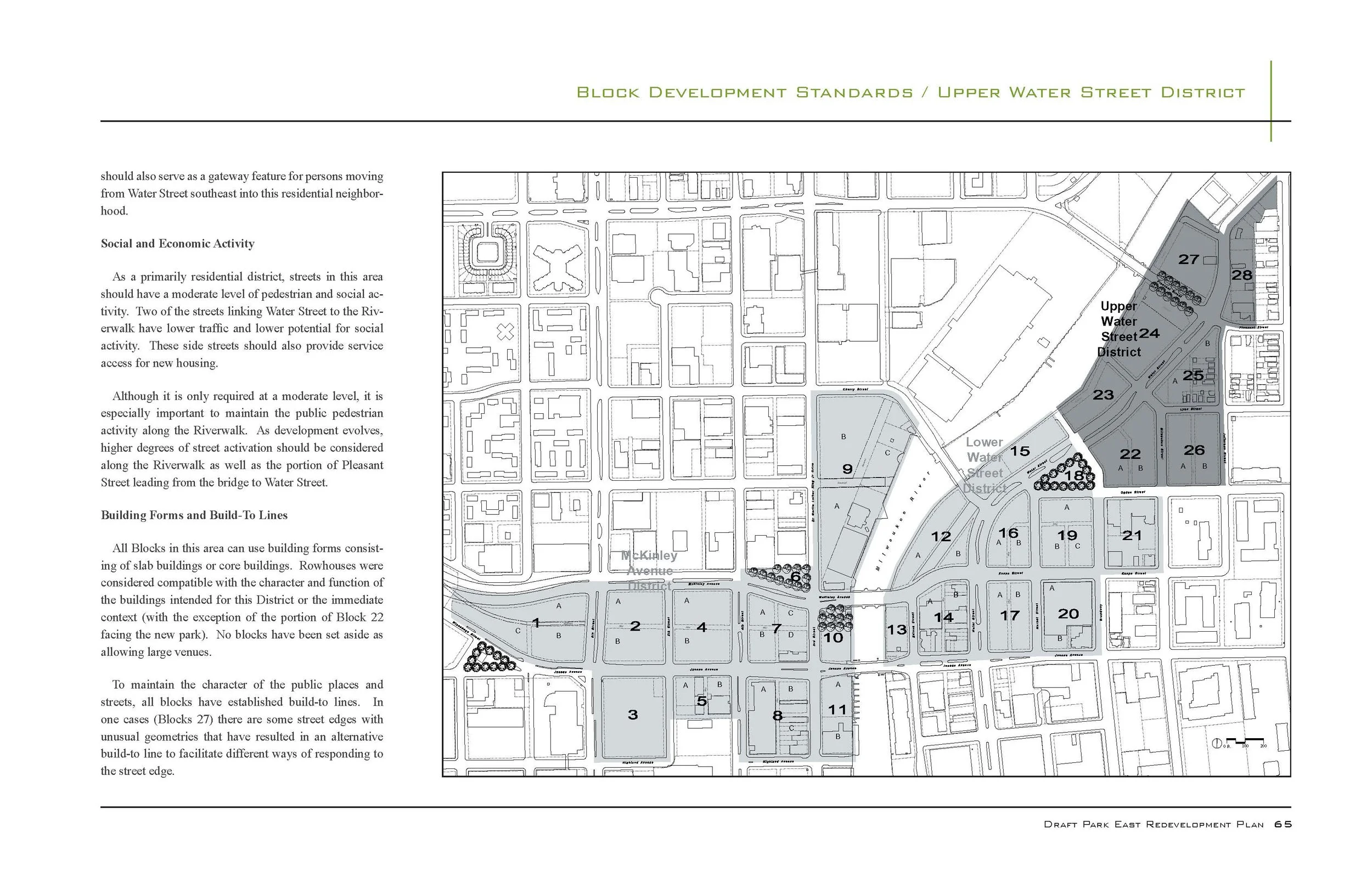

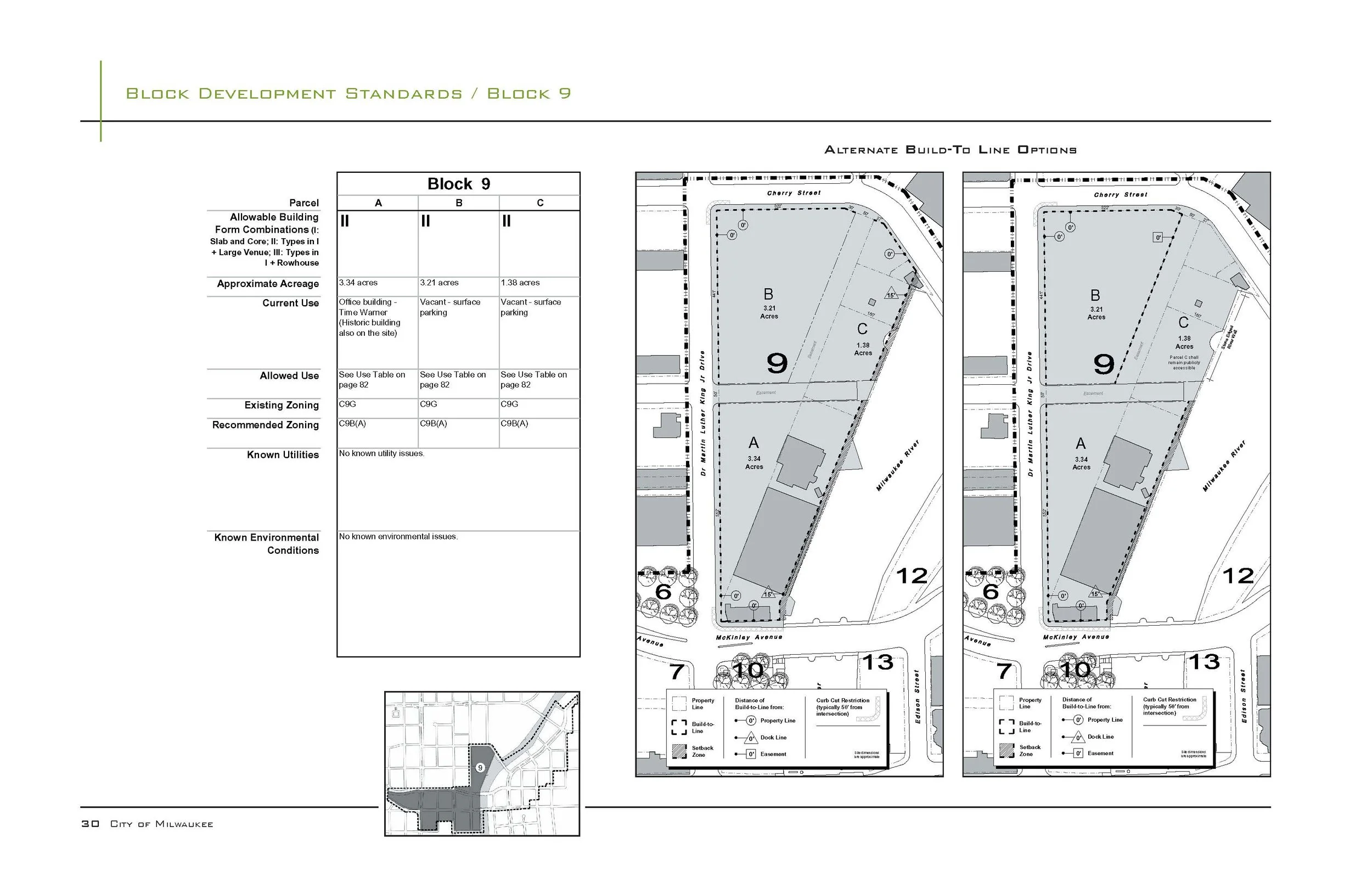

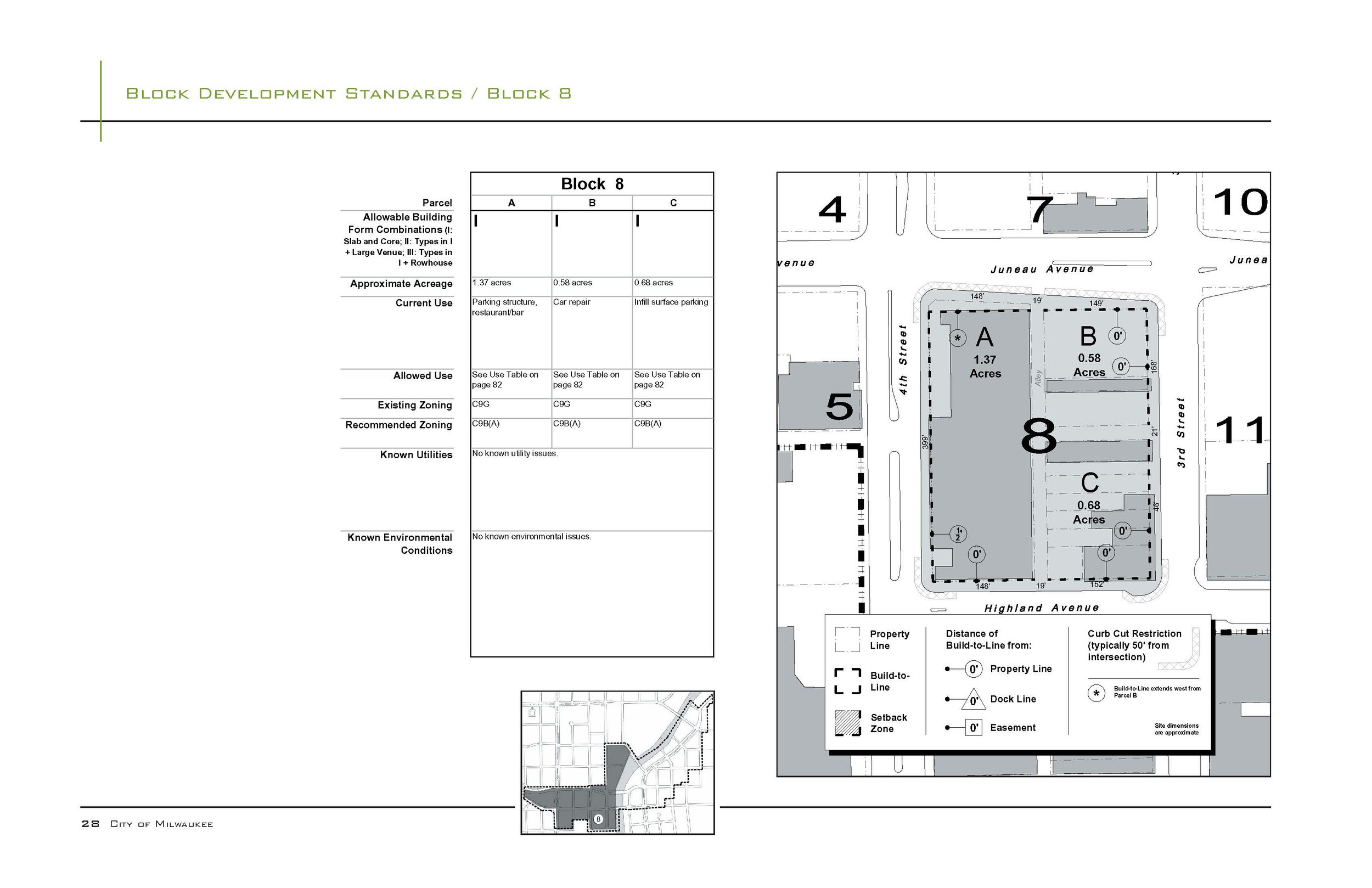

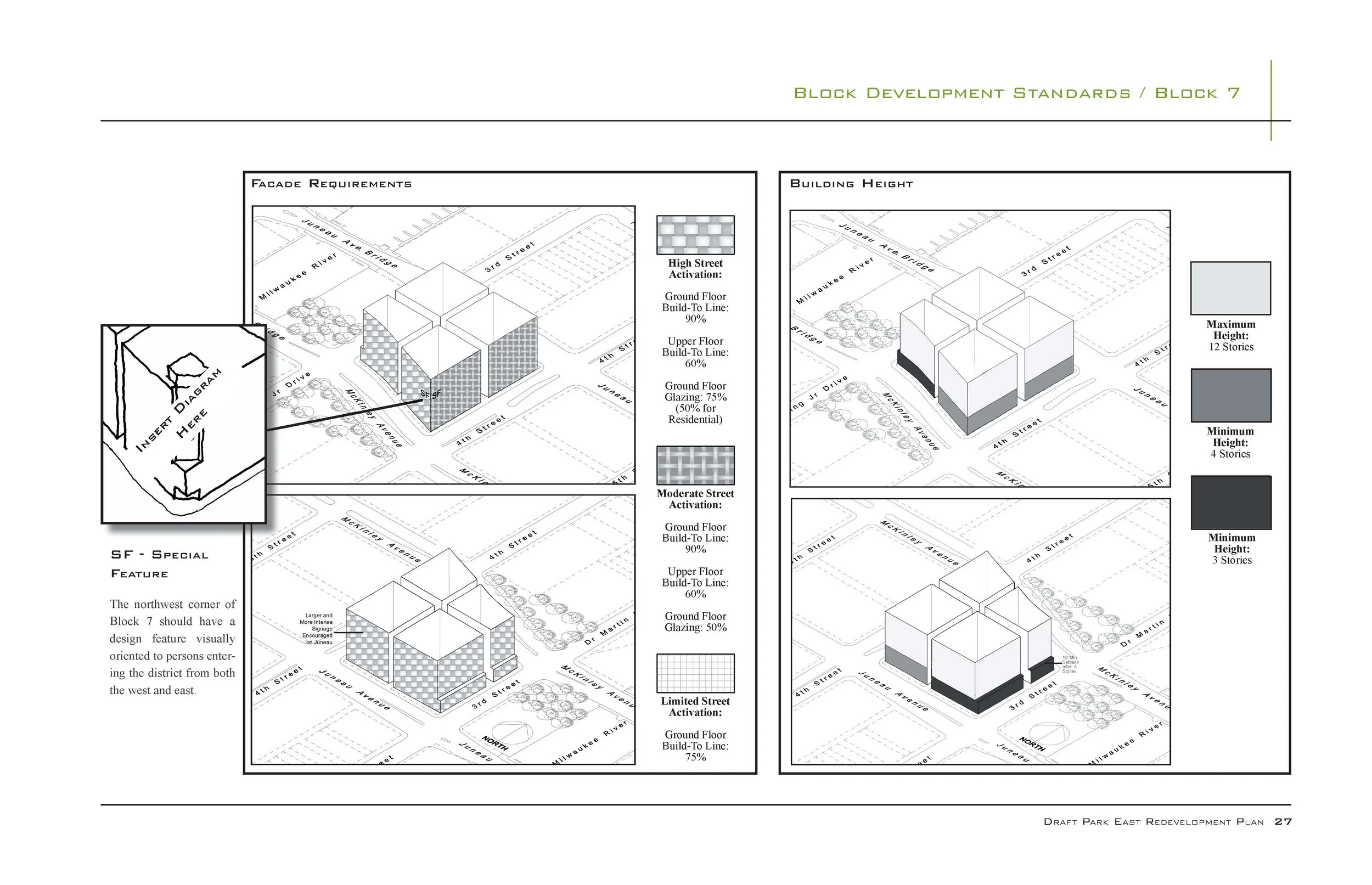

Above: these drawings were developed as the most effective tool for creating a form-based design policy and regulating plan which would guide new redevelopment of buildings and public places. The complexity of the surrounding context, the unique pattern of streets and blocks, and the diversity of neighborhoods led to a block-by-block system of regulation that should be the underlying principle for freeway replacement. The project won a prestigious award from the Congress for the New Urbanism.

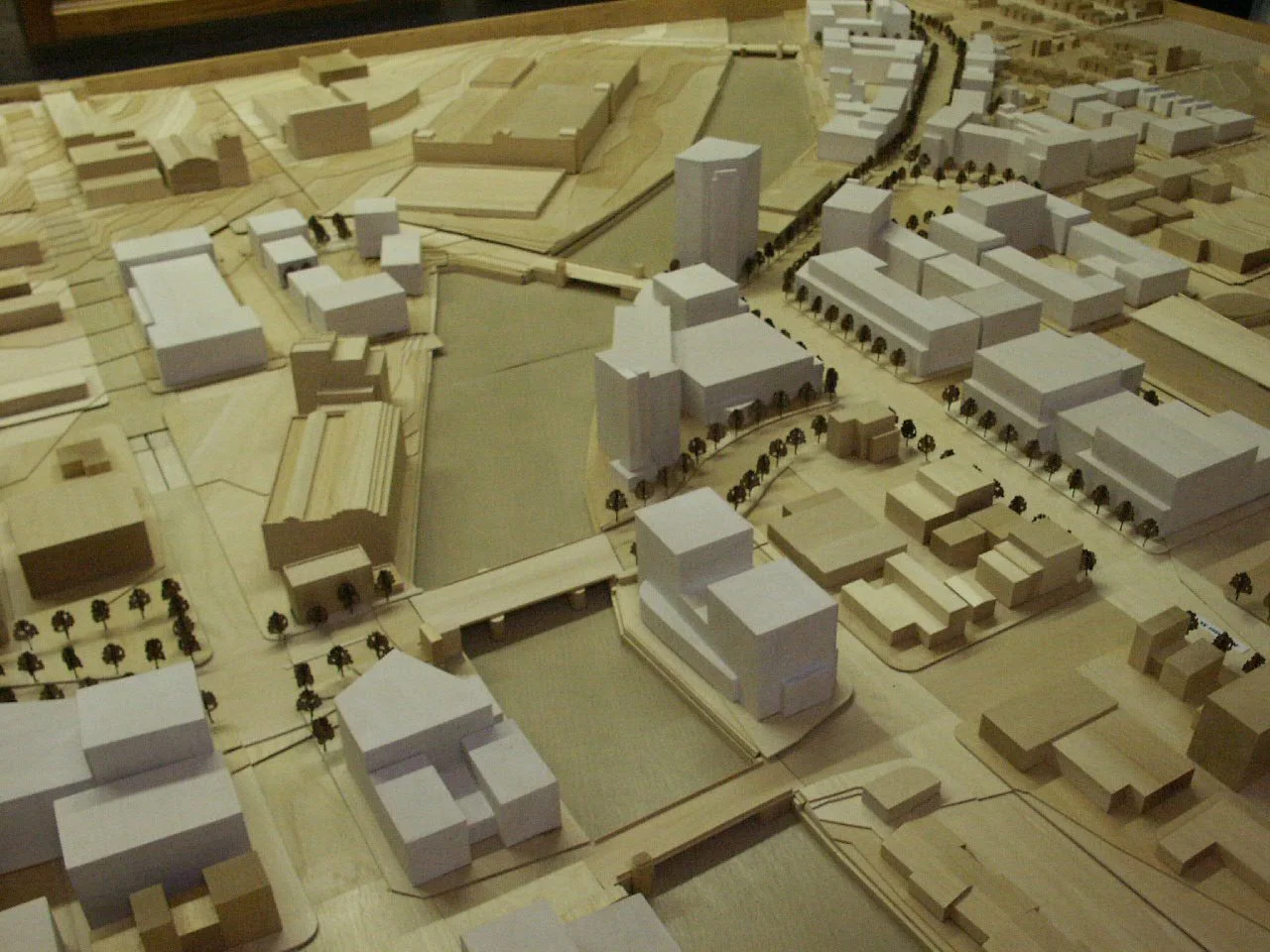

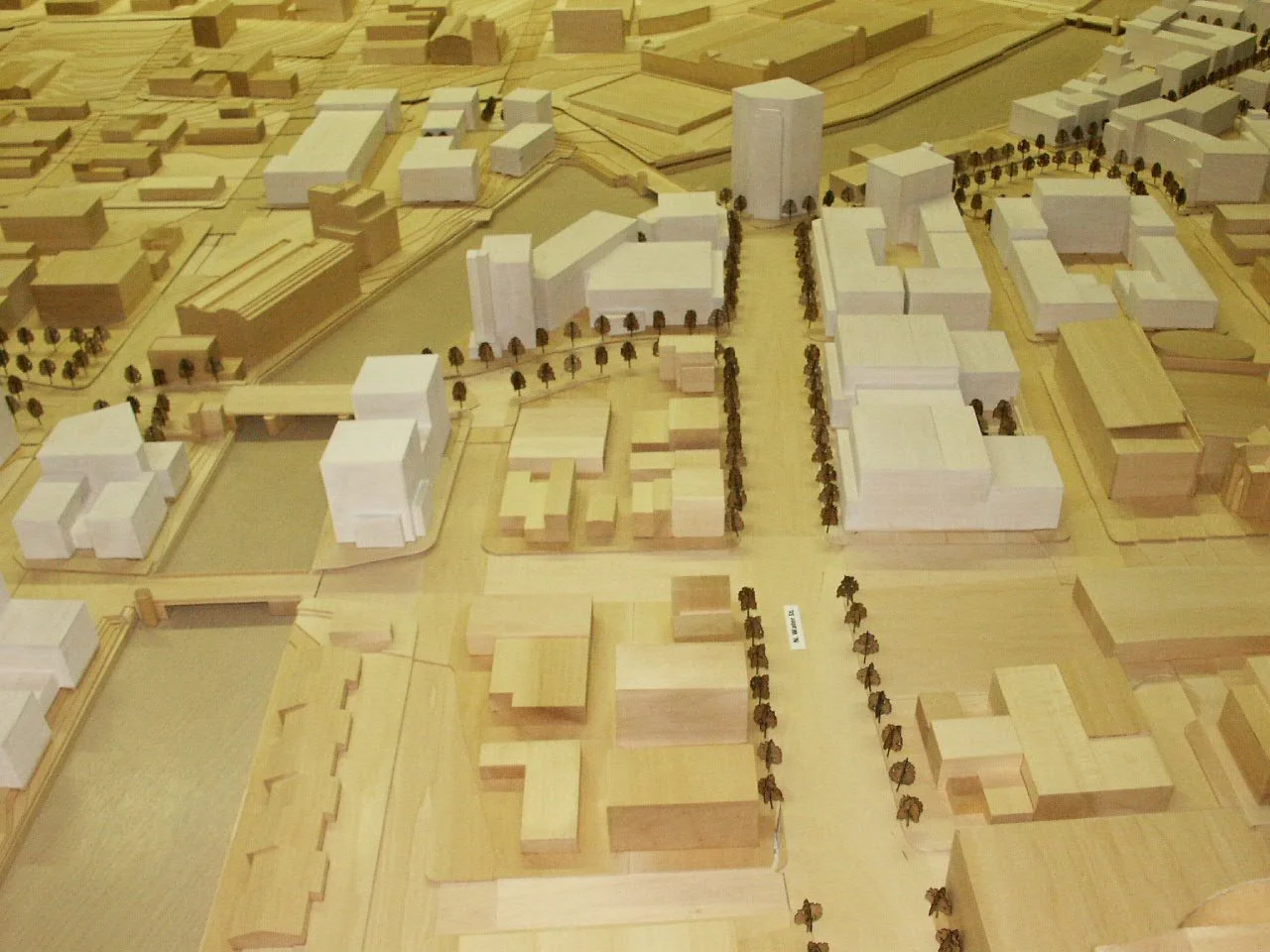

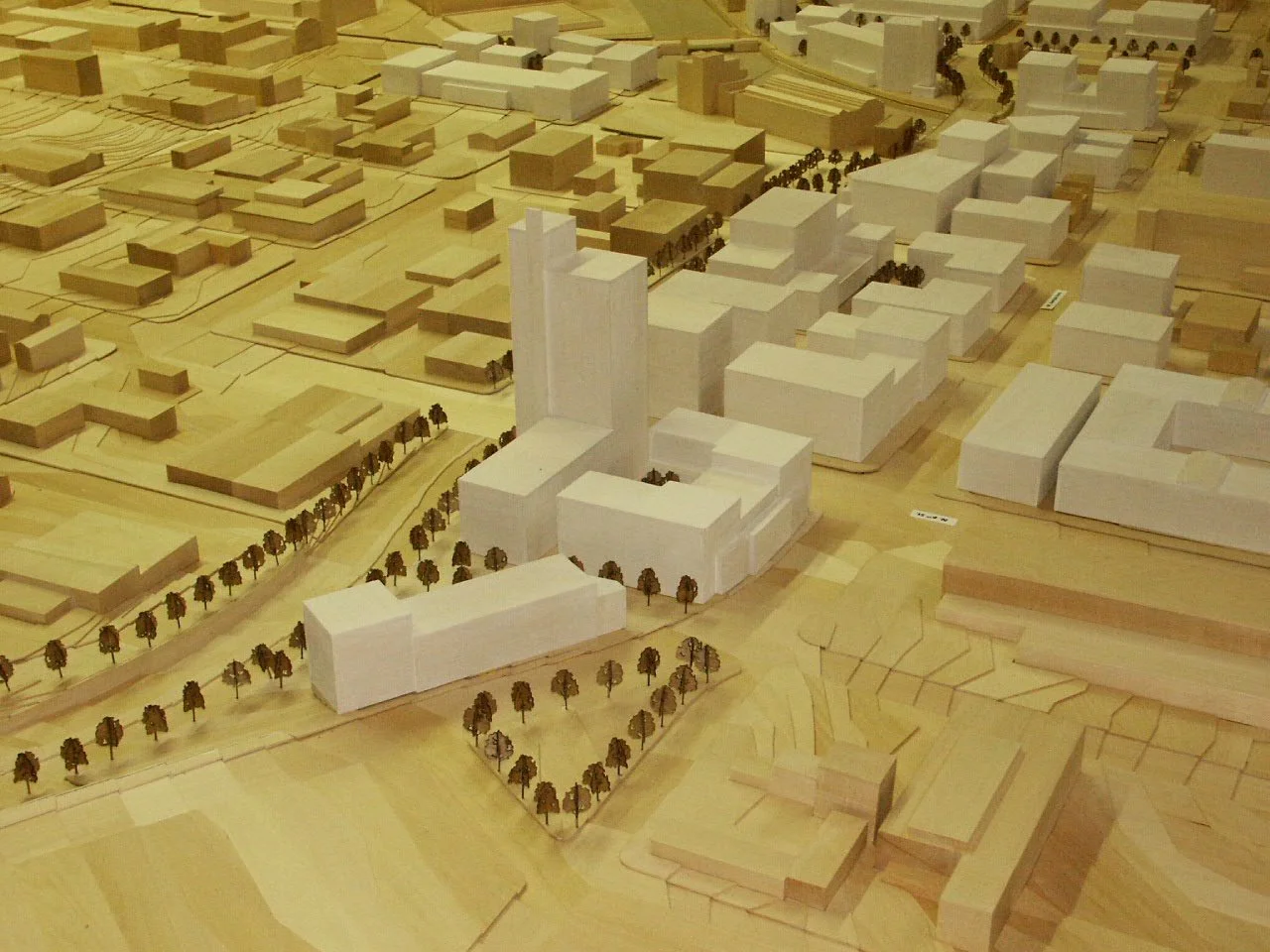

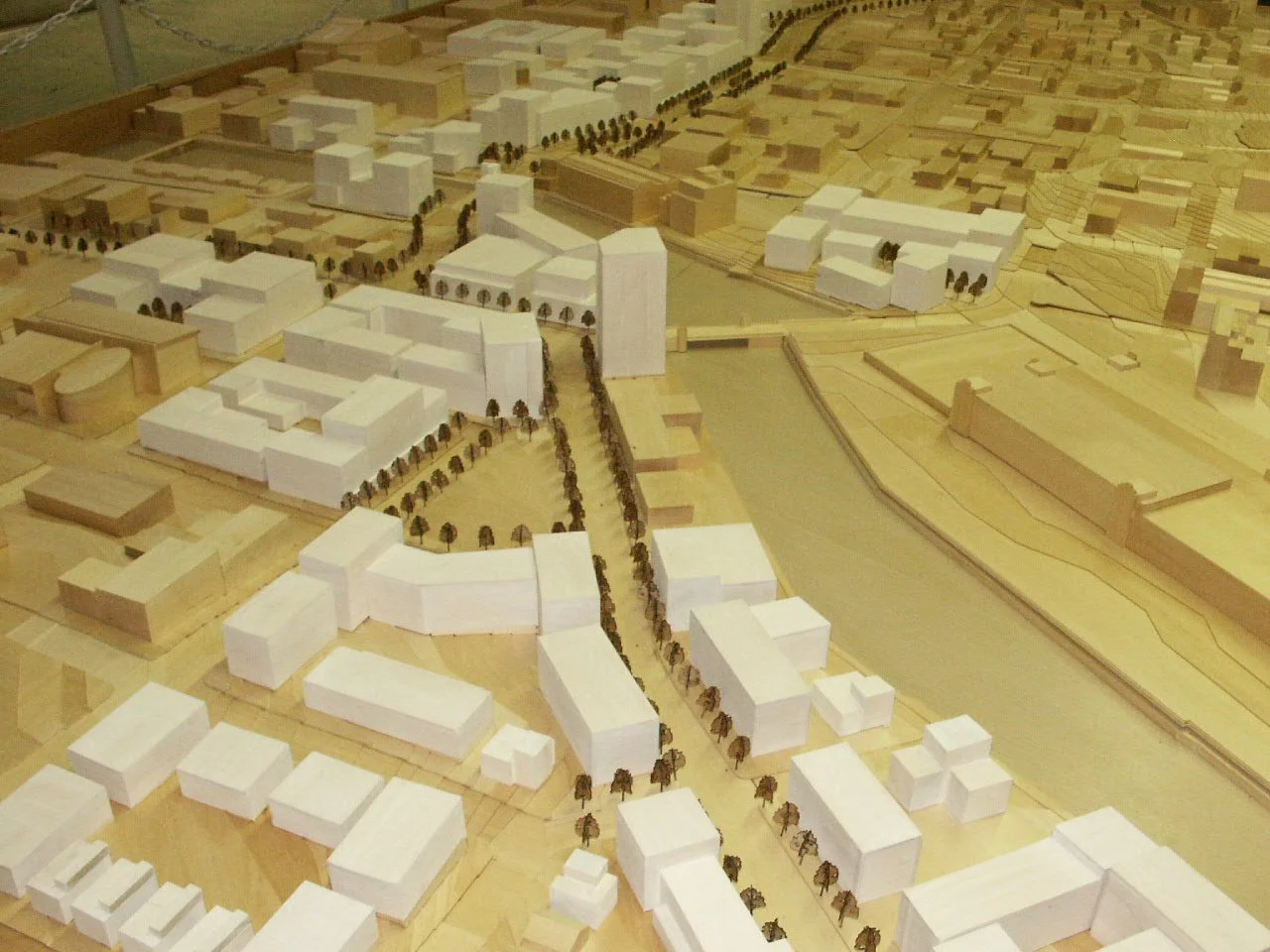

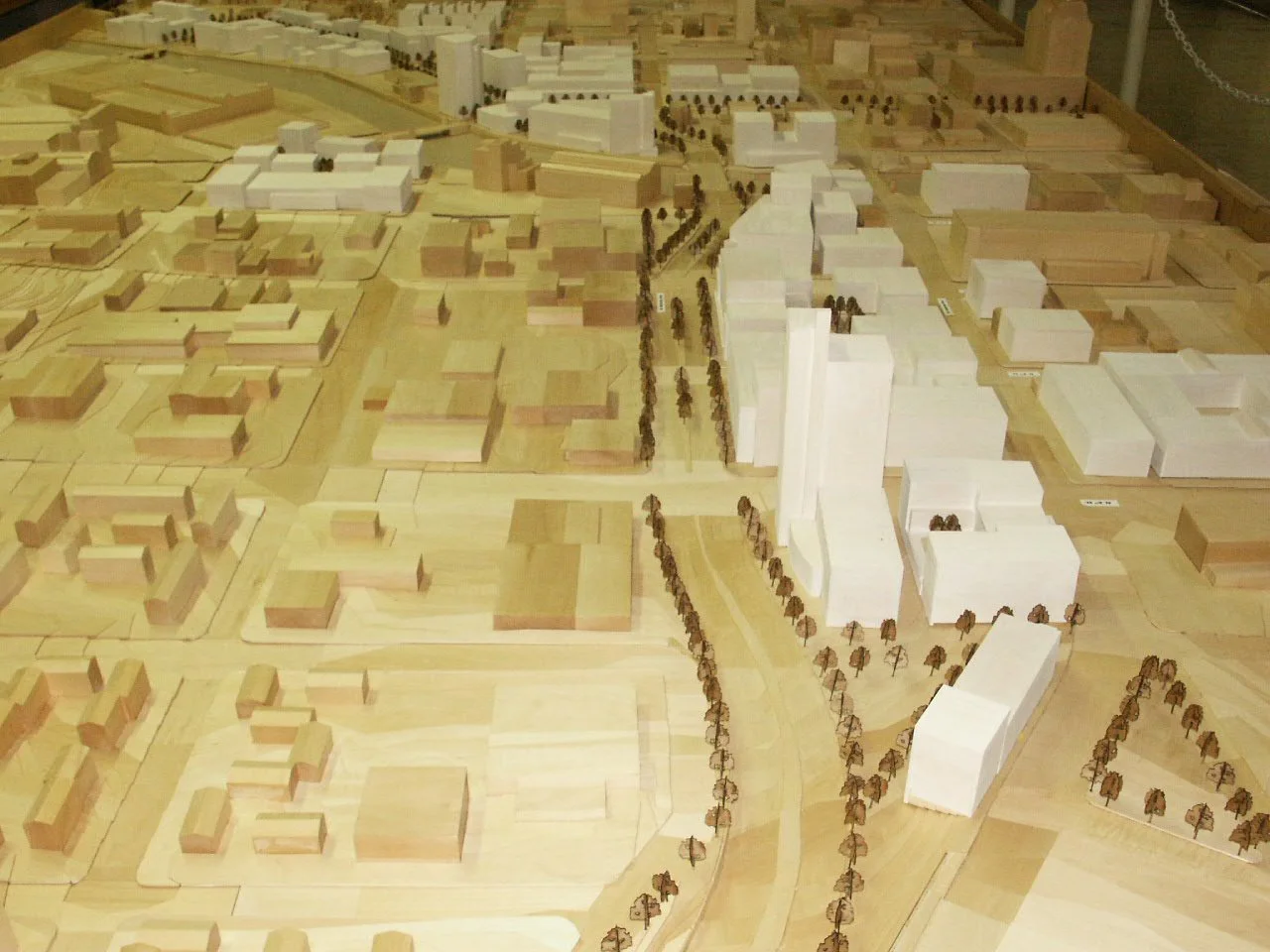

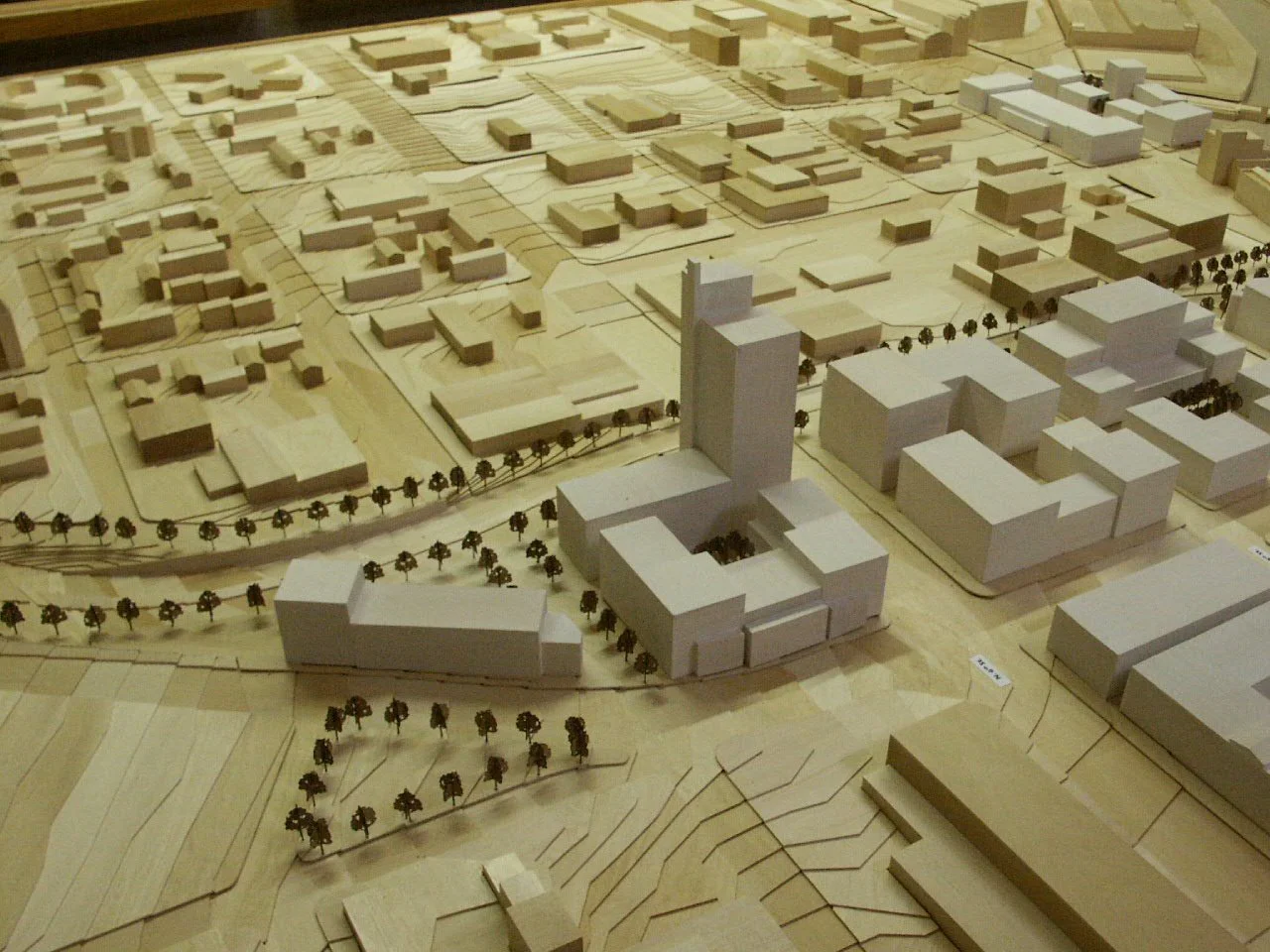

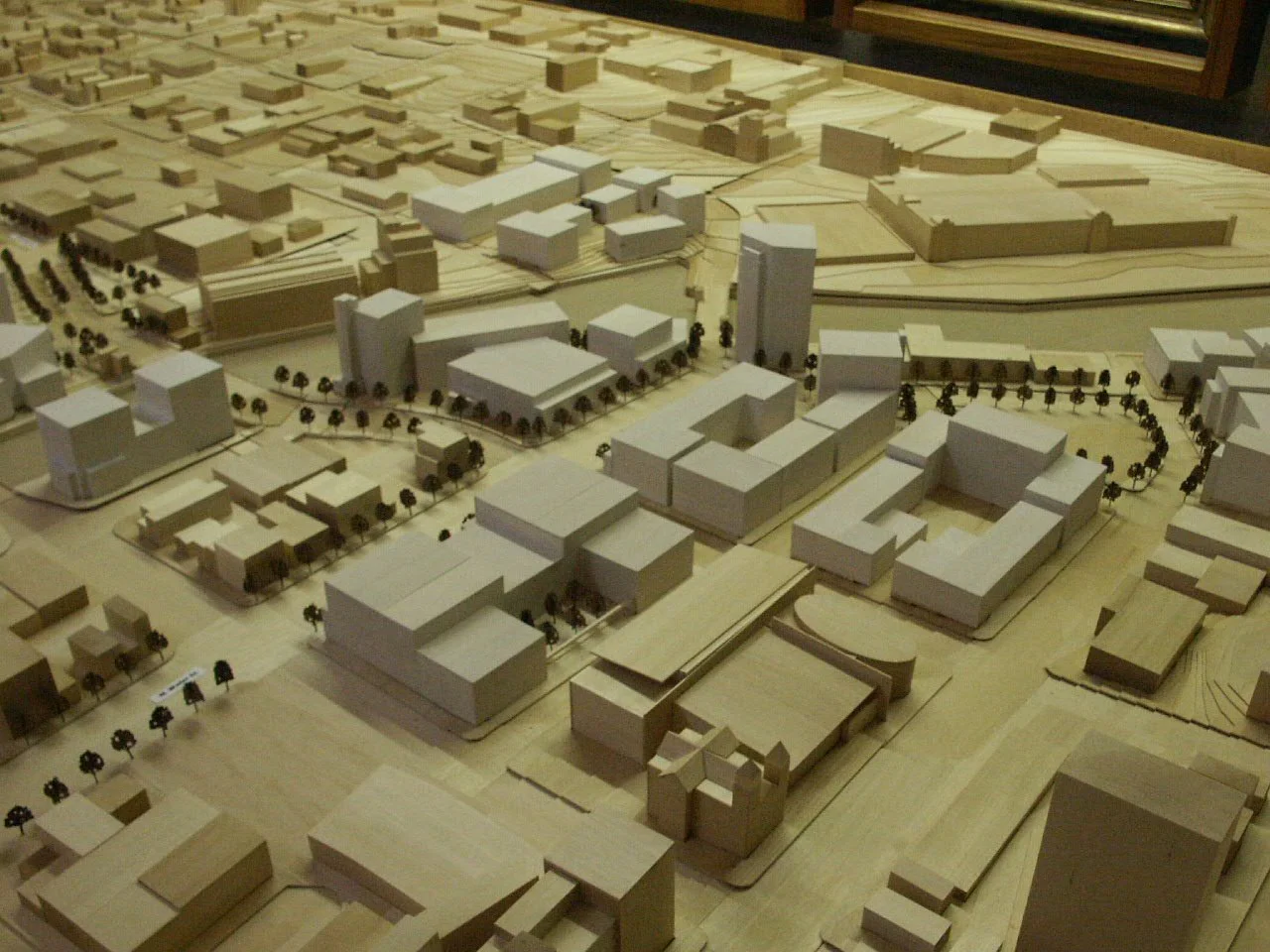

Below: in addition to the technical details in the plan documents the process also included construction of a large scale model depicting multiple options, with variations shown on a block-by-block basis. The model was used to promote the projects, engage the public, and demonstrate the feasibility and appeal of the concepts. Today the model is located in a local museum

Essentially the redevelopment plan required a block-by-block analysis of market potential and capacity. The planning team created and evaluated several street and block plans as well as building a large scale 3-D model to facilitate collective discussion and workshop-style decision making. Here are some key issues in the planning effort.

Accommodate high speed traffic exiting and entering the freeway.

Preserve older historic buildings part of the old brewery neighborhood.

Assume that hillside transitioning will occur later, from downtown to the highly segregated neighborhood to the north

Avoid numerous urban renewal projects that had destroyed much of the historic value.

Make sure the new district that could accommodate the old sports arena.

Promote old and new riverfront buildings on both sides of the Milwaukee River.

Create geometries that fit a mix of both grids and curvilinear streets to accommodate the needed complex street and block geometries.

Incorporate transition areas to the local campus of the Milwaukee School of Engineering.

Harmonize with smaller scale residential housing that was part of the Brady Street neighborhood.

After the plan was adopted, The first project (the Flat Iron apartments) became yet another “proof of concept” and soon other parcels were in planning stages. As noted, the expected twenty-year build-out actually occurred in a slightly shorter time frame. Perhaps the most interesting outcome has been recognition that the poorer, largely black areas north of new development were also impacted positively with reinvestment and value without gentrification.

These two birds-eye photographs from online sources show the Park East project area “before” demolition (on the left) and then, on the right, “after” much of the redevelopment was in process or completed.

Integrate Disjointed Lessons

All of the projects noted above contributed to the detailed learning process for local planning practitioners and designers. The key lesson is that each freeway segment (perhaps every hundred feet of freeway) has a unique neighborhood with different constraints and opportunities for making effective urban places. Unlike engineering design for the freeway itself, which must use standardized design principles (to ensure drivers will have a predictable and safe driving experience) urban places usually require customized dimensions and geometries to fit the undue context of each block and local street. Overall here are some of the critical lessons:

Respect & Respond To The Urban Form Of Streets, Blocks & Buildings

Urban form and geometry grow accretively, over time, to create the street, block, parcel, lot and building forms that become neighborhoods and districts. When planning for revitalized areas around freeways the first step requires evaluating these patterns, historical and contemporary, and understanding the constraints and opportunities for improving urban places. Creating entirely new discontinuous forms does not make places “innovative”. Instead “new” forms, unrelated to their context, usually worsen the barriers and exaggerate separations among places and neighborhoods. With effective talent and skill Innovation, can occur harmoniously, respect and respond to existing urban patterns and avoid making current problems even worse.

Evaluate How Freeways Impact Social And Economic Conditions

As freeways grew and expanded, their surrounding context changed with negative impacts on local demographic, social and economic conditions. Community planners must understand this history, evaluate the relative values of these negative changes and identify conditions that should be diminished, modified, preserved, and/or improved.

Focus On Long-Term Impact, Outlast Markets

Although the plans for addressing neighborhood impacts usually focus on the immediate and short-term outcomes, in practice, plans should focus, instead, on long-term impacts and leverage opportunities for broader positive changes. Market conditions at the time plans are crafted have a major influence on public perception and investor reaction. In practice, however, the neighborhood impacts almost always fluctuate through a longer time frame. The market conditions at the time each of the aforementioned projects began were completely different by the end. None of the final market conditions was projected at the start. If anything, following the initial short-term markets would make problems worse. Consequently, the plans should be designed to fit different long-term market trends over a decade or more (not just in the initial years of post-freeway investment).

Include Leapfrog Opportunities

At first, planners look at neighborhood impacts aimed primarily at the immediate areas surrounding freeways or adjacent parcels. In practice, positive impacts can often leapfrog to nearby, non-adjacent sites. As neighborhood awareness and potential values increase and leapfrog impacts can reach a broader area. The most successful leapfrog impacts respond to specific contextual features.

Engage multiple communities and stakeholders

Every change brings community controversy. Communication strategies based on effective community engagement can change such circumstances into less negative and more valuable and balanced outcomes. While community stakeholders fail to possess the technical knowledge of planners, they usually have valuable historical and cultural knowledge unknown by planners that should be understood and used for decision-making.